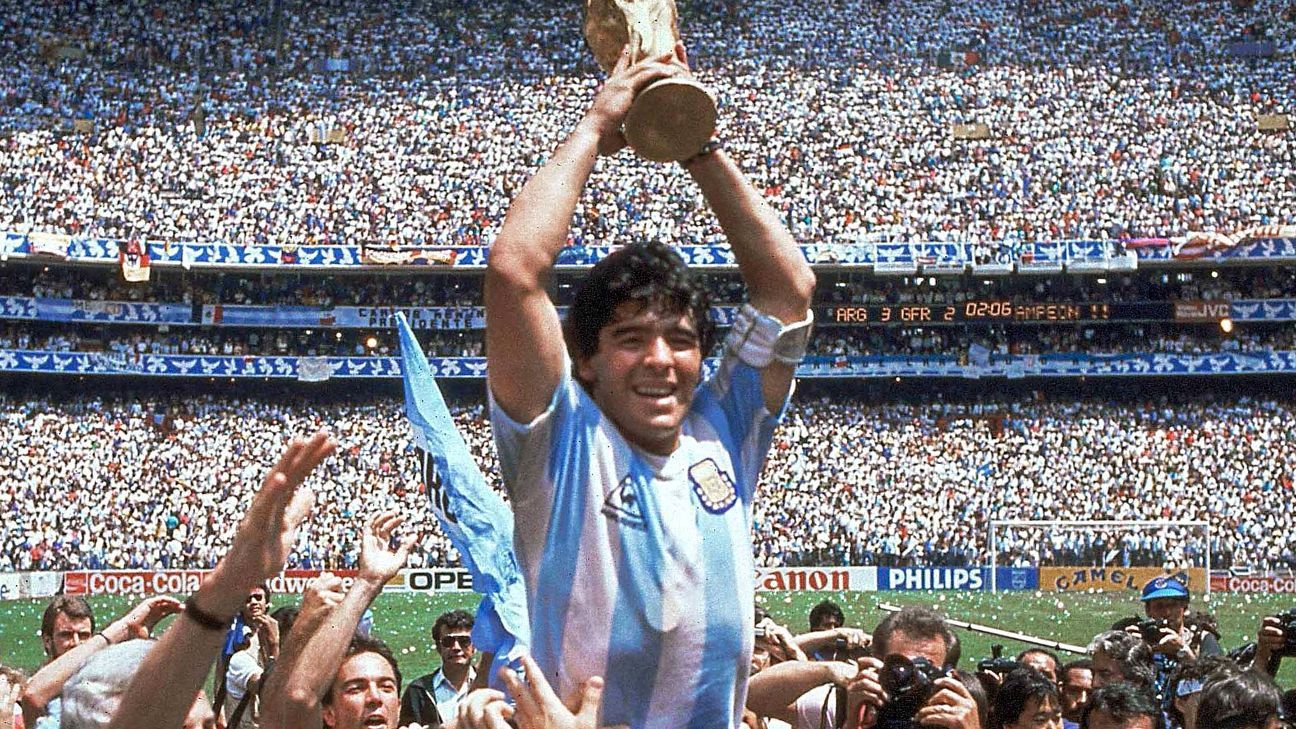

It was four minutes in a rich and fully lived life that spanned six decades, ending on Wednesday as news of the death of Diego Maradona filtered around the world. But, if you can begin to understand them, perhaps you’ll understand why Maradona meant so much to so many. And why, as Lionel Messi — his fellow Argentine and universal G.O.A.T. contender alongside Pele and Cristiano Ronaldo — put it, “He is gone, but he will be with us for eternity.”

– Report: Maradona dies at age 60

As massive as Maradona’s on-field legacy is — and it includes titles in three different countries, as well as captaining Argentina to victory in the 1986 World Cup — his charisma and resonance off the pitch might be even greater.

Those four minutes on June 22, 1986, in front of 114,500 souls at the Azteca — the “Hand of God” that guided the ball over the head of Peter Shilton and into the English net, followed by the 10-second, 60-yard dash forever known as the greatest World Cup goal of all time — encompassed the yin and yang of sports. They showed the craven, worldly drive to succeed at all costs (even by cheating, because that’s what it was) and the divine, celestial unimaginable skill that elevates star athletes, albeit briefly, into something superhuman.

