In July 2008, I sat with Jim Delany in his office at the old Big Ten headquarters, a nondescript building not far from Chicago’s O’Hare Airport.

Delany had led the conference for nearly two decades. The Big Ten Network was about a year old, and it had recently gained distribution on Comcast following a difficult and drawn-out negotiation with the cable provider. The Rose Bowl agreement and other bowl pacts were strong. The Big Ten had representation in recent Final Fours and BCS national title games. The league’s lucrative media rights agreement would last another eight years. Conference realignment was quiet.

If Delany had an exit plan, the timing lined up. When I asked about retirement, Delany said he still enjoyed the job but didn’t expect to do it longer than former SEC commissioner Roy Kramer (1990-2002) or Tom Hansen, who would step down the following June after 26 years leading the league then known as the Pac-10.

“I think I’ll be here for the next five years or so,” Delany told me. “That’s my horizon.”

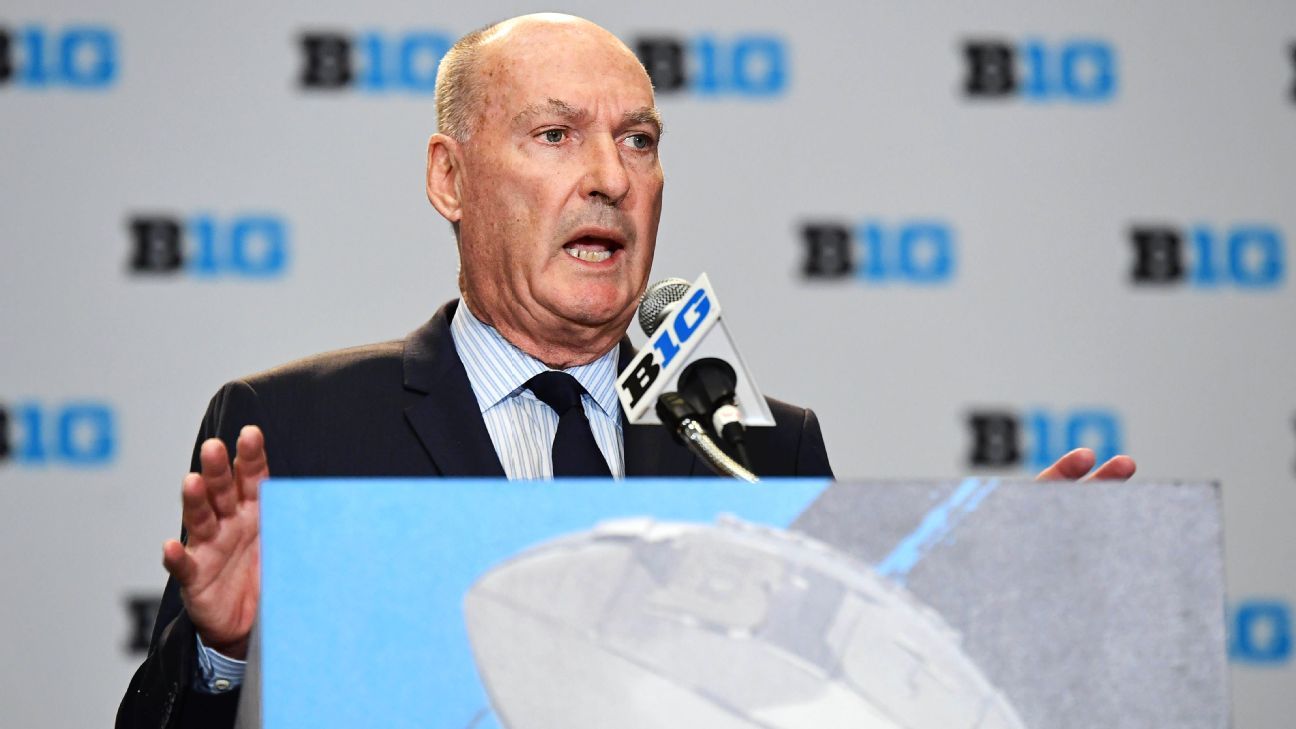

I’ve reminded Delany of his career prediction several times in recent years. I did it again Monday, when he announced his tenure as Big Ten commissioner will end in June 2020, at the completion of his contract.

“I was 60 and I was working through the Big Ten Network,” Delany said of his initial forecast. “A reasonable horizon was five years, probably. Our presidents and I talked about it, and we pushed [the contract] out to ’15, and then we pushed it out to ’18, and then we pushed it out to ’20.

“We’re just not pushing it anymore.”

If nothing else, Delany, who turned 71 on Sunday, pushed the Big Ten during a 30-year run as commissioner that likely will never be replicated. He pushed expansion. He pushed instant replay. He pushed a league-owned television network. He pushed for historic media-rights agreements that brought in record revenues for Big Ten schools. He pushed for more competitive scheduling in football and basketball. He pushed colleagues and competitors, both inside and outside the league, in both public and private debates.

He pushed a tradition-heavy league that, at times, needed to be moved forward.

