It is universal. It is unique.

It is stacked, adjusted and set. It is mocked, remocked and mocked again.

But unless you are one of the cooks in the proverbial football kitchen, you haven’t seen it. It is the stew that everyone in the NFL makes and whose recipe is hidden from anyone outside the family.

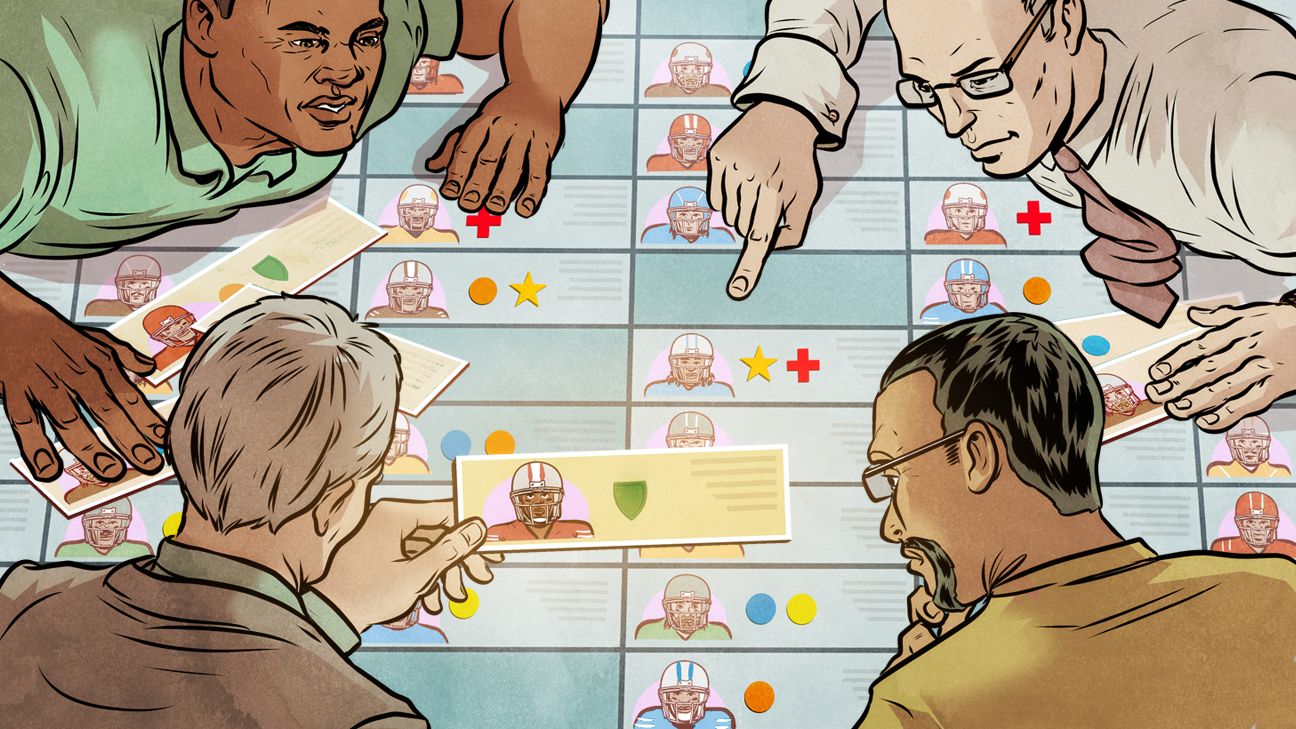

It is the NFL draft board, a place where player rankings are handed out, complete with concerns, questions and the sometimes tenuous hope of finding the league’s next big star.

And contrary to the notion of a “draft season,” the blueprint to each team’s draft weekend is a year in the making.

Yet how the NFL draft board is built, how it looks and what is on it — names, symbols, grades — isn’t really a topic for conversation outside the conference rooms or laptops where the boards are hidden.

How secretive is it? Just before the 2000 draft, when the Tennessee Titans had the 30th pick in the first round, then-Titans general manager Floyd Reese was asked who the 30th player on his board was, to which he replied, “Well, that’s one of my favorites, looking real hard there, that would be the guy between ‘None Of’ and ‘Your Damn Business.'”

To build the board, no one is above asking for guidance from myriad sources, be they human, data or spiritual.

