With the much-anticipated Sept. 15 Gennady Golovkin-Canelo Alvarez rematch almost upon us, one of the best ways to put the bout into historical perspective is by reviewing the middleweight division’s history since the beginning of the 21st century.

While this span of time has produced no Sugar Ray Robinson, Carlos Monzon or Marvin Hagler, there have been plenty of worthy fighters campaigning at 160 pounds. Here, I’ve compiled a highly subjective list of the top 10. Not everyone will agree with my choices, but that’s half the fun with this sort of article.

When Joe Smith Jr. knocked Bernard Hopkins out of the ring and into retirement on Dec. 17, 2016, it was the end of an era most people didn’t realize was happening until it was halfway over.

There had been a minor genius in our midst all along, grinding away in Philly’s grungiest gyms, an ex-con on a mission that became his destiny. It just took a long time for a lot of folks to catch on.

Hopkins was a prickly, anti-establishment dissident who fought the system and won, the sort of esoteric boxer who carried a copy of Sun Tzu’s “Art of War” in his gym bag.

He was media friendly and loved to talk. But underlying it all was unwavering discipline, cunning intelligence and a mean streak worthy of the street hood he was before incarcerations led to redemption through boxing.

Hopkins made most of his money when he was past his prime, but we’re not concerned with that here. He was at his best as a middleweight. He held a 160-pound title since April 1995 and made 10 successful defenses by the dawn of the new millennium.

He was still a Hagler-esque predator back then, but there were hints of the maddeningly shrewd spoiler that would eventually carry him to unforeseen heights. He said he was saving himself, like his grandmother used to stash jars of preserved peaches on the pantry shelves for future use.

The lid came off a couple of those jars on Sept. 29, 2001, the night Hopkins produced his magnum opus — unifying the world middleweight championship for the first time since Sugar Ray Leonard beat Hagler in 1987, with an 11th-round TKO of Felix Trinidad at Madison Square Garden.

Hopkins took Trinidad apart like a member of a bomb squad disarming an explosive ordnance, first rendering him harmless and then blowing him up at his own convenience. It was one of the greatest performances in middleweight history and certainly the finest of the 21st century.

By the time Jermain Taylor ended his middleweight supremacy in July 2005, Hopkins had tallied 20 successful defenses in a span of roughly 10 years.

Since the turn of the century, no middleweight boxer has accomplished as much as the cantankerous Philadelphian. Most likely that will change at some point over the next 982 years, but for now Hopkins is without equal.

But how do today’s 160-pounders measure up to B-Hop’s legacy? Is a middleweight out there good enough to equal or surpass his accomplishments?

