With the first 10 races of the Formula 1 season either postponed or cancelled, it’s been a difficult time for racing fans to get their fix. Thankfully, Formula One has been filling its YouTube channel with retro races to bridge the gap, and watching them has highlighted some interesting contrasts between modern F1 now and the sport in the 1990s.

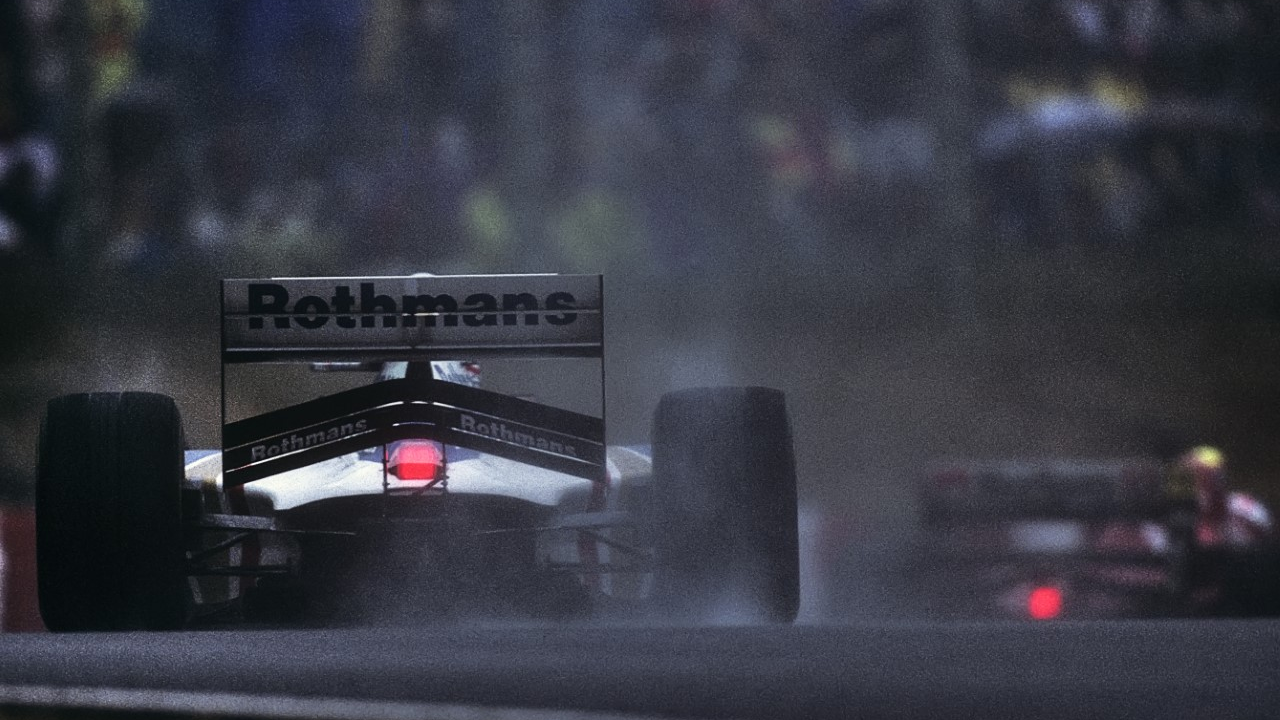

In a series of features, we’ll review the races F1 uploads on YouTube, making notes on the things that stood out most (but don’t worry, we won’t give away the result). And what better place to start than the rain-hit 1994 Japanese Grand Prix — a crucial round in that year’s championship and one that has more than its fair share of talking points.

It was a crash fest

We’re used to seeing rain at Suzuka, but there’s no way a modern F1 race would have got underway in those conditions, especially with a standing start. And rightly so.

After just 15 laps, nine cars had crashed out, eventually leading to the race being red flagged for a short period of time. The tipping point for the stewards came when Martin Brundle’s McLaren aquaplaned off the circuit at the Dunlop corner and hit a marshal attending to Gianni Mobidelli’s smashed up Footwork. The marshal’s injuries were limited to a broken a leg, but it could have been much, much worse.

Brundle himself was also lucky to escape serious injury after just missing a caterpillar-tracked recovery vehicle, in an incident not dissimilar to the one that cost Jules Bianchi his life at the same circuit 20 years later.

“I nearly killed myself against the back of a caterpillar truck, that shouldn’t have been out there anyway,” Brundle told the BBC during the red flag period that followed. “I’d already raised my concerns about that before the race.”

It was also remarkable to see drivers walking back to their garages after their crashes rather than being picked up by the medical car. An injured Ukyo Katayama, who crashed on the pit straight after just three laps, was seen limping through the pit lane with the aid of two marshals, who almost ended up dragging him the final few yards back into the garage.