“[Hall of Fame team executive] Ron Wolf would always let me put something on the draft board that was blessed by the pope,” said Bryan Broaddus, who worked in the scouting departments of the Eagles, Packers and Cowboys during his career. The item was something small enough it could fit in a plastic bag, but that had a papal blessing. “After the first year we did it, it was just kind of accepted after that. You’ll take all the help you can get and it went on the top of the board.

“Sometimes I would just sit there, in the room, with all those names and just wish, somehow, the future Hall of Famers would just light up, so then you would know. You just want to get it right.”

ESPN conducted dozens of interviews in recent weeks asking about the nuts and bolts of building a draft board. Those calls, combined with 35 years of reporting on many of those who grade the players and stack the boards, have helped shape an insider’s look at the process.

Each board is unique to its team and decision-makers, but one thing remains the same: The path to the draft is not a sprint after the calendar flips to February. It is a long, grueling, opinion-filled, argument-spiced marathon through an entire year.

The first meeting

The first step toward the next draft is often taken before the last piece of confetti from the previous draft has even drifted to the ground.

Former Titans scouting director Blake Beddingfield, who was in that position for 19 seasons, said the first meeting with the team scouts was almost always “the week after the draft, just before rookie camp.” Former Jets general manager and Dolphins executive VP of football operations Mike Tannenbaum said “about Memorial Day, every time.”

Some teams choose to go it alone, but most teams use either National Scouting — which runs the combine every year — or Blesto scouting services to help with their initial list of college football seniors as well as reports from their own scouts on players they may have seen in their campus visits.

That first list of players can be in the hundreds — some said as many as 900 names or more.

Scouts are often brought back to the team complex — in a non-pandemic year — in early June, around the team’s minicamp, to discuss the top prospects in each region heading into the college football season. From those meetings, the fall schedule for the area scouts — scouts who cover a specific geographical area of the country or specific conferences — will take shape.

Often the players are ranked for the first time at these meetings and those rankings are adjusted throughout the college football season as reports from the scouts come in and the scouting director evaluates each prospect’s grade after the visits.

The season

Denver Broncos general manager George Paton said the process of building a draft board includes “no shortcuts” and those involved have “to embrace the day-to-day … embrace the grind.”

Hundreds of plane tickets, thousands of highway miles, night after night in hotel rooms are on deck. It’s not uncommon for scouts to have hotel points in the millions.

The schedule will vary slightly from team to team and depends on the size of each scouting staff. But at the foundation during the college football season are the area scouts, who will each have to visit roughly five schools a week. A visit will entail a heavy dose of game video review and speaking with coaches as well as other support personnel about prospects.

At some of the larger college programs, these visits are limited and must be scheduled on specific dates during the season.

Knowledge is always power. Longtime scout C.O. Brocato, who died of cancer in 2015, would fill the trunk of his car with T-shirts, hats and other team gear from the Houston Oilers (and later the Titans) to give to staffers, security guards and receptionists at many of his campus stops. He knew their names, and an open door often followed a smile.

Known over a four-decade career to start his day at 2 a.m. in order to drive to stops across the vast expanse of Texas and the South, Bracato always joked that the first scout in “gets the clicker” to control the viewing of game video and “I like the clicker.”

After each visit, a scout may write a report for between eight to 12 players at the bigger schools, two or three at the smaller schools. Each week each scout sends those reports to the team’s scouting director.

The reports will include basic background, physical characteristics (height, weight and other general information like quickness or agility) and position-specific items such as how each prospect’s traits fit the position he plays and where he would fit in the team’s profile for that position.

It isn’t enough to say a player is good or bad. Details and specifics are coveted. Scouts who pay attention to detail and write meticulous reports quickly can be one of the most important aspects of a quality draft class.

Do the math: About five or six area scouts each sending between 40 to 60 player reports each week — it’s about 200 to 360 in all. Again the guidelines vary, but generally scouts have to visit schools with players who have draftable grades in their areas two or three times a season, with one of those three required to be a game day.

Some schools, smaller programs that may have one or two players with draftable grades in a given year, may be visited once, but area scouts will often circle back to those schools as well if they find they have a free afternoon.

Some positions, like quarterback and safety, may require more visits. Some teams will add a national scout — referred to as an “over the top” scout or “cross-checker” — or the college scouting director, the general manager or assistant general manager to the mix for more looks or “exposures” at a prospect, particularly on a game day.

