LEG· A· CY

Noun

Something transmitted by or received from an ancestor or predecessor or from the past. — Merriam-Webster

Professional athletes in the television age have absconded with the word legacy and returned it mangled beyond recognition. Seemingly every basket, home run or touchdown is accompanied by a player absorbed by his own moment, breathlessly declaring, I’m just trying to cement my legacy, when he’s actually just adding to his accomplishments. There’s … a difference.

Legacy is what is left after there are no more clutch jumpers to make and no more opponents to stare down. It isn’t what you’ve done but what it will mean. Legacies cannot be immediately assessed, for they have nothing to do with the present. They’re not about you. At the end of 1998, Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa thought their legacies were secure, and they were — but not nearly in the way each envisioned. You must wait and see what time does to your time. Legacy is not yours. It’s how the rest of us navigate what you’ve left in your wake.

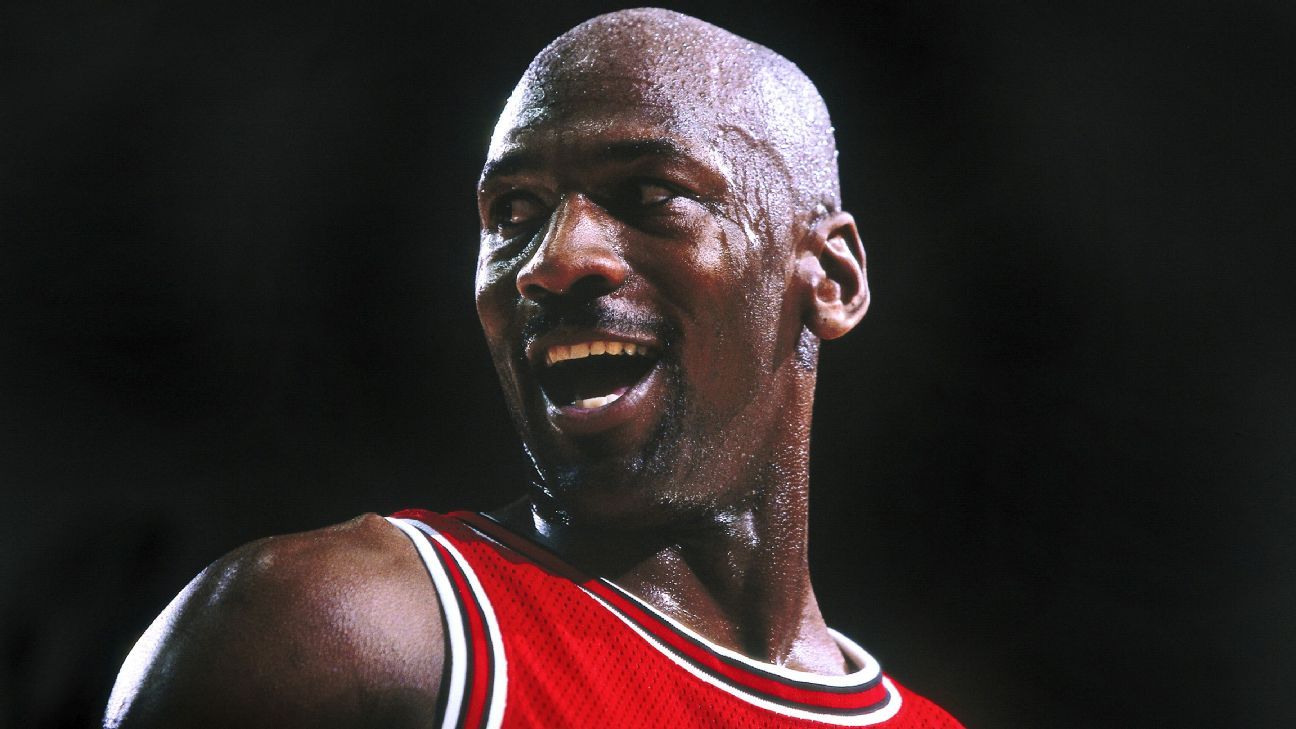

Few boats have left a larger wake than Michael Jordan. At a remove, weeks after the ESPN premiere, following the ABC encore and now about to head to Netflix (July 19), his documentary, “The Last Dance,” still reverberates. Twenty-two years removed from when he took his last shot in a Chicago Bulls uniform in 1998, the reappearance of Jordan in “The Last Dance” reminds me of an old joke from my Irish friends growing up in Boston, when they would ask if I knew what “Irish Alzheimer’s” was. When I said no, they would respond, “It’s when you forget everything — but the grudge.” They would laugh because it was funny and they would laugh that intra-clannish laugh reserved for people in the tribe because it reminded them of some fond relative for whom they knew it was fearsomely true. Jordan is of a different tribe, but the grudges still hold, alive, fierce. He has forgotten none, forgiven even fewer.

