ESPN recently released its ranking of the 100 greatest baseball of all time, and there is one player who is distinct from the others on the list: Sandy Koufax. With the exception of the still-active Mike Trout and Bryce Harper, the others all enjoyed careers of both dominance and longevity. Koufax, however, packed almost all of his greatness into an extraordinary five-year run from 1962 to 1966, when he won 111 games, five ERA titles, three Cy Young Awards and two World Series. Just over 79% of his career value came in those five seasons, and even though he threw his last pitch 56 years ago, that peak was enough to rank Koufax No. 32 on our list and make him a first-ballot Hall of Famer.

With the recent Hall of Fame voting results in mind as well, I thought it would be fun to select what we’ll call the All-Sandy Koufax Team: players who packed most of their career value into a five-year peak of excellence (and note that for five-year peak, we’re considering a player’s five best overall seasons via Baseball-Reference WAR, not necessarily five consecutive seasons). To make our team even more interesting, for each position we’ll list one non-Hall of Famer and one similar Hall of Famer. The Hall of Fame generally rewards longevity over peak, but maybe some of these guys deserve stronger Hall of Fame consideration.

CATCHER

Non-Hall of Famer: Buster Posey

Career WAR: 44.9 (16th among catchers)

Five-year peak: 28.8 (8th)

64.1% of career value in five best seasons

When Posey announced his retirement in November, the general belief was that his next stop would be Cooperstown — maybe not a first-ballot selection, but soon enough given his peak performance and all the intangibles he brought in helping the Giants win three World Series. Not so fast. Posey’s career is similar to Thurman Munson’s — 46.1 WAR, a five-year peak of 29.5, an MVP winner and intangibles that helped the Yankees win two World Series — and Munson hasn’t come close to election. He peaked at 15% in the voting in his first season and never topped 10% after that. He received fewer than four votes when he appeared on the Modern Baseball Era Committee ballot in 2020 (12 of 16 needed for enshrinement).

Posey does have a couple advantages over Munson: His adjusted offense is better, with a 129 OPS+ compared to 116 for Munson, plus he was viewed as the best catcher in the game at his best (with competition from Yadier Molina) while Munson was clearly No. 2 behind Johnny Bench or even No. 3 or 4 behind Bench, Carlton Fisk and Ted Simmons. The depth at catcher was weaker in the 2010s than the 1970s and that shapes how we view Posey.

Hall of Famer: Roy Campanella

Career WAR: 35.6 (28th)

Five-year peak: 28.2 (11th)

79.2% of career value in five best seasons

Campanella’s MLB career was short since he was 26 before he debuted with the Brooklyn Dodgers due to segregation. Then he suffered a tragic car accident that ended his playing days at 35 (although hand injuries had cut into his offensive production in the two seasons prior). Campanella had three seasons where he hit .300 with power — .325 with 33 home runs in 1951, .312 with 41 home runs in 1953 and .318 with 32 home runs in 1955 — and combined with his leadership and defense, he won the NL MVP Award all three seasons (only the 1955 vote, when he edged out teammate Duke Snider was close). He also had seasons where he hit .207 and .219. Still, if anything, WAR underestimates his value, and I would certainly rank him much higher among catchers in five-year peak.

What might have been: Elston Howard signed with the Yankees out of the Negro Leagues when he was 21, lost two full seasons while in the Army and then was stuck behind Yogi Berra when he finally reached the majors at 26, forcing him to play left field to get at-bats. When he replaced Berra as the starting catcher in 1961, he was already 32 years old. He hit .348 and then won an MVP Award in 1963 (and finished third in 1964). It’s not hard to envision another path where Howard ends up in the Hall of Fame.

FIRST BASE

Non-Hall of Famer: Todd Helton

Career WAR: 61.8 (18th among first basemen)

Five-year peak: 37.6 (4th)

60.8% of career value in five best seasons

This little exercise has caused me to reconsider my own opinion of Helton’s Hall of Fame case. I viewed him as a classic borderline case, probably just on the outside, with not quite enough career value outside his peak and docking him for his Coors Field-inflated numbers. But now I realize his peak was so dominant that I would vote for him. He ranks behind only Lou Gehrig, Albert Pujols and Jimmie Foxx in five-year peak (although there is a sizable gap from Foxx to Helton) and behind only those three and George Sisler in three-year peak. Even better, Helton’s five-year peak runs over five consecutive seasons: From 2000 to 2004 he hit .349/.450/.643, with a top value of 8.9 WAR in 2000, when he hit .372 with an absurd 103 extra-base hits. He received 52.0% of the vote in this year’s election and continues to trend upward.