“The challenge,” former Broncos general manager Ted Sundquist said, “is always staying organized, keeping the board up to date, making sure the reports are detailed and finding the spots where the scout’s grade and the scouting director’s grade may vary, things like that. But big or small school, you just don’t want to miss anybody.”

This year, with some players having opted out of the 2020 season due to COVID-19 concerns, there was a hearty review of 2019 game video, digging on player’s backgrounds and where they were working out, along with any added information from pro days or interviews with team officials.

A rainbow of symbols

It isn’t just football information in the scouting reports. Before the draft, the team’s medical staff is going to be involved, background checks are carried out and the elements of a prospect’s résumé off the field are added to the grade.

Teams use a variety of colors and symbols to note different issues about some prospects. Sometimes it is as simple as a red cross for an injury question or a yellow dot (proceed with caution, as one scout put it) for off-the-field issues, a green shield for effort questions, a skull and crossbones if a player has a difficult agent, or a star for a low test score.

In the end, players who stand out for the wrong reasons are referred to by some as “rainbow players” because they have so many symbols of different colors next to their names.

This will also vary from team to team. Some medical staffs will flag a player’s injury as a concern when others will not. Some general managers will be more comfortable with a player’s explanation of past trouble than others. A fight with a teammate, an arrest in high school, a failed drug test, a transfer to another school with a hazy backstory, an injury during a January workout — all of it is in the symbols.

As an example, last April several teams went into the draft concerned about the long-term impact of quarterback Tua Tagovailoa‘s hip injury suffered in his final season at Alabama. Tagovailoa, however, was selected fifth overall by the Miami Dolphins and is poised to be the Dolphins’ starter this season.

In 2019, Mississippi State’s Jeffery Simmons was not invited to the scouting combine despite being considered a potential first-round pick because a video from 2016 had surfaced of him punching a woman multiple times during an altercation the woman had with his sister. Simmons had also torn an ACL during a pre-draft workout.

Some teams had removed Simmons from consideration, but the Titans selected him with the 19th pick. Titans controlling owner Amy Adams Strunk said following the draft she had never been more involved in vetting a player before than with Simmons, including viewing the video with Titans coach Mike Vrabel and general manager Jon Robinson.

Simmons has started 22 games over the past two seasons with the Titans.

Beyond the symbols, how the boards look will vary. From the early days of chalkboards to electronic boards for some teams today, it’s always evolving and is often kept secret. But whether it’s a whiteboard or a magnetic board, names will be stacked in the order of their grades. That’s anywhere from 120 to 180 players for most teams.

It takes up the entire wall of a large conference room.

Then there are hundreds of names on another wall of the players the team graded, but who were removed from consideration because of questions, including injuries.

Teams augment this with the use of overhead projectors so they can display the same information from a laptop onto a wall as well. It allows them to move meetings from room to room and use the information about a particular player or particular position in smaller meetings.

It’s the rainbow of symbols, though, that often leads to some of the biggest differences of opinions among teams on top prospects. Those symbols explain why some teams will take a player off the board while others will select the same player in the first round. Many of those surveyed for this story said there is always an uncomfortable silence in draft rooms when a player who had been taken off the board is selected early, especially in the first two rounds. It’s “that we-better-be-right feeling” after the guy was picked somewhere else, “especially in the division,” as one scout said.

Last call for info

After the bowl games there are the all-star games and scouting combine — this year’s was canceled due to COVID-19 concerns — and then on-campus pro days and visits to the team complexes (in a non-COVID-19 year). At this point, the teams who feel good about their scouting staffs and the information they’ve gathered will have boards largely set.

The scouting director has spent months reviewing the weekly reports and game video and had hours’ worth of discussions with the scouts as the reports have come in. It means the notion of “risers” and “fallers” on the draft board, at least according to those who build the boards, is far less pronounced than it is often portrayed.

Beddingfield said “usually 80 to 85% or more of a guy’s grade came in the season” and Tannenbaum added “late information isn’t always great information; you have to be mindful of that.”

Teams will often adjust a prospect’s standing within his position group or within the round of the draft where graded. But most say it is rare for players to jump or drop, even one full round, let alone multiple rounds, because of Senior Bowl practices, a pro day or the combine.