The film affirmed that his dominance was as we remember, while also confirming darker suspicions. To teammates, Jordan resembled Darth Vader in “The Empire Strikes Back,” killing anyone who disappointed him. To adversaries, he was Michael Corleone in “The Godfather,” unsatisfied in defeating all rivals, unsatisfied in his net worth exceeding that of Bulls and White Sox owner Jerry Reinsdorf — the same Reinsdorf who once, in a streak of envy toward Jordan, attempted to reduce him to a mere laborer, saying, “Unlike him, nobody signs my checks.” Unsatisfied even in total victory. Michael Jordan has more bloodlust in him, but his moment has passed, there’s no one left to kill, and time — the rival that motivated him to do the film in the first place — can never be defeated.

Jordan lived for the kill, but for all the gossipy sensation of Jordan and Horace Grant calling each other “snitches,” for all the cringing as we watched him humiliate role players on his own team, I thought about Jordan through the true meaning of legacy, about what this ancestor left behind.

WE ALL (THINK WE) ARE JORDAN

About 15 years ago, I argued about universal health insurance with someone stupid, which makes me stupid, and I lost count of the number of times he used the term “socialized medicine,” even though life, auto, house, renters and all other types of common forms of insurance in the United States operate along the same socialized premise: The community pays into the whole for a service you generally do not need — until you do. Your contribution helps take care of other people until the time comes for it to help take care of you. He was unmoved, even when I told him America already practices various forms of universal health.

“If you don’t have insurance, broke your arm and went to the ER, they would still treat you,” I said. “They wouldn’t leave you in the street untreated. Who pays for that? We do. The rest of us.”

“Well, you shouldn’t,” he said. “Leave me on the sidewalk. Why should I be forced to pay for something everyone else uses when I’m perfectly healthy?”

He might have been stupid, and in that moment might have left no doubt, but he also represented a common strain of American individualism, of doing it yourself. No help. No handout. No teamwork. No one to pass the ball to, and no one getting the assist. Americans often believe the person next door is receiving something unearned, something free off of their backs. I work harder than you. Right now someone is complaining about work, about how they are the only ones doing their part, surrounded by the weak links who don’t measure up but want the same reward. They watch the Jordan work ethic, see the results, and see themselves. They relate to Jordan’s single-mindedness when he says early in the documentary that he never asked his teammates to do anything he wasn’t willing to do, and they identify with him justifying his abuse of teammates because his exacting professionalism matches their idealized view of their own — without considering they might instead be Scott Burrell.

Validated by championship results, Jordan sanctified the template of the leader-as-monster, out of necessity. It has been mythologized in sports, by abusive coaches everywhere and recently by the late Kobe Bryant, that punching down on those who are less talented is the champion’s way and those who disagree are losers who simply lack what it takes, who, in Jordan’s words in the documentary, “haven’t won anything.”

“People wanted to get some insight into Michael Jordan: the über-competitiveness, the drive, and we brought the mask down,” the film’s executive producer, Mike Tollin, told me. “Nick Saban is clipping Michael’s lines at the end of Episode 7 to show his football team about what greatness means and what it takes. Business leaders are doing the same thing. Captains and kings of industry are now referring to it.”

Yet all the fantasy glamorization of Jordan’s single-mindedness lands differently in 2020, when universal health care — the concept of a nation using taxes to take care of one another — is now widely accepted. The obsessives like Jordan are now more isolated and even, at times, discredited. The culture still loves the result but is less tolerant of the genius-tyrant. Work-life balance is a thing. Even ballplayers now take time off during the season for the birth of their babies — and the world doesn’t collapse. Caring about one’s family doesn’t make you an unserious professional.

Yet Jordan satisfies two concurrent fantasies. The first is that the tyrant who abuses subordinates does so not because he is a tyrant who cannot control his emotions but because he is correct; he is being dragged down by the lesser around him, and that justifies his rages. The second is that we are all Jordan, undermined by people who don’t put in the work we do. His disdain for his teammates reflects our own. Few people ever toss one back after work and tell people they’re the Bill Cartwright of the office. There was a time when Bobby Knight was glamorized for the same ruthless qualities people glamorize in Jordan. Maybe there’s another way.

