What makes NASCAR significantly different than all other sports is that it loses its franchises forever.

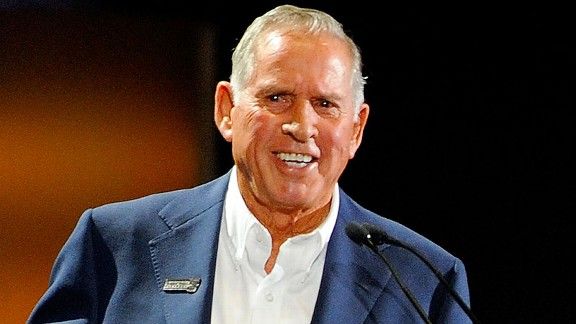

On Monday, we lost David Pearson, a racer many NASCAR historians consider the purest and greatest driver in the sport’s history.

Pearson accumulated 105 wins, second only to Richard Petty (200) — his primary rival.

That rivalry was no different than what I experienced during my childhood between the Dallas Cowboys and the Pittsburgh Steelers or the Boston Celtics and Los Angeles Lakers. You couldn’t be a fan of both, but a big difference between Petty and Pearson and the aforementioned teams was that you could root for one without despising the other.

Pearson won races at the toughest of racetracks against the toughest of drivers. The greatest example included Pearson’s domination of a track that most would suggest couldn’t be dominated. Pearson won 11 times at Darlington (S.C.) Raceway, the track nicknamed “Too Tough to Tame” because of its propensity to abuse drivers who dared to think they had any control of her (her because the track eventually became known as the “Lady in Black”).

There was no track on the circuit more challenging then the one that shared the same home state as the Silver Fox. No driver ever tamed Darlinton as often as Pearson did — not Earnhardt, Gordon or Petty.

In 1993, Pearson was kind enough to help me transition to driving a stock car at Darlington, which was a track like no other I had ever seen. I had no reference and I was lost. Pearson took me around the track, stopping several times and directing me as to what I should be doing with my feet in the car.

We rolled around the track slowly with the three-time champion at the wheel of a van owned by my PR director, Ron Miller. Pearson stopped the van in what used to be Turn 1 and suggested I should be out of the accelerator at this point. I looked at him respectfully and accepted his advice skeptically. I then thought to myself, as the van began rolling again, this is not going to work because it’s five car lengths too soon.

We moved a couple of hundred feet forward in the van and he said, “Here is where I want you to go back to the gas.”

For the second time I said something, but this time out loud: “Here? It seemed 10 car lengths too soon!”

Pearson replied: “Do it really, really easily, just barely open the butterflies on the carburetor — don’t you make those rear tires angry.”

I then asked the greatest driver ever: When making a lap at Darlington Raceway, when should I be full throttle? Pearson said, “If you do everything I just told you, you should be full throttle before you believe you can be.”

Several hours later, I won the pole position for the Darlington race in what is now the Xfinity Series.

I have carried with me the lessons I learned that day from Pearson all my life.

What I have understood better than anything at any point in my career is to listen to the great drivers, the same way Tony Gwynn listened to Ted Williams or Tom Brady would listen to Joe Montana.

David Pearson would have been great in any era of NASCAR racing, because great drivers have the sixth sense ability to discover and resolve a car and a track’s limits, much quicker than most.

I realized on that day that your body will eventually fail you in an attempt to stay relevant, but your mind seldom does. Pearson is one of the few legends I’ve been around who believed he could hop in your car and make it go faster than you. It’s not that he often said it, but it existed in his presence.

Regardless of how many years he had been retired, every time I saw Pearson, he had the appearance of being capable of still competing and an expression that suggested he was waiting only for the invitation.

I’ve listened to so many stories told by Jim Hunter, Leonard Wood, Eddie Wood and many others who associated with Pearson.

One story that has been told and retold is of the mutual respect Pearson and Petty had for one another and how they generally complimented one another as being the best in their sport. But on this day, gathered together in a small crowd, when Petty was asked who is the greatest race car driver in the garage, Petty responded by pointing to Pearson. When the gentleman posed the same question to Pearson, he responded: “I agree with Richard.”

NASCAR was made better because David Pearson was in it.

He didn’t compete in an era where great teams and great cars were abundant like they are today. He clearly had the once-in-a-generation talent.

He was the Silver Fox, and there will never be another.