PULLMAN, Wash. — Washington State student Katie Lane stood on the field at Martin Stadium and tried to keep it together. The last time she attended a Cougars game, she was with her dad. Now, she was accepting an honor on his behalf on Oct. 16, just weeks after he died at 45 following a short battle with COVID-19.

Patrick Lane was the recipient of the Chosen Coug Award, given to a parent or family member who made a positive impact on their student’s WSU experience. Katie wrote the nomination essay on her phone while planning his funeral.

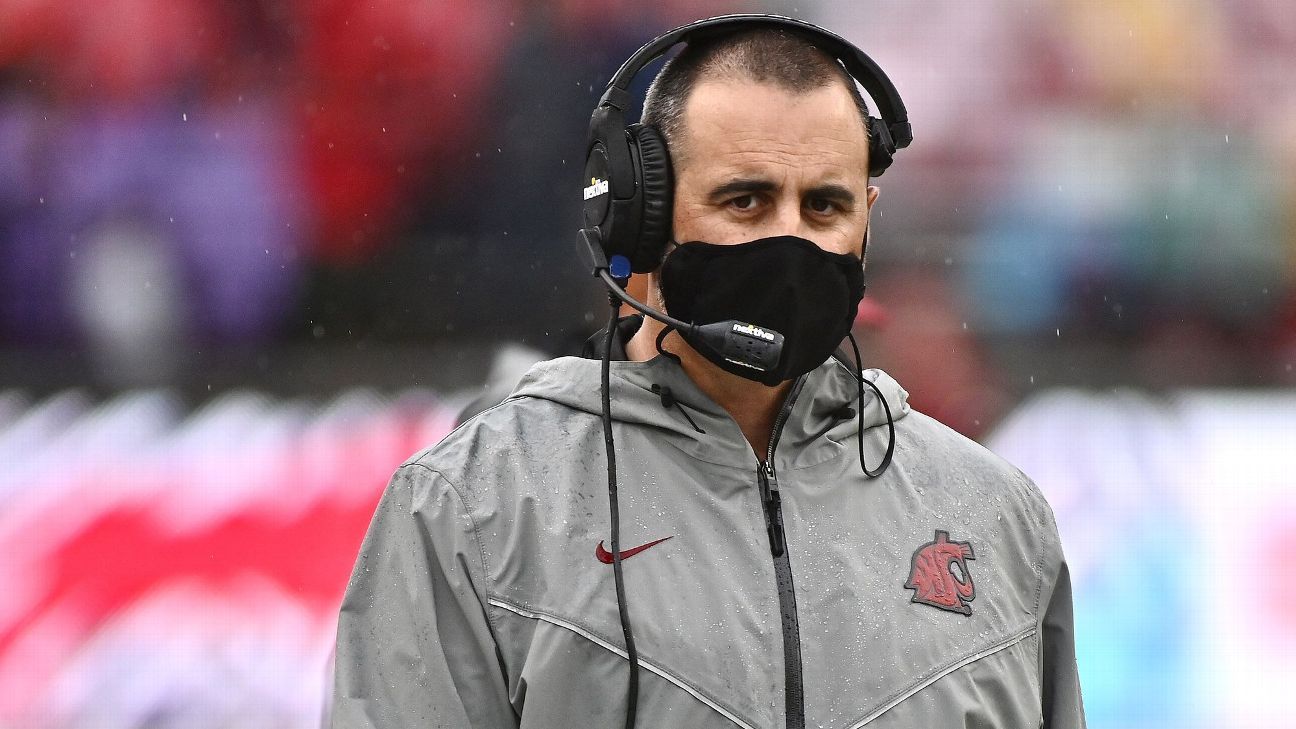

With Patrick’s parents watching from WSU president Kirk Schulz’s suite, the timing of the presentation wasn’t lost on Katie. She, like just about everyone in the stadium, knew that WSU coach Nick Rolovich — standing nearby on the sideline — faced an Oct. 18 deadline to become compliant with the state’s vaccine mandate or risk termination. Rolovich, the state’s highest-paid employee at roughly $3 million annually, was seeking a religious exemption to avoid getting vaccinated.

“I definitely got pretty emotional toward the end of the announcement just because I did start to realize like, ‘Oh my God, he’s right over there. He can hear what’s going on right now,'” Lane said of Rolovich. “But this isn’t going to change his mind, and that hurt because my dad was a healthy guy and he didn’t deserve to die — nobody deserves to die from this.”

The presentation took place during a short break in the second quarter during WSU’s game against Stanford. As words from Katie’s essay were read over the PA system, a picture of her with her dad was shown on the video board and the crowd was informed of how he died.