YOU PROTECT YOUR OWN TIME

I’m a child of the late 1970s and 1980s, of Bruins vs. Canadiens, Red Sox vs. Yankees, Evert vs. Navratilova, Cowboys vs. Steelers, and, of course, Bird vs. Magic. The release of the 1996 movie “Space Jam” was not a momentous occasion. It was just a kids movie. “The Last Dance” was a reminder that I feel no proprietorship for Michael Jordan. His era was not mine, and therefore for me it’s not protected behind bulletproof glass. He is the younger generation’s Bill Russell, their Jim Brown, their Sandy Koufax. He is the guy who made the old-timers watch like the brothers in the barbershop who used to say if you didn’t see Jim Brown play, you never really saw football, or all the New Yorkers who swore if you missed Joe DiMaggio, you missed perfection and would never see it again.

Jordan doesn’t reflect only himself, but rather the sanctity of a generation for whom the perception of things like the Knicks vs. Bulls mattered most because the grown-up stuff hadn’t yet arrived. He is the mirror of their most beautiful selves. At one point I texted former pitcher CC Sabathia:

ME: You watching Jordan?

CC: Man, I already seen it. Best doc of all time but I’m biased. Hahaha.

ME: Why biased? Jordan brand?

CC: ‘Cause I’m a Jordan fanatic.

Throughout the month the film aired, when even the slightest comment about Jordan was received as vicious criticism, the question reverberated: Why is it so important that Michael Jordan remain unimpeachable?

I don’t have 10, but the eight best basketball teams I’ve personally witnessed were the 1980s Lakers and Celtics, the 1980-83 76ers, the Curry Warriors, the Kobe-Shaq Lakers, Duncan’s Spurs, the Bad Boy Pistons and the Jordan Bulls. I cannot say one is better than the other seven, and need not, for it is generally unimportant. Each dominated its time and each has been eroded a bit over time because that’s what time does — all except for Jordan. Jordan’s is the monument most fiercely guarded, that brooks no debate, the one we are told could time-travel into any era and emerge victoriously, that, like Jordan himself, demands complete submission. Perhaps the reason is that Jordan went 6-0 in NBA Finals and won the Finals MVP in each. Perhaps it is because Jordan’s teams never trailed after three games of any Finals series. Perhaps, but I do not think so.

The Showtime Lakers’ legacy carries the burden of Magic’s air ball against the Houston Rockets in the first round of the 1981 playoffs, letting the Celtics off the hook in the 1984 NBA Finals and Ralph Sampson two years later in the Western Conference finals. Larry Bird went 1-2 against Magic in the Finals. Detroit had a short championship run. Bill Russell’s untouchable eight straight titles, 11 in 13 years, occurred when the league was a third of its current size. LeBron is 3-6 in NBA Finals. The 2015-16 Warriors won 73 games but not the title. Given all of that, surely the legacy of Michael and his Bulls must carry a burden. They dominated a soft patch in the NBA when Showtime and the Celtics faded and San Antonio and Shaq-Kobe hadn’t yet arrived. The Bulls never faced an all-time great Finals opponent, and no player Jordan faced in the Finals, other than an aging Magic on a hodgepodge ’91 team, was a top-10 all-time great. (Sorry, Mailman.) Surely, Jordan’s legacy must carry a 2-5 postseason record against Bird, Magic and Isiah Thomas, having never won even a single playoff game against Larry Bird the player, yes?

No.

Like Jordan himself, Jordan protectors remain undeterred, unwilling to concede even a point. The real reason, I suspect, is that Michael Jordan stands as the godfather of the modern, global game, when all of the things came together at once. He was the most exciting aerial player with enormous style influences beyond basketball — from head (the Jordan shaved head was cool, the Slick Watts clean head an oddity) to waist to, most defining, the shoes. Jordan connected to his generation’s sense of identity far beyond the game. And while winning so much, people forgot he ever lost. He is the only A-list, Hall of Fame superstar in NBA history who was never dethroned on the court as defending champion. When the Bulls failed to defend their 1993 title, Jordan was lunging at curveballs in the minor leagues. When he was knocked out of the 1995 playoffs after his return, the Houston Rockets were defending champions. When the 1999 Bulls didn’t even make the playoffs, Jerrys Krause and Reinsdorf had blown up the dynasty. Jordan was retired. Whenever Jordan returned to the court after winning a championship, he won another one.

