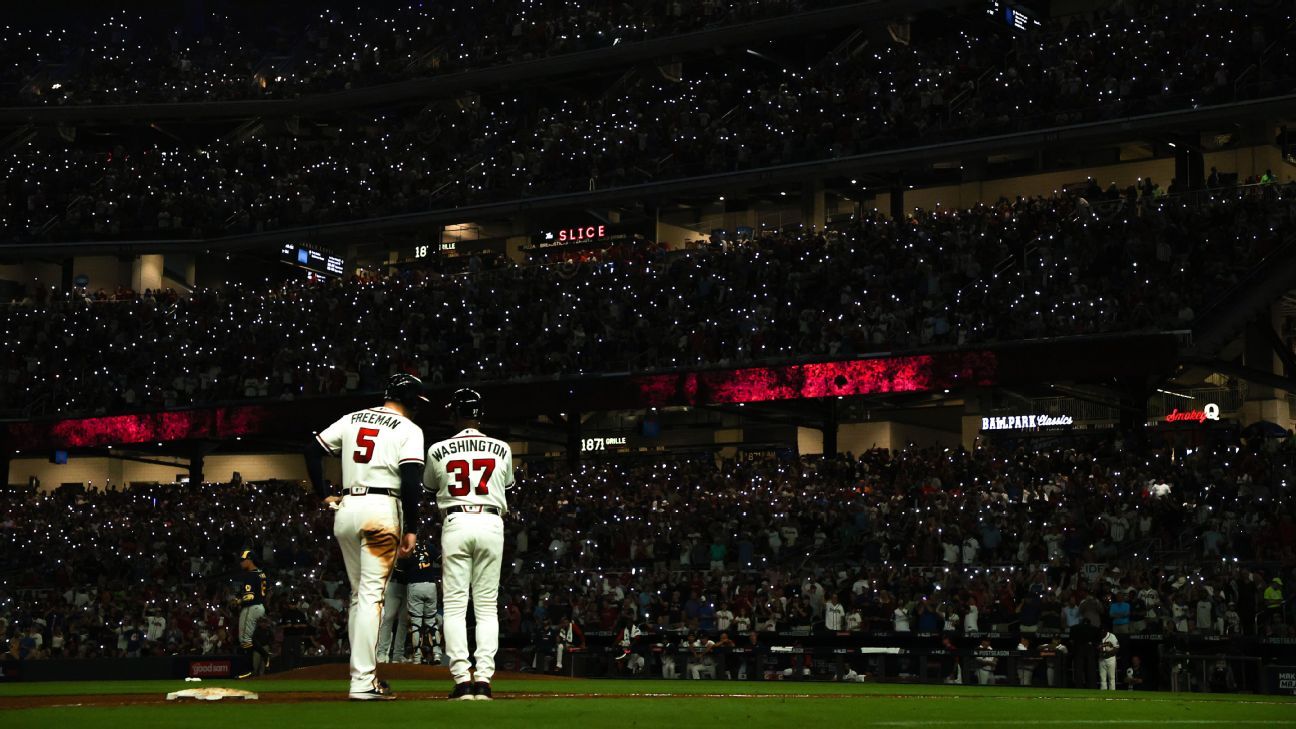

ATLANTA — Each of the next three days, a baseball stadium will dim its lights, thousands of people will illuminate the flashlights on their phones and they will engage in a wildly ahistorical, fundamentally problematic and altogether unnecessary ritual. The tomahawk chop, rubber-stamped earlier this week by the commissioner of baseball, will be broadcast on screens across the United States and around the world, and it will serve as a reminder that for all the progress made in eradicating unnecessary American Indian symbolism, it remains deeply embedded in sports.

On Tuesday, Major League Baseball delivered a weak, mealy-mouthed affirmation of the chop, a staple at Atlanta Braves games, which relied on canyon-sized gaps of logic and epitomized the tail wagging the dog. And as Truist Park hosts the Braves and Houston Astros in Games 3, 4 and 5 of the World Series this weekend, a vast-majority-white crowd will pack a stadium in the middle of the suburbs, bend their arms 90 degrees from vertical to horizontal and scream in defiance of those who see it for what it is.

Which is, of course, something destined to go away, like the former Washington Football Team name, the Chief Wahoo logo and countless other examples of Native American imagery in sports. It’s what made the position of the commissioner, Rob Manfred, so perplexing. To see him try to explain why MLB was backing the chop was to see an anthropomorphic pretzel twisting itself in real time.

“It depends on the way the community perceives the gesture, and in Atlanta they’ve done a great job with the Native Americans,” Manfred said. “I think the Native American community is the most important group to decide whether it’s appropriate or not, and they have been unwaveringly supportive.”

Manfred was referring to the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, a North Carolina-based tribe with whom the Braves say over the past year and a half they’ve “developed a cultural working relationship … that has resulted in meaningful action.” That action included an EBCI Night on July 17 and the creation of a Native American Working Group.

It also included a complete about-face by the chief of the Eastern Band. This week, Richard Sneed told the Associated Press: “I’m not offended by somebody waving their arm at a sports game.” He went on to say that the chop is “the least of our problems,” compared to crime and poverty in the indigenous community, as if getting rid of the chop and obviously deeper, more important issues are somehow mutually exclusive. This was the same Richard Sneed who, when asked by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution about the chop in October 2019, before developing a more robust partnership with the Braves, said: “That’s just so stereotypical, like old-school Hollywood.

“Come on, guys. It’s 2020. Let’s move on. Find something else.”

Unwavering, huh?

Even if we were to accept Manfred’s supposition that local tribes approved of the chop, the notion that only tribes within a three-hour radius of Atlanta are worth listening to is specious when the game is being broadcast to a national audience. Two years ago, longtime Muscogee (Creek) Nation chief James R. Floyd said the chant “reduces Native Americans to a caricature.”