Like Rolovich, Patrick Lane was hesitant to get vaccinated. He wasn’t against vaccines, his daughter said, but despite pleas from her to get vaccinated, he told her he felt safest waiting for full approval from the Food and Drug Administration. The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine received full FDA approval on Aug. 23, three days after he had tested positive. On his deathbed, he told his wife via FaceTime he didn’t want to die and that he should have gotten vaccinated.

Katie Lane’s on-field moment may not have resonated broadly during an unprecedented week in Pullman, but it underscored the message the university wanted to send to the fans inside the stadium. For months, Rolovich’s unwillingness to get vaccinated sent the opposite message, which became a source of embarrassment for many faculty members.

Less than two hours after Lane’s presentation, the Cougars came back to beat Stanford 34-31 for their third straight victory. Players doused Rolovich in Gatorade, and those who spoke publicly made it clear they wanted him to stay.

Within two days, Rolovich and four unvaccinated assistants, Ricky Logo, John Richardson, Craig Stutzmann and Mark Weber, were fired. It was the resolution to a saga that has divided this college town — exemplified by Lane’s heartache and Rolovich’s Gatorade bath — since late July, when Rolovich was the only Pac-12 coach unable to appear in person at media day.

This is the story of those few months and especially the chaotic final days, including never-before-told details of the battle between Rolovich and Washington State over his vaccination status.

WASHINGTON STATE LEADERSHIP became aware of Rolovich’s hesitancy toward COVID vaccines in the spring and for months provided him access to its best resources to help inform his opinion.

On April 21, Rolovich was granted an audience with Dr. Guy Palmer, a world-renowned WSU regents professor of pathology and infectious diseases.

It had been about four months since the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines were both granted emergency-use authorization by the FDA, and athletic director Pat Chun arranged for the meeting to take place.

“As I am a member of the National Academy of Medicine and not affiliated with the athletic department, Pat thought Nick may be more trusting of the information and more comfortable with a dialogue where he could ask specific questions,” Palmer said.

Palmer completed a postdoctoral fellowship in vaccine immunology, leads disease control programs in Africa and Latin America and has been heavily involved in WSU’s COVID-19 testing program and vaccine rollout. He is considered one of the foremost experts on vaccines in the state of Washington.

Over about an hour, Rolovich drove a conversation that focused on topics that were consistent with what Palmer said has been shared by the “anti-vax crowd on social media” over the past several years.

“Kind of typical ones: Is Bill Gates involved with the vaccines? Does [Gates] hold a patent on the vaccines?” Palmer recalled to ESPN. “He asked whether SV40 is in the vaccines and whether that could be a dangerous thing. And the answer to that is no.”

SV40, also known as the simian virus 40, was found to have contaminated polio vaccines in the late 1950s and early 1960s. However, multiple studies — including one from the Institute of Medicine Immunization Safety Review Committee in 2002 — have not found a link between that contamination and any harmful impacts. No vaccines currently contain SV40, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and it’s unclear where Rolovich would have gotten the idea it was present in COVID vaccines.

(In a text message exchange with ESPN Tuesday evening, Rolovich described it as a “nice discussion with Dr Palmer” but declined to elaborate or be interviewed further.)

“I just tried to address those kind of more specific questions that have come up and I think many of those concerns were widely shared on social media, by individuals, and I just addressed them with the best data that I could and tried to give him clear answers,” Palmer said.

While Palmer left what he called “a very cordial conversation” unsure if Rolovich would get vaccinated, he felt the coach’s primary concerns were about possible side effects.

“I think it’s fair to say that was his major hesitancy,” Palmer said. (Rolovich did not bring up any religious beliefs he felt could be in conflict with taking a vaccine, Palmer said.)

Rolovich’s attorney, Brian Fahling, took issue with Palmer’s interpretation of the coach’s primary concerns.

“If that’s the inference that the doctor drew from his conversations with Nick, I would say he is fundamentally and inescapably wrong,” Fahling told ESPN Tuesday night. “He doesn’t know Nick. Nick is not going to go into his religious faith or his beliefs.”

Nine days after meeting with Rolovich, Palmer, who told ESPN the COVID vaccines are among the most studied and scrutinized in human history, spoke to a larger group of athletic department staffers. He discussed a wide range of topics related to vaccines from the basics to how doctors can be sure it doesn’t change someone’s genetic code and other misconceptions.

“There was a lot in the media about [how] this vaccine was developed in unprecedented time,” Palmer said. “That was a pretty common headline. It was rolled out in pretty much unprecedented time, but it wasn’t really developed in unprecedented time.

“So I tried to spend a little bit of time explaining that mRNA technology [used in the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines] is by no means new and what it actually does and doesn’t do.”