This year will offer some slight differences due to opt-outs or canceled games because of COVID-19. A player such as Wisconsin-Whitewater offensive lineman Quinn Meinerz had his team’s season canceled due to the coronavirus, but he showed up to the Senior Bowl practices “looking like a different guy” than he had in 2019, according to one scout. Players like Meinerz may move around more on draft boards than in years past, but those big fluctuations will still be exceptions rather than the rule.

At times it can be a prospect’s performance in a workout or the practices at an all-star game can slightly tip the scales about what position that prospect may play. For example, before the 2020 scouting combine, some personnel executives wondered if Notre Dame wide receiver Chase Claypool would really be a receiving tight end because of his size (he was measured at 6-4¼ and weighed 238 pounds at that combine).

Then Claypool blistered the 40-yard dash in 4.42 seconds — among the fastest at any position of the players invited — to go with a 40 1/2-inch vertical jump and many in the league left Indianapolis thinking of Claypool as a wide receiver. The Pittsburgh Steelers selected him in the second round — 49th overall. Claypool finished his rookie year with 62 receptions, 879 yards and nine touchdowns.

Movement on the board after the college football season is far more subtle, subdued and nuanced within the tiered groupings than often perceived. The advent of pro days and combine workouts on TV — and so much more draft coverage overall than even a decade ago — have made the concept of movement on draft boards appear larger than it is inside team complexes.

A caveat is an arrest or a significant off-the-field issue that happens between the end of the college football season and the draft. It’s why teams have people in the scouting department monitoring social media throughout the draft process to try to avoid the surprise of a video that goes viral the morning of a draft.

“You confirm something you wanted another look at, get an answer to a particular thing you needed, whether that’s medical, something athletically, or an off-the-field thing you wanted an answer to,” one longtime personnel executive said. “You’ll move a guy some within his group, but jumping up from one group to the next or down multiple groups or multiple rounds, the teams that do that probably didn’t get enough information from the area scout during the year. Does it happen? Yes, but rarely is it a big, big move.”

Lock it in

When draft weekend arrives, the number of players on the board will vary team to team.

The list of players a team would draft — the board they’re working off during draft weekend — has often been called the “value board,” essentially the players each team really likes and would select because they fit the team’s position profiles and scheme.

As scouting staffs have grown and the process has become more refined, 300-player draft boards are largely gone. Most teams have between 125 and 150 names on the value board. And when those players are selected, by any team, the names are taken down.

If they’ve done the work correctly, when all the draft picks are made — some 240 or 250 picks or so including compensatory picks — a team might have just a handful of names remaining on a well-built value board. Those are the first choices to sign as undrafted rookies.

While it isn’t considered as common, there are teams and general managers who will work what some personnel executives have called a “short board,” which might have 75 to 95 names.

A shorter board may force teams to trade out of a round when they have no players graded to that round. If the team doesn’t trade out, it could find itself taking a player it didn’t have graded anywhere close to that round.

An example of an overreach can be found with the Broncos and the 2010 draft. Many with the team at the time said the Broncos used a short board approach that year — Josh McDaniels’ second season as coach — with fewer than 100 players on it. Among the players they selected was North Carolina tight end Richard Quinn in the second round (64th overall) — their third second-round pick. No other team contacted in the weeks after the draft had a grade above the seventh round on Quinn, who had 12 receptions during his career at North Carolina. Quinn said later his agent had told him not to expect to be drafted.

He played 30 NFL games with two teams and finished his career with one catch.

“Anybody who has worked the job would say, retrospectively, most any time we made changes late I wished we had not,” Tannenbaum said. “But that’s why it’s important to have good evaluators among your scouts who give you the information you need to make the best board you can make.”

The value board comprises the “best players available” who also fill needs, including those who would be the best specific scheme fits with the current coaching staff.

The remainder of players with draftable grades — but who might have symbols next to their name or do not fit into a team’s system — are listed on another board, or list, sometimes called the “back board” or the “out board” to monitor where they are chosen.

“And you try to kind of get a feel for how the board is going to go around the league, kind of work through all the scenarios with potential trades,” Broncos president of football operations John Elway said. “Just make sure you’re ready to adjust and move and feel good as an organization about your evaluations. And in the back of your mind you kind of know there is no predicting what everybody is going to do — the curveball is coming.”

Make the picks

Start with the draft’s dirty little secret about the first round. There are never, ever 32 first-round grades on draft boards throughout the league.

Want to know why teams bail out of the bottom of the first round so often? It’s because all of the players they had with first-round grades are gone. Or why a team quickly trades back into the No. 32 spot as the clock winds down? They want to snatch up the player still on their board with a first-round grade who has not been selected.