It was a complete mess and a reminder of why modern-day race officials often deliberate for so long over starting races in the wet.

Aggregate racing was confusing to watch

Under the regulations at the time, a red flag split the race into two halves and the times from both were added together to give the results at the end. That meant that when the race got back underway behind a Safety Car on lap 16, the gaps you could see between the cars on track were not representative of the actual gaps in the official timing.

With limited on-screen graphics, it was the job of the commentators to explain what was happening, which Murray Walker and Jonathan Palmer did well, but it still led to some confusing moments. Combined with a loss of signal during a crucial pit stop for Michael Schumacher, anybody joining the race midway through would have struggled to have any idea what was going on.

It made for an exciting finish, but there is no doubt the current rules, which simply reset the gaps between drivers after the red flag, is a better solution.

The Safety Car was a Honda Prelude!

Although Safety Cars had made appearances at F1 races at various times in history, it was only in 1993 that they were officially introduced. As a result, the presence of the Safety Car in 1994 was still something of a novelty and its first appearance in the race saw Schumacher, who was leading the pack, fail to catch up with it for several laps. That was more a result of the conditions than the speed of the Safety Car, which, remarkably, was a Honda Prelude.

The fact it was a Honda was perhaps no surprise as each track supplied the Safety Car in those days and Suzuka was (and still is) owned by Honda. But the choice of a Prelude — a two door version of the Accord family car — was … interesting. To give some perspective, the top-spec Prelude in 1994 had a power output of 197 bhp and a top speed of 144mph. Not too shoddy for the period, but hardly the spec of car needed to keep F1 tyres at their minimum operating temperature.

What’s more, a short clip during the red flag period showed the circuit also had a red Honda NSX available as a course car. Which begs the question, why didn’t they use that? The NSX was a proper sports car and had been developed with help from Ayrton Senna, making it a far more logical (and exciting) choice of Safety Car.

In the end, it didn’t make a huge amount of difference as the conditions were so bad when the Prelude Safety Car was on track, that it could have been a Honda Civic and the result would have been the same.

Mansell was still fantastic to watch at 41 years of age

Nigel Mansell made four appearances for Williams in 1994 at the French, European, Japanese and Australian Grands Prix. The 1992 champion was drafted back into the team after the death of Ayrton Senna to share the second Williams drive with David Coulthard after Damon Hill was promoted to the team’s No.1 driver role.

Mansell was racing in IndyCar at the time, but F1 owner Bernie Ecclestone helped broker a deal with Newman/Haas Racing to allow him to race for Williams in F1 when there were no clash with his racing duties Stateside. The deal was especially sweet for Mansell, who was reportedly earning £900,000 per race, dwarfing the £300,000 teammate Hill was receiving as a retainer for the entire season!

As a result, Mansell lined up on the grid in a Williams for the Japanese GP and, despite being slightly off the pace of Hill in qualifying and the race, was hugely impressive to watch. Large parts of the lead battle between Hill and Schumacher were actually pretty dull, but Mansell’s fight with Jean Alesi’s Ferrari was thrilling to watch from start to finish. Mansell was stuck behind the Ferrari and, on aggregate after the red flag, had to pass and pull away by over five seconds to finish on the podium.

At 41 years old, Mansell looked as determined as ever as he took a risky wide line through Spoon corner in an attempt to pull a move into the high-speed 130R after the back straight. Combined with the glorious soundtrack from the onboard footage of Alesi’s V12 Ferrari, the racing is some of the best you’ll see in any decade and both drivers display immense bravery fighting over the position. We won’t ruin the outcome for you, but afterward the two giants of ’90s F1 shook hands and congratulated each other in parc ferme.

The cars were more entertaining to watch

It’s easy to don rose-tinted spectacles and proclaim the 1990s F1’s golden era, but even without the hyperbole there’s no denying it was a fantastic spectacle. The basic shapes of the cars are far more appealing than the modern beasts and the soundtrack of naturally-aspirated V8s, V10s and V12s can’t be beat.

The driver’s skill was also so much more obvious. It was common for the cars to be pitch into four-wheel drifts on corner exit and the amount of serious accidents that year, while shocking, stood as a reminder of how much was at risk in doing so. That’s not to say modern racers aren’t as talented or brave, but it’s simply that their skills are not as visible from the outside in modern cars.

What’s more, the low cockpit surrounds, which were rightly banned for safety reasons in the following years, allowed a much better view of the driver at work. Even form the fuzzy TV pictures, it is possible to see Schumacher’s helmet leaning out of the cockpit as he prepares his neck for the G-forces felt in each corner of Suzuka’s famous Esses.