ON APRIL 28, WSU announced it was instituting a vaccine requirement for students and employees for the fall, though it was more of a strong advisory than a true requirement. The policy allowed exemptions for personal reasons — in addition to medical- and religious-based ones — which allowed the university time to explore the legality of a stricter mandate, according to WSU spokesperson Phil Weiler.

It didn’t become a public relations issue for the university until Rolovich tweeted on July 21 that he elected not to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. The announcement came in advance of Pac-12 media day on July 27, where a vaccine requirement was in place for all coaches and players in attendance. The 11 other Pac-12 head coaches were present, while WSU was represented by running back Max Borghi and linebacker Jahad Woods. Rolovich took part virtually and refused to address his reasoning for not getting a vaccine, the first of many opportunities he turned down over the next three months to provide context for his decision.

Both players at media day defended Rolovich, with Borghi telling ESPN, “People are going [wild], Coug fans. They just saw Coach Rolo’s decision and they don’t really know who he is as a guy. Obviously, it’s his own body, it’s his own choice. I don’t really know his medical or personal reasons for that. They don’t know how much he has done for the city and this team.”

The decision didn’t sit nearly as well among the faculty.

“I think what would have been the broadest response of the faculty is embarrassed for the university,” Palmer said. “Especially because they’ve launched a new medical school in the last several years. We’ve gotten medicine, nursing, pharmacy — you’re building out as a health sciences university, and then you have a high-profile individual sending a different message.

“I think what many people miss is not everyone can be vaccinated and we have vulnerable people within our population. We don’t know who they are,” he continued. “They’re in our midst. They don’t have a flashing light on their head and vaccinating around them is really critical.”

When the Supreme Court allowed a vaccine mandate at Indiana University to stand on Aug. 12, the state of Washington had the precedent it was looking for to become comfortable expanding a prior vaccine requirement proclamation to include all employees at institutions of higher education. On Aug. 18, Gov. Jay Inslee announced employees had until Oct. 18 to be fully vaccinated as a condition of employment.

“I plan on following the mandate,” Rolovich told reporters the next day. “For sure.”

He was asked repeatedly for weeks to clarify if that meant he would get vaccinated or apply for an exemption, but offered no further insight. That arrived when June Jones, his college coach at Hawai’i and a longtime mentor, told USA Today that Rolovich sought a religious exemption in an article published Oct. 9. Rolovich provided confirmation later that day.

While multiple assistant coaches were in line with Rolovich’s stance — and public support remained from several of the team’s best players despite their 93% vaccination rate — others within the athletic department couldn’t comprehend how he could justify going against the advice of medical experts with what was at stake, sources said. Multiple Washington State staff members who spoke to ESPN said they felt it was about politics to Rolovich.

The closest thing to an explanation from Rolovich came in a news release two days after he was fired, announcing forthcoming legal action against the university from Fahling.

“It is a tragic and damning commentary on our culture, and more specifically, on Chun, that Coach Rolovich has been derided, demonized, and ultimately fired from his job, merely for being devout in his Catholic faith,” the news release read.

No major religious denomination opposes COVID-19 vaccines, including the Roman Catholic Church, which has encouraged its followers — which include Chun — to get vaccinated. On the same day Inslee’s mandate was issued, Pope Francis said, “Getting vaccinated is a simple yet profound way to care for one another, especially the most vulnerable.”

A church’s official stance, however, has no bearing on what can be a sincerely held religious belief in the state of Washington, according to Charlotte Garden, an associate law professor at the Seattle University School of Law and an expert in employment law. Rolovich would have needed to share examples of how his belief system was applied in other areas of his life as part of the exemption request process, according to the school’s website.

As of Thursday, the WSU system had granted 340 of 436 religious exemption requests for the five physical campuses, while 36 were denied and 60 were still being processed, according to Weiler. In a news conference, neither Chun nor Schulz, were explicit on whether Rolovich’s religious exemption was denied, though Fahling’s news release said it was.

By failing to adhere to the vaccine mandate, WSU likely determined he was in violation of Section 1.2.1 of his contract which states he will “comply with and support all rules, regulations, policies, and decisions established or issued by the University.” Chun said Rolovich was fired for cause and would no longer be paid.

Fahling, who also represents Logo, Richardson and Stutzman, was unwilling to provide insight into his forthcoming legal strategy.

“I can tell you that from a legal standpoint, we’re on very strong grounds,” Fahling said. “From a factual standpoint, we’re on extremely strong ground.”

Before proceeding with a lawsuit, Rolovich and the assistant coaches will need to exhaust an appeals process with the university as laid out in their contracts. Those appeals must be filed by Nov. 2. Fahling said the three assistant coaches he represents also had religious exemption requests denied.