Sometimes Delany pushed back, too, even to his detriment. He pushed back against a college football playoff system, even when public sentiment had swung resoundingly against the BCS. He has pushed back against pay-for-play and legal challenges to the scholastic model in college sports.

But the former point guard from Jersey is rarely pushed around.

“It’s easier to be a good player on a great team than a great player on a bad team,” Delany said. “Here, I’ve really learned to be a pass-first point guard, to get the ball to the right people and allow them to do their jobs and be supportive of them. I’ve had a fabulous team here at the conference office, and have had very talented people in our campuses.

“My knack has been to see around the corner a little bit, but also empower people around me and try to bring people together.”

Delany told me that when he became Big Ten commissioner after a decade leading the Ohio Valley Conference, he expected to serve for five years. If he had retired in 2008, 19 years into his tenure, he still would have been regarded as one of the most significant figures in college sports history. But some of his most important work occurred during his third decade as commissioner.

The league twice expanded, adding Nebraska in 2010 and then both Maryland and Rutgers in 2012 (remember, the Big Ten started the national realignment conversation, too, announcing in December 2009 that it would study the possibility of adding a 12th member). Long seen as a blockade to a playoff system in football, Delany participated in the planning to get a four-team system launched.

In 2013, Delany presented a plan where student-athletes could get more from their athletic scholarships. He negotiated a media rights agreement with ESPN and Fox, announced in 2017, which brings in $2.64 billion during its six-year cycle.

He also encountered several major scandals at Big Ten schools, including Penn State and Michigan State.

“The world changed, between expansion and media, some scandal for sure and some successes,” Delany said of his last 10 years on the job. “The opportunities that were created, the decisions that had to be made. Just the pace, the energy, and for me it was good. I like fast pace, I like energy and I like a dynamic period of time. The first 10 years was a slog — new athletic directors, new presidents, new job. The middle was kind of a settle-in period, and the last 10 have been very dynamic.”

There are two areas where Delany’s legacy doesn’t match up like it should (not counting the constant misspelling of his last name)

One is his reputation among fans, which should be better than it is. Commissioners don’t get standing ovations, but the disdain for Delany is overdone.

Big Ten fans: Delany is most significant non-coaching figure in your league’s history, period. Facilities and coaching salaries don’t just happen. Neither do athletic programs that sponsor a bunch of sports that don’t make money. Do you like seeing every football and men’s basketball game on television? Ask Pac-12 fans how that’s going. The Big Ten shares revenue equally and doesn’t have much internal squabbling. That’s Delany’s doing.

Sure, he can come across as arrogant and, at times, combative. He didn’t regularly go to breakfast with a group of reporters like the late SEC commissioner Mike Slive did. He’s not always warm and fuzzy, although I’ll never forget when he called to express his condolences after my sister died suddenly in 2013.

Not everything he did worked. His position on the BCS and protecting the Rose Bowl became annoying as the public became increasingly pro-playoff. Legends and Leaders were panned (justifiably for the names, but not the intent, which was to create divisions based on competitive balance). The Maryland and Rutgers additions remain mostly unpopular. Moving the Big Ten men’s basketball tournament to Washington and New York didn’t go over too well.

But on the whole, Delany’s achievements outweigh his shortcomings by tenfold.

The other incongruous element is the Big Ten’s lack of national championships in major sports during his tenure. The Big Ten has just three football national titles since 1989 (won by only two schools). Delany became commissioner just months after Michigan won the men’s basketball national title, but the league since has only one other hoops championship, by Michigan State in 2000, although there have been nine Big Ten runners-up with six schools represented.

Delany’s own athletic career ended with North Carolina basketball. He can’t actually win titles, but he has set up the Big Ten to win more than it has.

“That element, I’m fan and a competitor as well as a commissioner,” he said. “I love to win the games, but I try not to whine or complain. If you go back 40 years, I don’t think you’ve heard a negative word about a seed or a selection into the [NCAA] tournament, nor have you heard one about a selection into the CFP or the BCS. I don’t do that.

“I would have loved to have won more, but that’s kind of fool’s gold, whining about what you do or don’t do.”

Delany did plenty as Big Ten commissioner, and his successor will be filling massive shoes. The league’s presidents and chancellors, along with the executive search firm Korn Ferry, will conduct the search. Expect the league to look for younger candidates who can keep the job for a while (founded in 1896, the Big Ten has had only five commissioners). Northwestern athletic director Jim Phillips and Fox Sports president Mark Silverman, who was BTN president for the network’s first decade, would both be strong choices.

Not surprisingly, Delany isn’t retiring. He might consult or speak or teach (probably all three). Delany, who at 64 climbed Mount Kilimanjaro, remains in great shape. He will be “low-key” when it comes to the search for his replacement.

“Just leave it as best as you can,” Delany said of his advice to his successor. “We’re in a fast-paced world. If you don’t like managing change, then you probably shouldn’t hang in there.”

Delany hung in there for 30 years. And the Big Ten is better off for it.