More from Howard Bryant

Within this framework, “The Last Dance” risked offering only hagiography, an entertaining reminder of who was in charge, a reinforcement of the unimpeachable man. Jordan is not reflective on camera. He does not offer the panoramic insights time is supposed to afford. He is singular, as he was during his time, the undisputed point of the pyramid. If “The Last Dance” is an accurate lens of how Michael Jordan wanted to be seen, it was a world without women in the foreground. The only spouse/girlfriend in the entire documentary is, yes, Carmen Electra, who was dating Dennis Rodman at the time. Michael Jordan travels from the locker room to the cigar bar. He is the alpha male.

His first wife, Juanita, is never directly mentioned. His current wife, Yvette Prieto, is not mentioned at all. At no point over 10 episodes does Michael Jordan refer to his family, wife and kids as a refuge from the pressures of the world, an anchor, a source of joy where he refuels what has been expended from the fight. Outside of his mother and father, and growing up, he doesn’t refer to family. He is now as he was then: the athlete incarnate, showing no weakness, even equating regret or compassion to weakness. Scott Burrell, Jordan reminds us, is “just a nice guy.” By this stage in the journey, we are expected to age and reflect and reconsider. Michael Jordan appears only to be aging.

CONTROL

In 2018, the Pulitzer Prize-winning book critic Michiko Kakutani eviscerated the Trump administration’s habitual lying to the public in her book “The Death of Truth: Notes on Falsehood in the Age of Trump.” Twenty-three years earlier, in 1995, just as Jordan was returning to basketball, Major League Baseball attempted to circumvent the free press by starting its own news website, MLB.com. So began an era of sports leagues competing with traditional media — NBA TV, NFL Network, NHL Network and MLB Network. In 2014, Derek Jeter founded The Players’ Tribune, a website designed to allow players to tell their stories without a media filter — and communicate directly to the public without having to answer questions.

Governments, musicians and film celebrities have long blocked access from the public, but the nuisance of the open locker room left professional athletes late to the control party. LeBron James now has SpringHill Entertainment, his powerful production company. Kevin Durant has Thirty Five Ventures. Steph Curry has Unanimous Media. Carmelo Anthony has Krossover Entertainment. Malcolm Jenkins has one, Listen Up Media. A co-executive producer of “Blackballed,” the recently released documentary on the Donald Sterling-Los Angeles Clippers scandal, is — Chris Paul. The strategy is clear: Whether individual players or entire leagues, the powerful want to control the answers and the questions.

“The Last Dance” has been criticized for being an inside job, a Jordan-brand vehicle instead of independent documentary journalism, and it is true that heavy-hitting insiders combined to make the film possible. Along with Mike Tollin at Mandalay Sports Media, Jordan business partners Estee Portnoy and Curtis Polk served as executive producers. Polk is Jordan’s Charlotte Hornets co-owner. Portnoy is Jordan’s business and brand manager. Tollin and NBA commissioner Adam Silver have been close for decades. Mandalay chairman and CEO Peter Guber is a longtime powerhouse in the sports field and executive chairman of the Golden State Warriors, and he serves on the NBA board of governors. Jordan’s brand Jumpman paid prominent journalists to take over its live Twitter feed for the documentary with one stipulation: They were prohibited from criticizing Jordan, his teammates or anyone he played against.

Jordan and the NBA jointly own the footage of “The Last Dance” — footage the public likes to believe belongs to them, memories of what they witnessed on TV, or if they were lucky enough, saw in person. Whether it be from the White House, the basketball court or the commissioner’s offices, billionaires aim to control the media. Information is the target of privatization as surely as the post office, Social Security or your local trash pickup. The goal is to curb public accountability, what the public knows, to smother the constitutional, traditional expectation of a free press. All presidents have learned well the lessons of Watergate and Vietnam, and in the half-century since have manipulated media so completely they have virtually guaranteed the press never takes down an administration again.

The same is true of the NFL, NHL and MLB. All footage occurring within an arena of a professional sports team belongs to the league. If a fan who pays for a ticket at Staples Center shoots a 10-second cellphone video of Kawhi Leonard during warm-ups, the NBA owns that footage, even though those stadiums are funded by the public. Your tax dollars fund private property. They control what you see.

Tollin is insulted by the criticism that “The Last Dance” is propaganda. Jordan, he said, made no requests or demands of the filmmakers, had minimal questions and did not interfere with the editorial process. Jordan was interviewed three times at various properties in Florida for a total of eight hours, and altogether, Tollin said, they interviewed 105 other people — with a list three times as long. Tollin said the omissions — the lack of Jordan’s family, the dearth of dissenting voices, especially that of blackballed former teammate Craig Hodges — were not driven by Jordan. Tollin said Hodges was on their list, but the interview simply never materialized.

