A few nights ago, Peter Bayer pulled up to a Cheesecake Factory in Scottsdale, Arizona, about 20 miles north of Hohokam Stadium, where the Oakland Athletics play their spring training games, to collect an order. He was there moonlighting for DoorDash, a food delivery service, while his day job as a professional baseball player was on an indefinite hold.

This order, Bayer realized with a thrill, was for a family, which meant he’d be paid slightly more than for a typical delivery. He’d also picked up and dropped off multiple single bags of McDonald’s and Smashburger that night, driving back and forth through the Arizona desert in an effort to make ends meet after baseball was suspended in the wake of the coronavirus outbreak.

Bayer, a relief pitcher for Oakland’s high-A affiliate in Stockton, California, began driving for DoorDash on March 12, when minor league baseball officially halted its season. He made $62 for three hours of work on the first night and, after continuing to deliver food for five days, had collected $250 — pretty good money, he says, especially considering the alternative. The DoorDash app told him that he averaged $17 an hour, more than double what he earned per hour working out of the bullpen.

“Everybody who plays minor league baseball knows,” Bayer said, “that we’d make more if we worked at McDonald’s.”

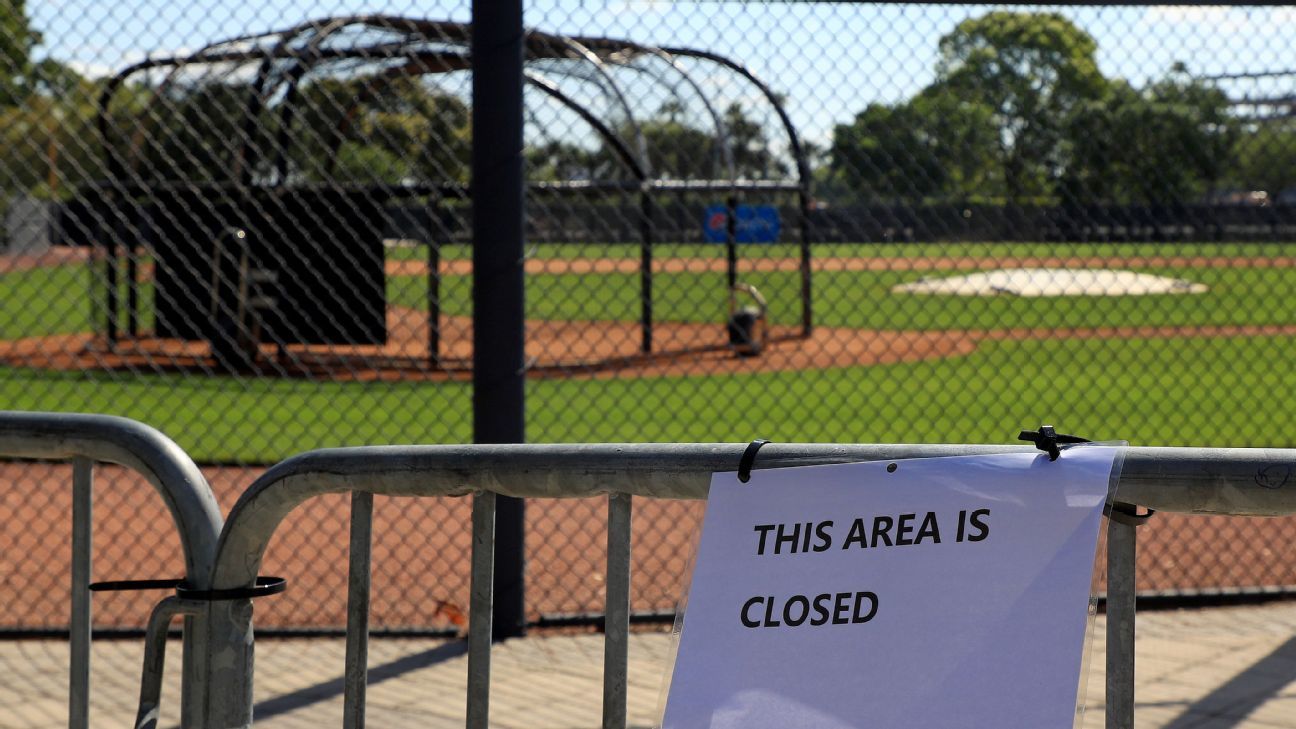

As the coronavirus outbreak has shut down baseball, minor leaguers have been thrust into a particularly precarious situation. Most of them earn low pay during the season — players in Class A made, on average, $5,800 last year — and don’t get paid at all during spring training. Now the pandemic has sent them all home from sites in Arizona and Florida (major league players are permitted to stay), and it’s anyone’s guess when they’ll return or get paid again. Minor leaguers’ pay isn’t protected by federal minimum-wage law. Players aren’t eligible for unemployment because they are technically under contract to their affiliated MLB clubs. Unlike their major league brethren, minor leaguers aren’t unionized. Some minor league players have not been paid since their previous seasons ended last August.

