Pakistan 249 for 6 (Imran 72, Miandad 58, Pringle 3-22) beat England 227 (Fairbrother 62, Akram 3-49, Mushtaq 3-41) by 22 runs

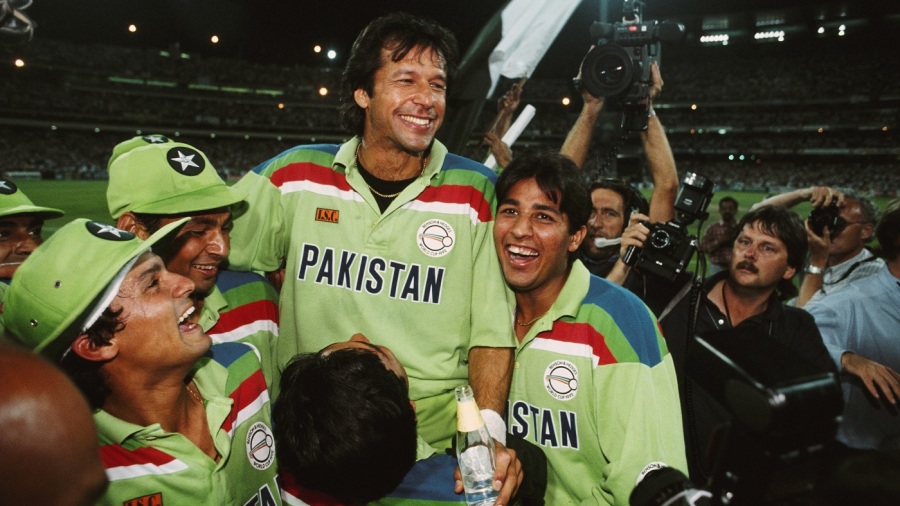

In the end, it had to be Imran. Pakistan’s captain, leader, talisman and icon is into his 40th year and will surely never be seen again on a cricket field after this, the triumph to end all triumphs. But when, with the game out of reach for England and only pride left to fight for, Richard Illingworth launched a tired wipe to Rameez Raja on the edge of the ring, it was Imran Khan, the bowler, whose upraised arms confirmed the end of a career-long quest, and the seizure of Pakistan’s maiden World Cup triumph.

The scorecard will say that Pakistan outlasted England to win by 22 runs – and Imran’s role was fittingly front-and-centre, in particular a captain’s innings of 72 that set the agenda for everything that followed. And yet, the numbers tell only a fraction of the story of a fraught, tense encounter in which a sprinkling of magic proved the difference between the teams.

The match panned out much as the two teams’ runs to the final had done – England, the early pace-setters, pushing Pakistan to the absolute brink in the opening exchanges, only for a few moments of good fortune to turn the tide and drain the energies of the men in light blue. And then, slowly at first, but then in a crescendo with bat and later with ball, Pakistan shed their inhibitions and turned to their inner tigers to finish with a roar that no opponent could have withstood.

The critical moment came as the players paused for drinks after 34 overs of England’s run-chase. Faced with a stiff target of 250, England had been rocking at 69 for 4 but found, in Neil Fairbrother‘s eye for a deflected single and Allan Lamb‘s old-school pugnacity, a fifth-wicket pairing with the requisite fight to take the game deep. Their stand had exactly doubled England’s total to 138 and reeled the requirement back to a manageable seven an over, when Imran decided it was time to turn back to his strike bowler, Wasim Akram, with licence to let rip.

It was a moment by which legends are born. After another new-ball burst in which Wasim’s consummate skill had been undermined by the degree of movement on offer, his return with an older, tamer ball wrecked the contest. With reverse-swing from the outset, England were on their guard, but even knowing what was liable to come his way, Lamb had no response to a delivery from the Gods, an inswinging, out-seaming gut-twister that snaked one way then the other, opening the batsman up like a can of worms before kissing past a groping edge to flick the outer half of his off stump.

ALSO READ: Akram gets into the swing of things

And if that was good in isolation, then the follow-up to Chris Lewis conferred the double-whammy instant iconic status – a flip of the shiny side of the ball to unleash a howling inswinger, one that started so wide of off stump, Lewis might have believed it would be called as such, before hurtling back through his defences as if caught in a gravitational pull, to smash the top of the stumps, and confirm that England’s hopes were gone.

Fairbrother withstood as best he could, top-scoring for England with a gutsy 62, but Pakistan had too many snake-charming overs left in their repertoire for their opponents to get back on track. If there was an error in England’s approach, it was their failure to take the attack sooner to the left-arm spin of Aamer Sohail, who burgled his way through 10 overs for 49 in the crucial mid-innings rebuild, and allowed Pakistan to paper over the fact that, with all due respect to Imran’s glorious past, they came into the game with just three frontline bowlers.

But what a trio they proved to be. Until Akram’s intercession, it seemed that Mushtaq Ahmed‘s outrageous googly to Graeme Hick might prove to be the crowning moment of the night, but his 3 for 41 was no less critical for being upstaged. In fact, in luring the ever-dangerous Graham Gooch to his doom on the slog-sweep for 29, he arguably did as much as anyone to point Pakistan towards glory.

The boy-turned-man who took that catch, sprinting, stretching, sprawling at deep midwicket for an inspired take – was the zippy seamer Aaqib Javed, whose precociously commanding performance at the top and tail of the innings returned figures of 2 for 27 to ensure that the injured Waqar Younis was barely given a passing mention. Throw in another display of unfettered strokeplay from Inzamam-ul-Haq in the latter stages of Pakistan’s innings, and it’s clear this triumph – Imran’s overlord status notwithstanding – was a testament to Pakistan’s eternal faith in youth.