“We had a checklist: gambling, conspiracy theory about retirement, his father’s death, his lack of activism and his teammates,” Tollin told me. “I think we touched on all categories. From the start, we asked ourselves, ‘Is this a workplace drama or is it a domestic one?’ We both believed it was a workplace story, and [director] Jason [Hehir] and I shared a general disinterest of the wives and children of the lead characters. Michael is one of the most private people of our lifetimes. He’s glad this is over. He wants to get on with his regularly scheduled life. Michael never said you can’t talk to either of his wives. We didn’t feel doing so advanced the story.”

How to Watch

Every person should be entitled to their story, especially for a person as forensically dissected as Michael Jordan. I asked Joe Dumars, the Hall of Fame Pistons guard, why he wasn’t in the film. He told me the filmmakers reached out to him, but while he had enormous respect for Jordan and found it entertaining, the film was Michael’s show. His story, as he saw it.

In a sense, Tollin and the director, Jason Hehir, got lucky that Jordan was willing to be seen as openly as he was. “I think the film did much to demystify him,” Tollin said. “There were many times when it took a hard, unflattering look at him.” Watching Jordan was the singular power of the five weeks, fascinating but not always a compliment. He is not a gracious warrior. It also must be said that omitting Jordan’s family is a glaring hole, for home is an essential component to understanding a person in full dimension. Home should be the place where we are at our most human. Did he not talk to his wife at the time? How did she feel about Bill Laimbeer cheap-shotting her husband? Did she soothe him, give him life? Did he bring the game home, as Henry Aaron once told me no athlete should ever do? Or does Michael Jordan always stand alone?

“The Last Dance” is not propaganda, but it is a product of public space controlled by private interest. Privatization — the leagues as sole proprietors of the images we all witness, the players executively producing themselves — is not only the chilling future of filmmaking but its present. It is also America. Since 1970, public wealth in the United States has plummeted to almost nothing. Public lands are being privatized; try sitting in New York City’s Bryant Park — designated a public park in 1686 but privately managed since the 1980s — after midnight. Public journalism, uncontrolled by its subjects and its corporate partners, is on a ventilator. Like presidents, entertainers and sports leagues, athletes have decided that the best way to control their message is to control the medium. He does not aspire to be a filmmaker, but Michael Jordan spawned a new generation of athlete-as-mogul, branding their sneakers, now privatizing their voices. Off the court, LeBron James rarely appears on programming he doesn’t own. This generation has entered into the media space not to preserve public journalism but to destroy it, to not be questioned. Under such controls, that an often unflattering but authentically human picture of Jordan emerges is a victory — and a reminder of how government has failed to protect its citizens from private takeover of publicly financed facilities. Control is an essential component of empire.

REPUBLICANS, SHOES AND SO ON …

GE·O·POL·I·TICS

Noun

Politics, especially international relations, as influenced by geographical factors. — Merriam-Webster

In the 1990 U.S. Senate race in North Carolina, Jordan did not publicly endorse Harvey Gantt, a Black Democrat attempting to unseat Jesse Helms, a white Republican incumbent. It is, and forever will be, incorrect to view Jordan’s decision as a refusal to engage in politics. Jordan’s off-the-court legacy is very political: He is the non-military extension of the post-Cold War American Empire. Jordan spread American consumerism and cultural influence of underwear and soft drink, sneaker and hamburger sellers to the world without providing a voice at home for the Black people, his people, who largely and painfully comprise the empire’s underclass. The Berlin Wall fell in 1989. In 1990, McDonald’s opened its first restaurant in Russia. The Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. Jordan’s presence at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics as a McDonald’s pitchman did nearly as much for Big Macs globally as it did for basketball. Adidas and Puma owned the European sneaker markets before Barcelona. After, on the feet of Jordan, Nike was the choice of the coolest athlete in the globally growing, cool sport.

The influence of American capitalism and cultural dominance saturated the fledgling post-Soviet republics and the suddenly deregulated Russian economy. It is impossible to address the geopolitical impact of American culture in the final decade of the 20th century without seriously discussing the power of Michael Jordan. And far from omitting Jordan’s contribution to American cultural geopolitics, it is routinely celebrated, for empire is generally seen as his greatest accomplishment. According to Forbes, his net worth was $2.1 billion as of May, and he ranks No. 1,001 on Forbes’ list of the richest people in the world. He is America’s richest former athlete.