Hall of Famer: George Sisler

Career WAR: 54.8 (27th)

Five-year peak: 37.2 (5th)

67.9% of career value in five best seasons

Like Helton, Sisler was a slick-fielding left-handed batter who benefitted from his home park. He hit .356 at home in his career, mostly at Sportsman’s Park for the St. Louis Browns, and .324 on the road. Like Helton, an injury would eat away at his production. In Helton’s case, it was back problems. Sisler, who hit .407 in 1920 (9.8 WAR) and .420 in 1922 (8.7 WAR), missed the entire 1923 season with a sinus infection that affected his optic nerve, plaguing him with headaches and double vision. He returned in 1924, but was never the same player (he hit .320 over his final seven seasons, but his OPS+ was actually below league average). Bill James called him “perhaps the most overrated player in baseball history,” but he was a popular one and was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1939 as a member of the fourth class.

What might have been: Don Mattingly finished with 42.4 career WAR as back problems ate away at his power and longevity. Surprisingly, his five-year peak ranks just 28th among first basemen/DHs and his three-year peak tied for 24th. As good as he was, he didn’t post high enough OBPs to rank among the elite of the elite. Still, if he had stayed healthy, no doubt that 3,000 hits and Cooperstown would have been in his future.

SECOND BASE

Non-Hall of Famer: Chase Utley

Career WAR: 64.5 (14th among second basemen)

Five-year peak: 39.6 (7th)

61.4% of career value in five best seasons

Utley’s career WAR is higher than Helton’s, but I suspect his Hall of Fame case depends even more on how voters weigh his five-year peak given Helton’s more impressive career totals in hits, home runs and RBIs. From 2005 to 2009, Utley averaged 7.9 WAR per season, second only to Albert Pujols in that span, and more than five WAR ahead of Alex Rodriguez, the No. 3 player. Will that be enough dominance for a player who didn’t even reach 2,000 career hits? Utley’s five-year peak tops Hall of Fame selections like Ryne Sandberg (36.6), Roberto Alomar (33.0) and Craig Biggio (32.8) and makes him a stronger candidate than his counting numbers suggest. Since I’m pro-peak, I’m leaning pro-Utley for the Hall of Fame.

Hall of Famer: Joe Gordon

Career WAR: 55.8 (18th)

Five-year peak: 33.5 (13th)

60.0% of career value in five best seasons

Gordon was a nine-time All-Star with the Yankees and Indians and the 1940 AL MVP, but he played just 11 seasons, missing two during World War II. He played his final season at age 35 (he played two more seasons for Sacramento in the Pacific Coast League as player/manager, leading the PCL in home runs and RBIs in 1951). Career totals: Gordon 253 home runs, 975 RBIs; Utley 259 home runs, 1025 RBIs. Gordon never received much support on the BBWAA ballot and finally made the Hall of Fame in 2009 via the Veterans Committee. It’s possible that Utley also ends up going that route.

What might have been: From ages 23 to 26, Edgardo Alfonzo hit .305/.389/.477 and had seasons of 6.2, 6.0 and 6.4 WAR for the Mets. Some considered him the best all-around second baseman in the game — better than Roberto Alomar or Craig Biggio or Jeff Kent. He then injured his back in 2001 and had other injury issues the rest of his career.

THIRD BASE

Non-Hall of Famer: Dick Allen

Career WAR: 58.7 (16th among third basemen)

Five-year peak: 36.7 (7th)

62.5% of career value in five best seasons

Allen actually played a few more games at first base than third, but five of his six best seasons came when third base was his primary position. He had a tremendous peak as a hitter, leading his league three times in OPS+ while batting .300 seven times and hitting the baseball harder than most humans ever have. Allen just appeared on the Golden Days era ballot and missed election by one vote after previously falling one vote short in 2015 as well. His career OPS+ of 156 is the same as Frank Thomas’ and higher than Henry Aaron’s, to put his hitting prowess in perspective (granted, in a shorter career). He is also one of the most controversial players in MLB history, but at this point his Hall of Fame selection appears inevitable. Unfortunately, he died in 2020, and the Golden Days ballot won’t come up again until December of 2026.