During dozens of interviews in recent weeks, the highest total given for first-round grades in any draft was 27 — and one general manager said “you knew that was going to be a damn good draft.” The lowest? Seventeen.

Beddingfield said scouts are among the most nervous and engaged on draft weekend. And emotional investment is the biggest reason. “I always battled for them to be in the room with everybody when we made the picks,” Beddingfield said. “Some GMs didn’t want that, but I made it a priority. You’re telling those guys their work is important when they’re in there and there is tremendous pride when after all those weeks, the team turns in a card for the pick with a guy you looked at from Day 1.”

All of the people asked about all of this — every single one — said the teams that “stick to the board” do the best in the draft year after year. The lure of the late nugget of information, a “gut feel” in the final hours, should be discussed and dissected to make sure the change is actually a good one.

It is important for a general manager to create an environment where the scouts and others will speak up. Often the didn’t-stick-to-the-board picks result because those who made the grades don’t feel they can stand up to those making the picks. “And you better be a good listener as a GM,” Tannenbaum said. “If you’re going to stray from the board, you better have a good reason why you didn’t think that way before and you better ask the guys who saw the player all season. And it should make you pause.”

The so-called “pounding the table” for prospects a scout or a coach likes has to largely take place weeks before the draft, not draft weekend. There are ties to be broken in the minutes before the picks when the arguments may get the loudest, but as one general manager put it “the ties better be between players you liked all the way through.”

And virtually all of those interviewed said they believed most people not involved in the process would be surprised by how much the grades, the boards and where players are valued can vary from team to team. One team’s potential steal is another team’s name removed from the board deemed to have no chance.

In 2009, the Raiders selected Ohio University safety Mike Mitchell with the 47th pick overall, a major surprise to most. ESPN’s Mel Kiper Jr. said he had a seventh-round grade on Mitchell, and some teams privately said they didn’t have him among their top 280 players.

Mitchell then fueled some of that skepticism when he started nine games in his first four seasons, though he would go on to play 10 seasons overall with five years as a regular starter.

“The board is players you like; other people may not, but you do,” is how one longtime personnel executive put it. “Sometimes you’re not right until a few years out and sometimes you’re not right until the guy goes somewhere else because they fit him better or he gets healthier or he just develops. Fit, the developmental curve, coaching, the guy’s work ethic, maturity, it all can add up differently and those are the questions you’re trying to answer when you make the picks.”

After the picks are made — or even as the seventh round gets underway — the scramble begins for the undrafted players. It is inevitable with so many opinions on so many players around the league, players with fifth-, sixth- or seventh-round grades are left on a board. Some draft boards will simply have a large red line to mark where the draftable grades stop; the group of players posted below it are that team’s priority free agents.

Scouts, assistant coaches, assistant general managers, general managers and head coaches acting as closers scramble to get the best of the rest signed as undrafted players.

“A seven-round draft, there are good football players who fit what you do still on the board after the picks are done if you’ve stacked it right, and they didn’t get picked just because of the way things fell,” Elway said. “We want to find guys who can be Denver Broncos wherever we have to find them.”

It’s why scouting is so important and why Elway often opened media gatherings after the draft each year by naming, and thanking, each of the team’s scouts and other scouting personnel.

“Those guys are on the road, and it gets lonely out there sometimes,” Elway has said. “They do a hell of a job and we ask a lot of them.”

Rinse, repeat

Beddingfield said rookie camp, usually in May, was always the last pit-of-the-stomach feeling for a scout moving from one draft to the next.

“You just didn’t want to go out at rookie camp and see a guy you really fought for struggle; you wanted him to get off to a good start,” Beddingfield said. “Crazy to think that way because he’s just getting started, but in that moment, in the back of your mind, it’s all those nights, all that road traveled, how much you like the kid. You just want it to look like it’s going to be great. And when he goes on to be great, there is nothing better. But you finish that camp and you hit the road again.”

Tannenbaum said: “Sometimes people would kind of say we made all those reports and we only took seven players. My response always was, ‘We just made the first report for our pro personnel department on the other guys. They go right to that database so you have it in September when they get cut or two Septembers from now.’ When it’s over, there’s relief, exhaustion and the 10-minute feel-good, that absence of agony that makes you feel so good. And then you start again.”