Jordan sold America, and America reveled in the great Black man as leading cultural export — softening the reality of what the nation was doing to its Black citizens. This selling of America is driven by politics, but the word political exists as a pejorative only when used as a stand-in for “Black people.” When discussing the popularity of basketball around the globe, the revenue it has generated, the countries that now enjoy robust basketball leagues and international programs, people readily and heartily credit Michael Jordan, basking in the afterglow of what he did for America’s standing in the world.

“In ’92, the NBA was in 80 countries, and now the NBA is in 215 countries,” the late commissioner David Stern said in Episode 10. “Anyone who understands the phenomenon of that historical arc will understand that Michael Jordan and his era played a tremendous part. He advanced us tremendously.”

Former President Barack Obama echoed Stern moments later. “He became an extraordinary ambassador, not just for basketball but for the United States overseas and part of American culture sweeping the globe. Michael Jordan and the Bulls changed the culture.”

While selling that America, however, Jordan also sent the message through his silence during the Helms-Gantt race: The millions of white people who did not care to hear his political advocacy were far more important to him than the millions of Black people who did. This was not a money choice, for Michael Jordan has never been in danger of losing any, but of choosing more money. Of choosing empire. Of choosing not to risk a single, ruthless cent — and of not choosing Black people. Michael Jordan could have sold American opportunity while making very clear the difficulties endured by Black people whose foothold in this country had always been tenuous — a fact he knows personally as well as anyone. Paul Robeson did it. Jackie Robinson did it. Rose Robinson did it. John Carlos did it. Bill Russell did it. Muhammad Ali did it. Michael Jordan chose not to.

It was Jordan’s choice to make, but do not tell me that a choice then was not being made — just as a choice now was made for Jordan to donate $100 million to fight racial inequality as America fractured and burned following George Floyd’s death, as unidentified secret soldiers occupied city streets. Fascinatingly, because he must always remain unimpeachable, always victorious, the empire still sells Jordan’s silence and his billions as an asset to the Black people living with nothing — this one-in-a-million talent as aspirational to them. He represents the payoff, the idea that you can survive the maze of dead ends and false promises that comprise the dead-or-in-jail narrative America loves so much when one of its favorite Black athletes survives and emerges a billionaire. This is usually done through lionizing the legendary Jordan work ethic, as if all that Black people needed — the ones who grew up as he did, where he did, and wound up carrion in America’s deadly wake — was not his genius or a system unbent on killing them, but his drive. This is the American fantasy and its favorite use for Michael Jordan: for his presence to remind Black people that they are solely responsible for their woeful place in this land. He made it. So could they, if only they worked as hard. It is the greatest insult of all.

FIN

Twenty-two years after the Bulls dynasty, Michael Jordan left a legacy of the athlete incarnate, the exemplar for those who worship obsession, dominance, empire and ruthlessness — not just for his sport but for all sports. He is the standard not of disposition but of results, for there have been many Jordan-like obsessives who scorched the earth, alienated contemporaries but did not win. He is at once an untouchable standard and cautionary symbol of the journey.

“The Last Dance” was not a celebration. It was not an invitation to share and reminisce, but a reiteration of domination — not over the Lakers, the Suns, Jazz, Sonics or Blazers, but over everyone, teammate or opponent, fan or writer, the unborn rivals to the throne, over anyone who’s ever thought about dribbling a basketball. Jordan is no different from the artists and generals, the Wall Streeters and scientists, and all of the other obsessives who push themselves to the point of insanity, and often beyond it, to complete the quest. He has captivated the world because of it. The film will stand for its moments of humanity and truth: Michael Jordan was willing to die to win, but he was also willing to destroy to win, and when seen through the lens of his isolation, loneliness, physical and mental exhaustion, the price of total victory has already killed off very important parts of himself, because even in total victory, this biggest man often looks so terribly small. Compassion, collaboration, friendship, the instinct to celebrate over dominate, these qualities were absent from “The Last Dance” because they were missing from him. They may be unimportant qualities worth ridicule in the theater of Game 7 competition, but Game 7 is long over, and they are now essential for Jordan’s second act, after the dance. As an owner, executive, colleague and mortal, he has appeared adrift, uncertain how to exist without empire — without the need to remind you of Michael Jordan’s place, without someone to beat. Without these qualities, looking backward at his conquered foes appears to be the only satisfying place for Michael Jordan to be.