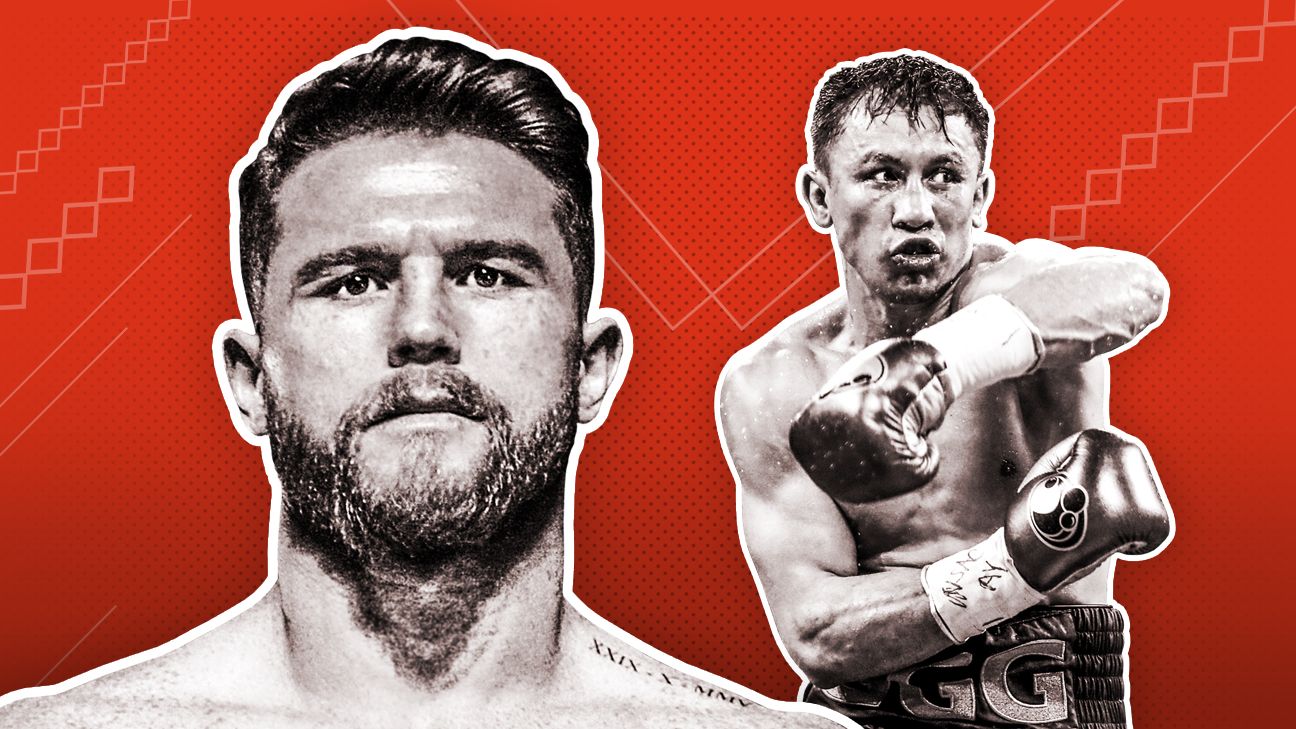

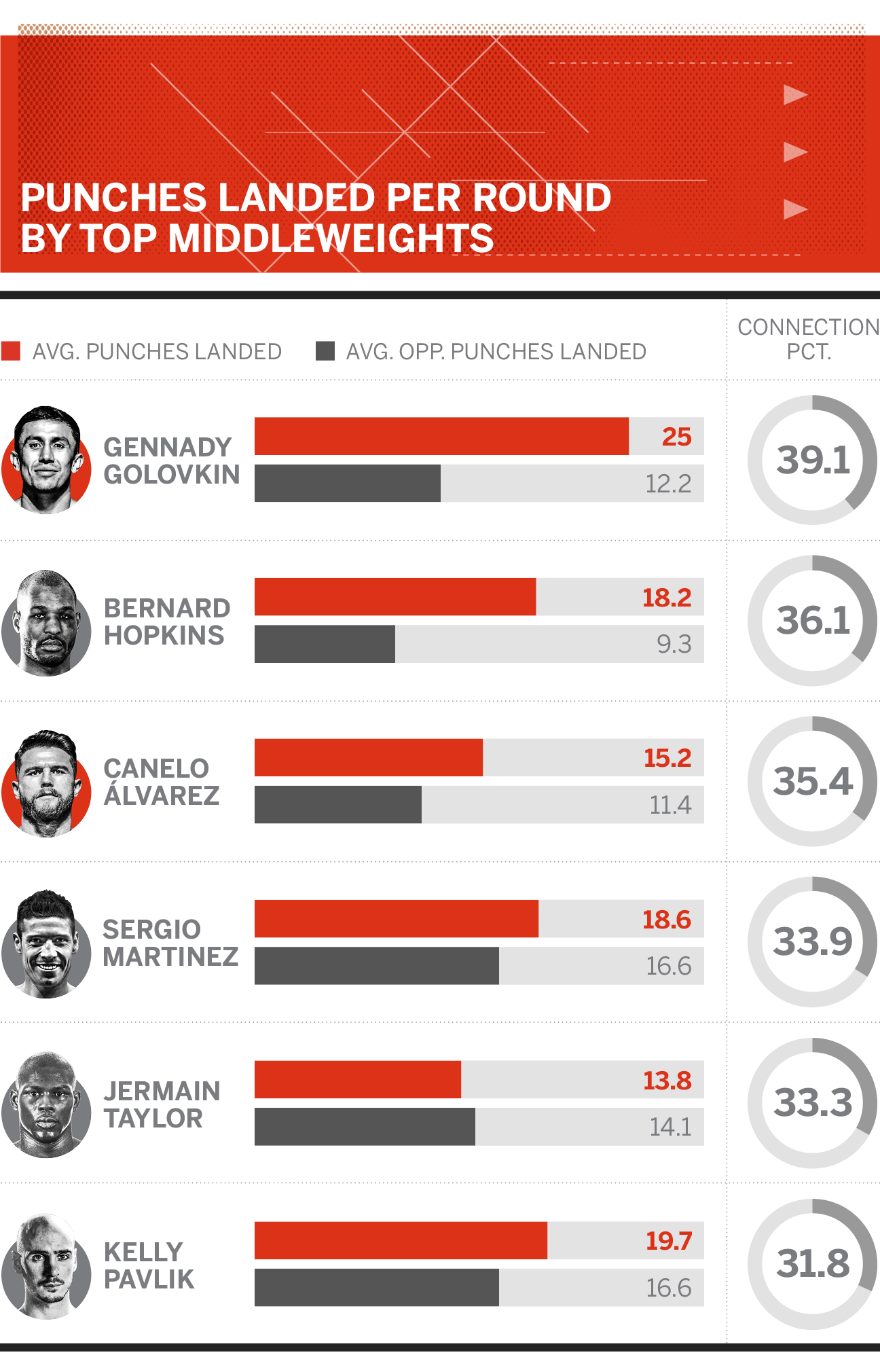

The obvious place to begin the evaluation is with Golovkin and Alvarez.

It didn’t take long for Golovkin to punch his way into the hearts of American fight fans. His popularity grew exponentially with every knockout victory. And his polite demeanor, charming but stilted use of the English language and eagerness to give the public a “Big Drama Show” further enhanced his popularity.

By the time he fought Daniel Jacobs in March 2017, the swift and surgical destroyer from Kazakhstan was No. 1 on most pound-for-pound lists.

Even so, it proved to be a demanding contest for both men, and although he lost a debatable decision, Jacobs exposed the first crack in Golovkin’s invincibility. The Brooklyn boxer was quick, agile and not afraid to trade with an adversary who was riding a 23-bout knockout streak.