Garden provided some insight into how Fahling might proceed from a legal standpoint.

“[They] could argue [Rolovich] has a constitutional right [under either the federal or the state constitution] to a religious accommodation, and that the constitutional right to an accommodation applies even where the accommodation would either impair Rolovich’s ability to do his job or increase the risk that others would get sick,” Garden said in an email. “This would require courts to break some new ground.

“One reason courts might not be willing to do that in this case is that Rolovich is a public employee — that matters because in other First Amendment contexts, the Supreme Court has said that government has more leeway to impose work rules on its own employees than it does to regulate the general public.”

BY THE TIME it was announced that Rolovich had been dismissed at 5:37 p.m. PT, on Oct. 18, the team had been informed and the news had been widely reported.

Shortly after Chun spoke to the team, Jake Dickert, the defensive coordinator who was named acting head coach, led a defensive walk-through at the practice fields adjacent to the football operations building. As players left the field, nearly all of them had their eyes trained on their phones, monitoring reaction and replying to messages about what had transpired.

“It’s not like it was a shock to us completely. We knew the mandate was going into effect and it’s been in the media,” defensive lineman Dallas Hobbs told ESPN. “Coach Rolo is a great players’ coach, so it’s hard to see him go. But we’ve got other people here and on staff that will step up. We’ve been through a lot, and we know how to push through hard times. It’s just another [unfortunate] thing we’ve got to get through.”

Though Rolovich said in the news conference after the Stanford game that he expected to remain the coach, in private he wasn’t so sure. According to multiple sources, Rolovich had indicated to staff members he thought it would likely be his final game.

With Rolovich’s knowledge, contingency planning for staff changes started weeks before and Dickert emerged as the most logical in-house option to take over. Part of that had to do with the potential for added stress on offensive coordinator Brian Smith, as Rolovich, Stutzman and Weber all coached on the offensive side, and Chun was comforted by the affinity the players had for Dickert.

“I would argue Nick was the head coach, the offensive coordinator, the quarterback coach and the chief culture officer of Washington State football,” Chun told ESPN. “That is a person who won’t be replaced and there’s no ifs, ands or buts about it. Jake knows that and I think all of our coaches know that.”

As difficult as it was for the university, the week following Rolovich’s firing proved successful on the fundraising front. The athletic department received $3.5 million in donation pledges, according to an athletic department spokesperson.

While it’s hard to quantify the divide among the fan base, Rolovich’s dismissal generated strong reactions from many on social media both in favor and against how things played out. Regardless, it’s clear the players’ college experience became collateral damage. In their own social media posts, multiple players expressed a desire to move forward and urged fans to direct their energy toward supporting the team.

Dickert’s public message was similar.

“I know sometimes people are mad, but if you’re mad, I hope you’re so mad, you’re willing to help us support our players,” he said last week. “And if you think today’s a day for celebration, I hope you’re going to show up [against BYU] and celebrate for our guys.”

It wasn’t until Friday that the school could officially announce that veteran run ‘n’ shoot coaches Dan Morrison (quarterbacks) and Dennis McKnight (offensive line) had joined the staff, though both men were able to observe practice earlier in the week (neither was permitted to coach during the week due to NCAA rules).

Their familiarity with the offensive scheme was important and so were their personal connections to Rolovich, which the players could relate to. When Rolovich arrived at Hawai’i as a quarterback in 2000, Morrison (quarterbacks) and McKnight (special teams) were both on the staff, and Morrison had long remained a mentor figure. McKnight delivered a message that seemed to resonate with the players, a source told ESPN.

They weren’t there to replace Rolovich, McKnight told the team. They were there to help the players make the most of the season and help them advance through a difficult situation.

Before a sparse crowd of 22,500 people, WSU started Saturday’s game against BYU about as well as it could have. Borghi capped an impressive opening drive with an 11-yard touchdown, but WSU would have trouble containing running back Tyler Allgeier in a 21-19 loss.

But the game was mostly about moving forward following a difficult week.

“Teamwise, I think it was good to have everyone together and it certainly helps me personally. I have my own things I deal with and that I’m dealing with currently,” said senior offensive lineman Abe Lucas, who wore a black-and-white shirt with the words “Freedom of Choice” atop an American flag in the Zoom news conference. “Being in a routine certainly helps ease the pain and the pressure that we all individually feel, especially with the events that transpired this week.”

At its best, a football team can be a unifying force on a university campus — a source of pride and a symbol of the community. For the past several months in Pullman, where the streets are lined with the WSU logo, the Rolovich standoff tested that unifying theory.

The best way to move forward is simple, according to Katie Lane, still grieving the loss of her father: “I want people to have more empathy.”

ESPN’s Dan Murphy contributed to this story.