Hall of Famer: Frank “Home Run” Baker

Career WAR: 62.8 (12th)

Five-year peak: 36.7 (7th)

58.4% of career value in five best seasons

One of the biggest stars of the deadball era, Baker, like Allen, was a feared slugger — although in his day it meant leading the league with totals of 12, 11 and 10 home runs. Baker missed two full seasons, otherwise his career WAR would be much higher. He missed the 1915 season, in the prime of his career, due to a salary dispute with Connie Mack, electing to work on his farm in Maryland and play with local town teams (imagine playing in your local softball league and having, say, Vladimir Guerrero Jr. coming up to the plate). Mack sold Baker’s contract to the Yankees, but Baker wasn’t the same dominant force when he returned in 1916. He then missed the 1920 season after his wife died, and he was left with two small children. He returned to play two more seasons and made the Hall of Fame in 1955.

What might have been: Al Rosen’s 1953 season with Cleveland is arguably the greatest ever by a third baseman: .336/.422/.613, 45 HRs, 145 RBIs. 10.1 WAR. He led the AL in home runs, RBIs, runs and slugging percentage and was the unanimous MVP choice. That WAR total is best for a third baseman in major league history. Rosen’s first season as a regular didn’t come until he was 26 in 1950; he was in the Army, and then he was trapped behind Ken Keltner, spending two seasons in Triple-A. He came up and had five straight 100-RBI seasons before back problems forced early retirement at 32.

SHORTSTOP

Non-Hall of Famer: Nomar Garciaparra

Career WAR: 44.3 (32nd among shortstops)

Five-year peak: 34.9 (9th)

77.9% of career value in five best seasons

With the emphasis on career value in Hall of Fame voting, Garciaparra fell off the ballot after two years, and his chances via the Era Committee are probably remote. But he’s a classic example of why peak value is underappreciated. He played six full seasons with the Red Sox and was above 6 WAR all six seasons, finishing eighth, second, seventh, ninth, 11th and seventh in the MVP voting. He won two batting titles, hitting .357 in 1999 and .372 in 2000 — the highest by a right-handed hitter since integration. He couldn’t stay healthy after the Red Sox traded him, batting 500 times just once. But for a half decade there, he was as popular as any player in Red Sox history, and I think his top-10 five-year peak makes him worthy of Hall consideration.

Hall of Famer: Hughie Jennings

Career WAR: 41.5 (38th)

Five-year peak: 35.4 (7th)

85.3% of career value in five best seasons

The star shortstop of the famed Baltimore Orioles teams of the National League in the 1890s, Jennings played 100 games in just seven seasons but was brilliant in five of them, and Baseball-Reference rates him as the NL’s best position player four straight seasons from 1895 to 1898. He would’ve been the Gold Glove shortstop of the era if that award had existed, and he hit .401 in 1896 (good for second in the league). One of his best skills, however, was getting hit by a pitch — 287 times, still most in MLB history. He later managed the Tigers for 16 seasons, including three straight AL pennants from 1907-09, and while he was elected to the Hall of Fame as a player in 1945, it’s possible his managing career helped get him over the top.

What might have been: You may know the Dickie Thon story. He came up with the Angels, was traded to the Astros, had a good season in 1982 (6.1 WAR) and then an even bigger breakout 1983 (7.4 WAR) at age 25, when he hit 20 home runs (a lot of home runs for a shortstop back then, let alone in the Astrodome) and made the All-Star team. Early in the 1984 season, Mike Torrez hit him in the left eye with a pitch. He made it back in 1985 and played nine more seasons, but his vision in that eye — or his offense — was never the same.

LEFT FIELD

Non-Hall of Famer: Albert Belle

Career WAR: 40.1 (37th among left fielders)

Five-year peak: 30.2 (19th)

75.3% of career value in five best seasons

Since he had four seasons with an OPS over 1.000, I thought Belle would fare higher on the peak-value list, but factor in: a) His two best seasons came in the shortened seasons of 1994 and 1995 (including 5.7 WAR in just 106 games in ’94 and a 50-homer, 52-double season in ’95 in 143 games); b) His defense was bad. Forced into early retirement due to an arthritic hip, Belle’s .564 slugging percentage ranks 12th among players with at least 6,000 plate appearances.