Floyd’s voice is important, even though he’s not part of a nearby tribe, because once upon a time he would’ve been. There are 574 federally recognized indigenous tribes. None exist in Georgia. A particularly loathsome part of the Braves’ insistence on keeping the chop and the league’s support is the repugnant treatment of American Indians in Georgia. Thousands of Creek had their land in Georgia stolen during the early 1830s. Five years later, more than 16,000 Cherokee were forcibly removed from Georgia and banished to the Trail of Tears, the nine-state, 1,200-mile walk to their new land in Oklahoma. Thousands died.

One tribe in Wisconsin, the Forest County Potawatomi, owns a casino in the greater Milwaukee area. For years, the tribe has had signage on the left-field wall at American Family Field to market its casino — except for when the Braves or Cleveland Indians came to town, as Atlanta did in this year’s division series. The advertisement, which adorned the wall for the Brewers‘ 11 home series prior to the NLDS, was nowhere to be seen.

“The issue of Native American words and symbols being used as team names or mascots is an issue many tribes have advocated against for years,” the Potawatomi said in a statement to the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel in 2018. “As a business owned and operated by a tribal government, this is a decision we’ve made to support and build on that advocacy.”

If it’s not the Cherokee then it’s the Creek, and if it’s not the Creek then it’s the Potawatomi, and if it’s not the Potawatomi then it’s the National Congress of American Indians, which, in a statement on Wednesday, called on Fox, the World Series broadcaster, “to refrain from showing the ‘tomahawk chop’ when it is performed during the nationally televised World Series games in Atlanta.”

Before anyone chalks this up to a mob or cancel culture, perhaps take a look at MLB’s own social justice website, which includes a guide to “having conversations about race.” The first two bullet points:

Lead with empathy.

Listen and acknowledge responses and feelings.

Six months ago, MLB practiced those principles when it yanked the All-Star Game from Atlanta over the Braves’ vociferous disagreement after the backlash against more restrictive voting laws in Georgia. It did the same in a leaguewide embrace of the Black Lives Matter movement on Opening Day 2020. Despite Manfred’s desired goal to remain “apolitical,” the league, in certain instances, is not afraid to get political.

It has never been willing to do so on this issue in Atlanta. And so the chop continues to exist only because it started in 1991 and coincided with a glorious part of the franchise’s history, the boom decade in which the Braves won a championship and started a run of 14 consecutive division titles. To its adherents, it’s an heirloom of that time, something they’ve romanticized. Believing something is normal does not make it normal. Longevity and righteousness do not necessarily run parallel paths. Often, the opposite: Both are tried-and-true formulas to let problems metastasize.

And that’s what’s happening this week. The Braves haven’t been to the World Series since 1999. The world has changed. Indigenous people can use the social media bullhorn to amplify their perspectives. The Cleveland Guardians, remember, were the Cleveland Indians until a month ago. Years of pressure mounted, Cleveland recognized the necessity of a name change, and thus began a transformation that everyone will grow used to sooner than later.

We know this because we’ve seen it. For decades, the Braves employed an American Indian mascot named Chief Noc-A-Homa. He wore a headdress and danced on the pitcher’s mound and huddled in a teepee and celebrated home runs with smoke signals and breathed fire. In 1985, he also missed three events for the team and admitted to hitting on multiple women on the job. Rather than recast the role after the employee was fired, the Braves retired the character.

More than 35 years ago, the Atlanta Braves recognized something was wrong and remedied it. The refusal to do so now registers oddly, like a cocktail of hubris and cowardice. In 1985, the team was willing to guide fans to the right place. Now it isn’t, and MLB apparently refuses to mandate it.

It’s an inevitability the chop goes away, just like it will go away at Kansas City Chiefs games, just like it will go away, eventually and probably last, at the place it started, Florida State University, where the Seminole tribe offers its blessing for chopping at Doak Campbell Stadium.

Until that happens, teams will peddle the same vacuous arguments the Washington Football Team did before it dropped its former name, and fans will treat their right to participate in a chant or use a nickname as if it’s something important while turning a blind eye to the actual problems in indigenous communities, where poverty and violence against women and poor education leave Native Americans terminally vulnerable.

The most frustrating thing about the chop is how easy it would be to stop. It would be a small gesture. It wouldn’t fix any of those generational problems that affect American Indians. But it would, to plenty, return at least a modicum of dignity to a people that have already had so much taken from them.

When that eventually happens, we know the journey that Braves fans will undertake, because we’ve seen it before. First, denial and anger. They’ll bargain, they’ll feel depressed and eventually they’ll accept it, because fans don’t go to games just to chop. They go to watch the team they love, chop or no chop, and anyone who loves chopping more than Ronald Acuña Jr., Freddie Freeman and Ozzie Albies clearly has bad taste anyway.

It’s what made Manfred’s tack on Tuesday so stunning. He’s had 30 years to figure out the right thing to say about the chop, and his central theses were: Teams make their own choices (even though they actually don’t) and American Indians in the region are fully backing the chop (even though they certainly haven’t).

“The Native American community in that region is wholly supportive of the Braves’ program, including the chop,” Manfred said. “For me, that’s kind of the end of the story.”

Wholly supportive. Sounds about as convincing as unwaveringly supportive.

At least Manfred was telling the truth about one thing. The end of the story is coming. That noise you hear this week emanating from Truist Park will sound like the tomahawk chop, but in reality it will mark the beginning of its death rattle. The chop is not long for Atlanta, and, with any luck, not long for the sporting world.

Come on, guys. It’s 2021. Let’s move on. Find something else.