But how they were made to battle by a team that came into the final as favourites after a supremely disciplined campaign, but who crucially lacked the same youthful spark to augment the ageing giants in their line-up. With the ball, Derek Pringle produced one of the great losing performances in World Cup history, and Gooch and Lamb both had their moments with the bat. But Ian Botham’s last hurrah was less of a joy. His old-pro outswingers had hoovered up 15 wickets in England’s run to the final, but just one belated scalp on the night. And with the bat, he suffered the ignominy of a sixth-ball duck, adjudged caught behind off an Akram lifter, even as umpire Aldridge was beginning his walk to square leg.

Mind you, Pakistan’s own innings hadn’t started much better. On a lively deck with juicy early movement for the seamers, their gameplan had been clear from the outset. Bed in at all cost, at the expense even of forward momentum, and trust their middle-order artillery to reprise the late onslaught that unseated New Zealand in Saturday’s thrilling semi-final.

It was a tactic fraught with risk, especially once the canny old pro Pringle had proven his fitness after missing the South Africa match with a rib injury. Manipulating the new ball like a yo-yo on its string, Pringle served up a supreme spell of wickedly intelligent medium pace, bowling eight overs off the reel for 13 runs, with only his own size-12s breaking the spell, as he overstepped for a total of five no-balls, coupled with three wides.

Pringle accounted for both openers in that first spell, Aamer Sohail for 4, who flashed with flat feet at one that nipped off the deck outside off, before Rameez Raja was pinned lbw for 8 by the inducker, a brace of deliveries that showcased his mastery of seam position, honed in so many Championship-winning seasons at Chelmsford.

But at 24 for 2 in the ninth over, and with Pakistan’s veteran pairing of Imran and Miandad already united at the crease, both teams knew that the game could be won and lost with the next breakthrough.

Initially Miandad seemed to know it more acutely than his captain. Whereas Imran was content to plant an imperious front foot down the wicket, blocking the straight ones and leaving those outside off, his partner got off to an unusually skittish start by the standards of his formidable tournament. He might have been caught in the gully on 1 as Lewis bent his back in an excellent new-ball spell, before scuffing a drive inches short of midwicket two balls later.

And then, in the space of two deliveries, came a pair of let-offs will surely haunt Pringle to the end of his days. With teasing shape back into the right-hander’s front pad, Miandad was rapped plumb in front of the stumps, then plumber still – from an even fuller length, so taking out any doubt about the height. On both occasions umpire Bucknor shook his head, and Pringle could only flap his hands in disgust, ruing a moment lost, but confident it could yet come again.

For even with those let-offs, Pakistan were seemingly going nowhere on 34 for 2 at the 17-over drinks break. But as Imran might as well have muttered during a mid-over conflab, “Ghabrana nahin hai (don’t panic)”. Sure enough, the introduction of Ian Botham broke the shackles a touch, as Miandad skipped to the pitch of a drive through mid-on for four in an opening over that yielded nine.

But it was Imran himself who had the next key let-off when, on 9 from 41 balls, Phil DeFreitas banged in a short ball that rushed onto a pre-meditated pull. Gooch at square leg, all 38 years of him, sprinted full pelt as the ball plummeted over his shoulder, but despite a valiant dive, he was unable to wrap his fingers round the chance.

Whether that was the game there and then, who knows. But slowly but surely, the MCG’s vast outfield began to look chock-full of scoring opportunities, as England’s tiring team – already feeling the strain after a long winter campaign – began to be pulled apart at the seams. From 70 for 2 at the halfway mark of the innings, the game was still in their grasp. At 96 for 2 after 30, they were getting anxious for a wicket. And at 125 for 2 after 35, with Dermot Reeve flogged from the attack with a 12-run over that brought up the hundred partnership, they were getting desperate.

Miandad, in his fifth World Cup, duly became the first Pakistani to score 1000 runs at the tournament, and by the time he was finally extracted in the 40th over for 58 – unfurling the reverse-sweep against Illingworth where conventional mowing through the line had been serving him just fine – the arrival of the helmetless Inzamam-ul-Haq, Pakistan’s break-out star of the semi-final, wasn’t exactly a blessing. At 163 for 3 with ten overs in which to make merry, the stage was perfectly set for Pakistan’s much-vaunted finishers.

Imran knew it too. On 72, having done his bit and more, he aimed an ambitious wipe at his fellow legendary allrounder Botham, and picked out Illingworth on the edge of long-on boundary. He departed to a rich ovation, safe in the knowledge that he had risen to the occasion in what will surely now be his final, final farewell. And handed the reins to his other young gun, Akram.

Between them, Inzamam and Akram drained England’s troops of their resolve, adding 75 in 53 balls between them, with Inzamam’s initial flurry of four fours in his first ten balls giving way to a supporting role as Wasim took up the cudgels in the final five overs. He cracked four fours in his 18-ball 33, including a brace of venomous swipes to wreck Lewis’s figures in his final over, and though Pringle returned to outfox Inzamam for a richly deserved third wicket, a target of 250 – four more than England had failed to chase in Calcutta five years earlier – was daunting.

And by the time Pakistan had sprinkled their magic on the contest, it was overwhelming.