But they went further than that. They fully reaffirmed the narrative of Maradona as Messiah, the people’s hero, the iconoclast both capable and willing to tear down the system. The fact that these goals came against England, the country that invented the game, that built an empire, that still — rightly or wrong — represents the very embodiment of the “Establishment” in the eyes of so many, is relevant too. So too is the fact that he got away with it, the fact that he metaphorically flipped England the bird and lifted the World Cup a few weeks later meant, to many, that a higher power truly was on his side.

Maradona, of course, fully embraced it. The underdog tale always suited him. He left Barcelona for Napoli in 1984 in a world-record transfer that left many tut-tutting. This was an impoverished city on the wrong side of the country’s north-south divide, this was a team that had never won a league title. It was “bread and circuses,” the art of feeding the masses an impossible dream and doing so at great expense.

Except Maradona made the impossible possible. He delivered two league titles to the city of Naples, beating out the wealthier blue bloods from northern Italy. And he didn’t do it quietly. No, sir: he did nothing quietly. He did it while immersing himself into the city and the fan base, railing against the powers-that-be when things didn’t go his way.

In that sense, Maradona was the eternal teenager. He spoke his mind, sometimes valiantly — taking stands against war and poverty — sometimes petulantly, happily playing the victim card when things didn’t go his way and, over the years, attacking everyone from Pele to FIFA, with wanton abandon.

Was he playing to a crowd? Sometimes, sure. But it’s not lost on anybody that he eventually made up with virtually all of his adversaries. He didn’t seek their forgiveness; he simply made it impossible for most to stay angry at him. The fact that to a man, virtually every player he has ever played with remembers him fondly, tells its own story. Yes, he was different, he trained when he wanted to, sometimes not training at all. But if you were close to him, you couldn’t resent him. You fed off his greatness.

2:13

Ale Moreno remembers Diego Maradona’s life and the impact his career has had on the footballing world.

He lived a life of excess, very much in the public eye. Stories of drugs, prostitution, paternity suits, evenings spent in hot tubs with mobsters — you’ve likely heard them all, and they’re probably all true. He sucked the marrow out of life. He ascended as high as you can without losing the surly bounds of Earth, and he also spent more time crawling in the gutter than most.

Maradona did it all, and what’s more, he paid for his transgressions. That moment at the Azteca was one of the few instances when he got away with something. Health issues (both emotional and physical), a sense that high-level football passed him by (witness his disastrous stint as Argentina manager at the 2010 World Cup), the realisation that his achievements on the field could never be matched by anything he did off it… he took all the blows.

You should leave comparisons with other G.O.A.T. candidates to the side. Different eras, different game. (For a start, he might have starred in the original viral video; if somebody attempted it today, you’d imagine it would be slicker and decidedly less organic.) But if you do get drawn into the most pointless of debates, please note that he achieved greatness on two different continents. Please note that he never received the protection from vicious fouls that are part of the game today. Please note that he played on cut-up, divot-heavy pitches, not the putting greens of modern soccer. Please note that there were limits on the number of foreigners each team could field, and therefore he never enjoyed the stellar supporting cast (or the cannon-fodder opposition) today’s stars enjoy. And please remind yourself of what he did to his body along the way.

2:04

1978 World Cup winner Mario Kempes shares his memories of teammate Diego Maradona.

In 1998, an hour before the World Cup final, I was with a group of 20 or 30 members of the media huddled around Pele in the bowels of the Stade de France. Pele, the only other G.O.A.T. candidate at the time — Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo were children back then — was holding court about the upcoming clash between Brazil and France. Suddenly, there was a commotion down the concourse. Within seconds, the media disappeared, racing away, cameras and notebooks in hand.

I, a young reporter at the time, was left with Pele and his media handlers.

“What’s going on?” Pele said.

“I think… I think Maradona has just arrived…” replied one of his aides.

Pele shook his head and smiled wryly.

One day, there might be another Pele or another Messi or another Ronaldo. One day, somebody might come along and do everything they’d done on the pitch, except do it better. But even if someone manages to emulate and surpass Maradona on the pitch, there is no way they will do it while emulating him off it. (And maybe that’s no bad thing.) It’s simply hard to imagine another Maradona. Ever.

There won’t be one. There can’t be one.

Maradona was at once what we dream of being and what we say we abhor, perhaps because we see it inside of us. He rode his strengths and he failed to tame his weaknesses. But maybe that’s precisely what made him human, balancing out his otherworldly genius and making him as human and fallible a sporting icon as you’ll find.