MLB announced on Thursday that minor league players shut out of spring training camps will receive, in a lump sum, per diem allowances from teams through April 8, the previously scheduled end of spring training, and the league is working on a plan to compensate those players during the postponed portion of the regular season. When contacted by ESPN, an MLB spokesperson said, “We have increased allowances provided to minor league players in order to assist them and their families in navigating this difficult time.”

That will help, but Bayer and thousands of other players remain in limbo until the rest is figured out.

After a few more trips with DoorDash, Bayer, 26, decided on Tuesday, less than a week after the shutdown, to drive back to his hometown of Parker, Colorado, a Denver suburb. Since it’s clear the season won’t start anytime soon, he moved back in with his parents. Bayer said the A’s gave their minor league players $200 to cover travel, which Bayer spent on gas and one night in a Drury Inn in Albuquerque, New Mexico, the midway point of his 12-hour Arizona-to-Colorado trek.

Bayer still hopes to work at an indoor baseball facility while he’s home, but first he had to find another source of income because he had some debt to pay down. There were already so many DoorDash drivers, people who are out of work delivering to people stuck at home, so he looked elsewhere. On the drive home, Bayer got good news. He had been approved for a job with Shipt, a service for which he can deliver groceries to homes.

While Bayer is appreciative of the per diem — he told ESPN that players will get $400 a week through April 8 — it won’t mean he can quit his (new) day job. “I’ve spoken to a few other players about it,” Bayer said Thursday. “We’re glad we’re getting something. But we still have no idea what’s going to happen after April 8.”

“I don’t know where or who I’m going to train with,” said Mitch Horacek, a pitcher in the Minnesota Twins organization, on Sunday. “I don’t know if I’m going to get paid, which is a huge deal, because I haven’t gotten a check since August.

“They told us, ‘Stay ready.'”

Horacek described the first few days after the shutdown as a “s— show.” He said Twins brass met with players at the team’s facility in Fort Myers, Florida, on March 12, after the season was put on hold. The message: Hang tight, tomorrow is a day off, we’ll figure this out. On March 13, they called another meeting. The mood this time was somber, as general manager Thad Levine and assistant GM Rob Antony took questions from concerned players.

“At the end of the day, they told us, ‘Get out of here,'” Horacek said.

Players from the Twins and many other organizations did leave, but the initial mixed messages about how players should proceed threw their lives into chaos, a minor leaguer in an American League organization — who preferred to remain anonymous because he worries that complaining publicly will put his career at risk — told ESPN.

“Minor league players don’t matter in this situation,” said the player, who has spoken with numerous fellow players from other organizations over the past week, and describes their collective mood in the wake of the season being suspended as “panicked.”

During a team meeting after it was announced that baseball was shutting down, another player asked representatives from his team, the Braves, if he could continue to work out at the team’s spring training facility. They told him it would be locked.

Since baseball suspended operations, the league has negotiated with the Major League Baseball Players Association on a variety of topics, including how salaries would work in shortened major and minor league seasons. No decision has been reached. Teams also pledged $30 million to help cover the lost wages of ballpark employees, and announced a joint donation with the MLBPA of $1 million toward feeding children and senior citizens affected by the coronavirus crisis.

Many players have reached out to More Than Baseball — a nonprofit that provides money, equipment and advice for minor leaguers — for help. Co-founder Jeremy Wolf, a former outfielder in the New York Mets organization, said the nonprofit heard from 250 players over the weekend.

“We’ve been asked questions about every team,” Wolf said. “How long are they going to be gone for? What do [Latin American players] do? If they stay, are they allowed to go to the complex and work out? Are they getting meals? Are they getting stipends? What happens when the season starts and they’re not getting money? Can they file for unemployment?”

Only some of those questions have been answered since.

Teams do pay for players’ transportation home. Those from Latin American countries have to leave, too, unless it’s not safe or feasible for them to do so. However, the players interviewed each told ESPN that it’s too late, in many cases, to determine feasibility; some players from Latin American countries — such as Venezuela — already have been sent home. Another player who was sent back to Panama told a fellow player that he can’t afford diapers for his child.