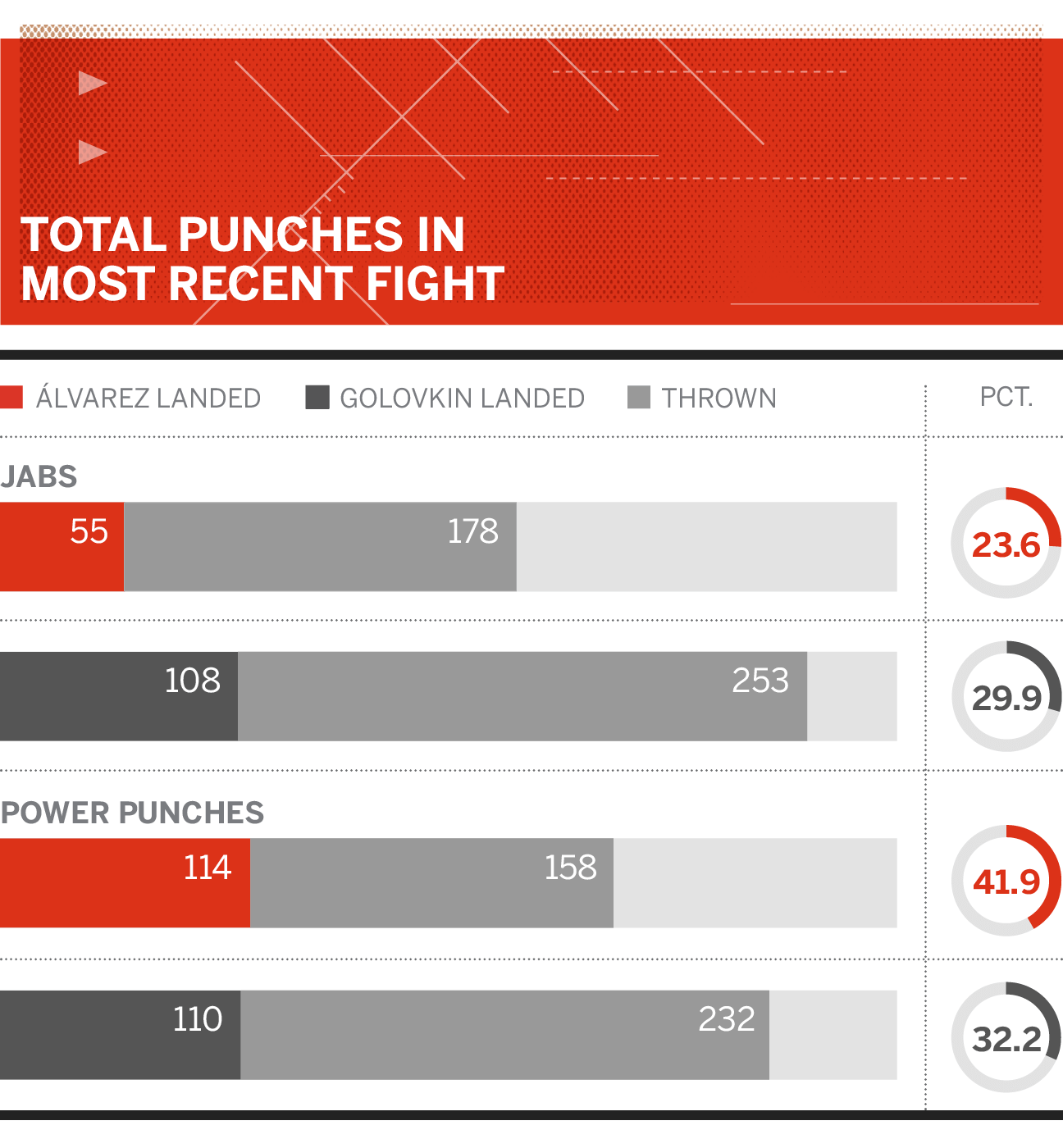

The disagreement over the Jacobs verdict, however, was nothing compared with the stink that followed Golovkin’s draw with Alvarez, who holds the only fragment of the middleweight title “GGG” lacks.

Their September 2017 bout was close but not the anticipated thriller fans expected. Although Golovkin won on most unofficial scorecards, the only legitimate outrage was Adalaide Byrd’s appalling 118-110 score in Alvarez’s favor.

Mexico’s new President-elect Manuel Lopez Obrador won by a record-breaking landslide in the July elections, but if there’s a more popular man in the country, it’s Alvarez.

There were no ballot boxes involved in his rise to superstar status. It was the passionate support of Mexican fans and those of Mexican heritage that made Alvarez boxing’s biggest PPV attraction. They voted with their hearts and wallets.

Although there’s no shortage of critics north of the border, Alvarez is a well-schooled boxer with a solid punch (especially to the body) and a deceptively tight defense. He’s also sublimely relaxed in the ring, a quality hard to quantify but something usually associated with the very best.

His decision loss to Floyd Mayweather in September 2013 didn’t seem to hurt Alvarez’s popularity. After all, fighting Mayweather at that stage of Alvarez’s career was a risky move, which brings us to a factor that weighs heavily in his favor: He’s fought a lot of good fighters, including Miguel Cotto, Erislandy Lara, Amir Khan, James Kirkland, Liam Smith, Josesito Lopez, Austin Trout, Julio Cesar Chavez Jr. and Shane Mosley.

Not all of them were in their prime when Alvarez fought them, but some were and others close to it. Any way you look at it, it’s an impressive résumé.

The scheduled May 5 Golovkin-Alvarez rematch was scuttled when Alvarez tested positive for the banned substance clenbuterol. Providing there is no controversy when they try again Sept. 15 at the T-Mobile Arena in Las Vegas, the winner will be heir apparent to Hopkins’ middleweight preeminence.

Jacobs, meanwhile, seems to be the odd man out. He certainly deserved a rematch with Golovkin. But in boxing, money and politics often override merit. He’s fought twice since, beating Luis Arias and Maciej Sulecki, a pair of previously undefeated foes who built their glossy records against modest opposition.

Sergio Martinez had a brief but brilliant run at the top and then he was gone, betrayed by a twist of fate and an aging body.

“Maravilla” was already 35 and a veteran of 48 professional fights when he won the middleweight championship with a unanimous decision over Kelly Pavlik in 2010. But the Argentinian southpaw with the matinee-idol looks fought like a man 10 years younger.

That opinion was reinforced in his first defense when he tallied a sensational one-punch knockout of Paul Williams that left the touted challenger out cold, face down on the canvas. An additional trio of knockout defenses boosted Martinez’s reputation and pushed him up the mythical pound-for-pound ratings.

Everything changed when the unbeaten but much-maligned Julio Cesar Chavez Jr. dropped Martinez in the closing moments of a title fight in September 2012. The champion regained his feet and lasted until the fight-ending bell, winning a unanimous decision.

It was the beginning of the end. Martinez badly injured his right knee as he fell, and despite surgery he was never again the same fighter. In his final two fights, Martinez looked like a marionette with sagging strings.

Miguel Cotto, in the midst of the Indian summer of his career, took the title on June 7, 2014, knocking down gimpy Martinez four times before it was stopped six seconds into the 10th round.

It was “Maravilla’s” 56th and final fight. Before his injury, he would have been highly competitive against any of his contemporaries, including Golovkin and Alvarez

Pavlik was one of those “if-only” fighters who had a good career but not as good as it could have been — if only he hadn’t had an alcohol problem.

Plenty of fighters have outside-of-the-ring issues — some overcome them and others do not. Pavlik was one of the latter. It was a shame. The guy could fight and sold a lot of tickets.

An entertaining TKO of lethal-punching Edison Miranda earned him a title shot against Jermain Taylor in May 2007 in Atlantic City, and Pavlik took full advantage of the opportunity.

With a large and noisy contingent of hometown fans from Youngstown, Ohio, cheering him on, Pavlik pummeled the favored Taylor into a seventh-round TKO defeat.

A more difficult but convincing unanimous decision over Taylor in a rematch quieted most remaining skeptics, and a bright future seemed assured.

Following two easy defenses, Pavlik and his team made a colossal mistake — they agreed to fight Hopkins in a non-title catch-weight bout. Hopkins gave him a prolonged and painful beating, the sort that can ruin a fighter, and all indications suggest that’s exactly what happened. If not in body, then surely in spirit.

Four fights after losing to Martinez, Pavlik was done, still struggling with the demons that made him a what-if fighter.

Bronze medalist Taylor came home from the 2000 Olympics in Sydney, Australia, a highly sought-after prospect. He breezed through the usual collection of journeymen and fringe contenders on his climb to the top, and on July 16, 2005, he beat Hopkins via split decision to win the world championship.

The fight was close and in the eyes of many Hopkins deserved the verdict, but when Taylor outpointed him more convincingly later the same year, the personable young man from Little Rock, Arkansas, seemed set for a lengthy stay atop the division. But it wasn’t to be.

His second victory over Hopkins turned out to be the finest victory of Taylor’s career. When the best he could manage in his second defense was a draw with Winky Wright, it wasn’t cause for too much alarm. After all, the left-handed Wright was a consummate technician with an excellent defense.

But when undersized Kassim Ouma gave him a tougher-than-anticipated fight and light-punching Corey Spinks held him to a split decision in Taylor’s third and fourth defenses, some of the luster began to fade.

When Pavlik stopped him in September 2007 to win the title and then beat him again by decision, Taylor’s problems were explained away as a need to move up to super middleweight. But when he was knocked out in two of his first three bouts in the 168-pound class, he was done as a world-class boxer.

Today, Taylor grapples with neurological issues, most likely the consequence of his boxing career, which have resulted in erratic behavior, violence and incarceration.

Despite going undefeated in 26 bouts and winning a middleweight title since he turned pro in February 2009, Britain’s Billy Joe Saunders remains an enigma.

A southpaw with superb boxing skills, his performances have been uneven to say the least. He boxed brilliantly in his most recent bout, virtually shutting out Canadian puncher David Lemieux in December 2017. Previous title defenses against Willie Monroe Jr. and Artur Akavov, on the other hand, were excruciatingly boring.

Saunders has also postponed or withdrawn from fights claiming injury or illness on a fairly regular basis. Most recently, English rival Martin Murray accused him of faking an injury to avoid boxing him.

Saunders has fought only three times since beating Andy Lee for a title in December 2015, and seems almost ambivalent about his boxing career. He clearly has the talent to accomplish much more than he has so far, but talent alone is seldom enough.

Arthur Abraham is built like one of the columns holding up the Brandenburg Gate and fights with his gloves held high in front of his face. It’s a style that affords little in the way of a target as he inches his way forward, looking for an opportunity to land a telling blow of his own.

Outside of Germany, Abraham is considered a protected fighter who has seldom strayed outside of his adopted home of Germany. To an extent the critique is accurate. He’s fought mainly in Deutschland, often against weak opposition in front of friendly judges.

Nevertheless, he won a vacant middleweight title in 2005 and made 10 successful defenses. He also did a fair amount of good work that should be acknowledged. Among the victims during his middleweight years were Sebastien Demers, Raul Marquez, Ikeke Kingsley and Miranda.

That the 38-year-old Abraham is still fighting is a testament to his resiliency and enduring popularity in Germany.

Had the first 18 years of the new century been blessed with an abundance of middleweight talent, Jermall Charlo would not have made the list. After all, only two of his 27 pro fights have been in the 160-pound weight class. But after scouring candidates with more middleweight experience, Charlo gets the final spot on the basis of potential.

Consideration was given to Felix Trinidad, but “Tito” had only six middleweight fights and lost three of them. Same deal with Wright. Just six of his 58 bouts were at middleweight — three wins, two losses and a draw.

Conversely, Charlo is a gifted boxer in position to enlarge his thin middleweight résumé. He has yet to fight any of today’s middleweight elite and could be a flash in the pan. But based on his current form, that seems unlikely.