More Than Baseball has set up a fund through its website that allows major league players — and anyone else — to donate to a fund for minor leaguers. Any donation from a major leaguer will be matched by the MLBPA.

More Than Baseball also has partnered with the Adopt a Minor Leaguer initiative, which matches players with fans who want to send them care packages. It was formed, Wolf said, after a Twins fan whose father had been diagnosed with lung cancer decided to help out a player in need. Wolf said the nonprofit is creating an online portal, similar to LinkedIn, where minor leaguers can connect and advise each other about jobs, nutrition, housing and more.

According to Wolf, More Than Baseball was formed on the same day in March 2018 that Congress approved a $1.3 billion spending bill. On Page 1,967 of the 2,232-page document was the “Save America’s Pastime Act,” which exempts minor league players from federal minimum-wage law and allows major league teams to pay them like seasonal employees.

MLB announced last month that it will raise minor league salaries for the 2021 season (the San Francisco Giants and Chicago Cubs are raising wages for this season; the Toronto Blue Jays did so in 2019). Players earn a minimum of $14,000 in Triple-A, but many, including most in the lower levels, will remain below the poverty line ($12,490). This all comes as the Professional Baseball Agreement is set to expire after the 2020 season, and MLB has talked about cutting 42 minor league teams.

On Sunday, a minor leaguer in the New York Yankees organization tested positive for the virus, the first known case in baseball. (A second minor leaguer in the Yankees organization has since tested positive.) The Yankees told all of their minor league players to remain isolated in the Tampa, Florida, area for two weeks. The team is covering their hotel room costs and paying for food delivery to their rooms.

Horacek, the hurler in the Twins’ system, isn’t in isolation — but without access to a workout facility has been forced to workout wherever he can. A trainer from his home gym in Colorado texts him a daily workout regimen.

“[The Twins] sent an email to us regarding the coronavirus that said, ‘We want you to know that we are going to get through this and we will do that together,'” said Horacek, who signed with Minnesota during the offseason after seven seasons with the Rockies and Orioles organizations. “I replied to that email and basically said, ‘Listen, I don’t trust MLB to take care of us. I’m your employee. You don’t really know me, but I hope you take care of us. Think about us.'”

[Horacek spoke by phone Thursday with Twins president of baseball operations Derek Falvey, who told him about MLB’s per diem plan. Said Horacek: “I was appreciative that he took the time to talk to me. He’s been very busy trying to navigate this unprecedented time in baseball, and given the fact that MiLB players don’t have a seat at the MLBPA negotiation table, it was nice to have my voice heard by somebody at the top.”]

Last Friday, Horacek hitched a ride with his girlfriend from Fort Myers to her mother’s house in Jupiter, Florida, where he has been staying while awaiting word about what’s next.

On Saturday, he tweeted to ask if any baseball players in the area wanted to long-toss with him. He got a response from Jack Corkery, a pitcher at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania, who is staying at his parents’ house nearby since his school was closed and his team’s season canceled 12 games into his senior year.

The pair went to a park in Jupiter less than a mile from Roger Dean Chevrolet Stadium, the spring training home of both the St. Louis Cardinals and Miami Marlins. In the park, Horacek and Corkery shared space with two high school players and ran into Jeff Brigham, who is on the Marlins’ major league roster. It was an impromptu baseball commune.

With the nearby stadium closed, Horacek stood on a soccer field — used by the middle school across the street — and played catch.

Like many people across the country, he was making the best of things while his life — and livelihood — are up in the air.

Chris Rowley tore his rotator cuff and partially tore his labrum on March 8, four days before minor league baseball shut down indefinitely, while throwing in the bullpen before he was set to toss live batting practice.

Rowley, a right-hander in the Twins organization who appeared in eight major league games with the Blue Jays, was scheduled to undergo shoulder surgery this week or next — after which he faces 12 months of rehab.

But Rowley found out that his surgeon, like more than 10,000 other Americans so far, had contracted COVID-19. So his procedure is on hold. For now, Rowley has decided to remain near the Twins’ spring training site, where he says the organization is doing its best to help him reschedule the procedure.

“Elective surgeries are taking a back seat during this pandemic, and rightfully so,” Rowley said.

Rowley has more leverage than most minor leaguers. Thanks to his big league experience, he was able to negotiate a deal that will pay him about $6,000 every two weeks instead of the $850 he got in Triple-A in 2017. But he realizes that most of his colleagues are not so secure.

“If April 15 rolls around and we still aren’t receiving paychecks, there are going to be hundreds, if not thousands, of pro baseball players in dire straits.”