Hall of Famer: Jim Rice

Career WAR: 47.7 (27th)

Five-year peak: 30.5 (17th)

63.9% of career value in five best seasons

Rice is a soft Hall of Famer, making it essentially on his high peak, when he won one MVP Award in 1978 and had five other top-five finishes. As you can see from modern analysis, however, that peak still fails to crack the top 15 among left fielders. He batted 2,382 more times than Belle, yet their career power numbers are similar: 382 home runs and 1,451 RBIs for Rice, 381 and 1,239 for Belle. After a contentious Hall of Fame debate, Rice finally made it on his final year on the ballot. There will be no similar support for Belle, who has appeared on two Era Committee ballots, receiving fewer than five votes in both 2017 and 2019. With the steroids crowd and Curt Schilling eligible to join the Today’s Game ballot this December, Belle might not even get on a ballot again anytime soon.

What might have been: Lefty O’Doul came up to the majors as a pitcher in 1919, scuffled around, went back to the Pacific Coast League, became a full-time outfielder and finally made it back to the majors in 1928 when he was 31 years old. He would win two batting titles, hitting .398 with the Phillies in 1929 (7.4 WAR) and .368 for Brooklyn in 1932 (6.3 WAR). He was a regular for only four seasons, and no doubt if he had come up originally as a hitter, playing in that high-average era, he would have had a great shot at 3,000 hits and the Hall of Fame.

CENTER FIELD

Non-Hall of Famer: Dale Murphy

Career WAR: 46.5 (35th among center fielders)

Five-year peak: 33.1 (14th)

71.2% of career value in five best seasons

Two-time MVP Murphy has long had his hard-core Hall of Fame advocates, and he no doubt had some stellar seasons — with 7.7 WAR in 1987 and 7.1 in 1983, two other 6-WAR campaigns and two five-win seasons, plus he ranks 10th overall in the 1980s in WAR among position players. Despite his popularity (the Braves could be seen nightly on cable TV across the nation back then) and admirable character, he peaked at 23% on the BBWAA ballot. His five-year peak WAR is strong and the back-to-back MVP awards help, but it’s worth noting that his peak compares to some other non-Hall of Fame center fielders like Jimmy Wynn (33.2), Kenny Lofton (33.0) and Jim Edmonds (32.1), all of whom also ended up with more career WAR. Still, for a few years there, Murphy was “the man,” and given how he compares to Jim Kaat and Tony Oliva, two other well-liked players with marginal Hall of Fame credentials who were just elected via the Golden Days committee, I could see the tune changing for Murphy the next time he appears on the Modern Baseball committee ballot (December 2023).

Hall of Famer: Hack Wilson

Career WAR: 38.7 (48th)

Five-year peak: 30.7 (22nd)

79.3% of career value in five best seasons

Wilson is the ultimate peak Hall of Famer, hitting .333/.419/.612 with the Cubs from 1926 to 1930, with nearly 80% of his career value coming in those five seasons. He set the MLB record of 191 RBIs in the rabbit-ball year of 1930, when he also mashed 56 home runs, which stood as the NL record until Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa broke it in 1998. Both records helped Wilson gain Hall of Fame election in 1979 despite a short career. (The hard-drinking Wilson declined rapidly after 1930.) Wilson wasn’t exactly a one-year wonder, but would he be a Hall of Famer if he’d had 181 RBIs instead of 191? Unlikely, and we can see now that even his peak, by modern evaluation metrics, probably wasn’t dominant enough in itself to warrant selection.

What might have been: Pete Reiser is one of the most famous “what if” cases in MLB history. In his first full season in 1941 with Brooklyn, he led the NL in batting average, slugging, OPS, runs, doubles and triples at age 22. In July 1942, hitting .356 at the time, he chased after a long fly ball in St. Louis and crashed into the concrete wall. He had a fractured skull and separated shoulder, and despite the Cardinals’ team doctor recommending he not play again that season, he was back in the lineup a week later. He was never the same, World War II interrupted his career, and he suffered numerous other injuries when he came back.

RIGHT FIELD

Non-Hall of Famer: Dave Parker

Career WAR: 40.1 (45th among right fielders)

Five-year peak: 32.1 (16th)

80.0% of career value in five best seasons

Like Murphy, Parker has a loud cadre of supporters, who point to his status as “the best player in baseball” circa 1978, when he won NL MVP honors with the Pirates, as well as some respectable career numbers with 2,712 hits and 1,493 RBIs. Indeed, Parker did have an outstanding peak, with his top five seasons coming in 1977 (7.4), 1978 (7.0), 1979 (6.7), 1975 (6.3) … and 1985 (4.7). What happened between 1979 and 1985? Well, Parker gained weight, he had injuries, he had a cocaine problem, and all three affected his production.

Parker cleaned himself up and bounced back with the Reds in his mid-30s and then became the spiritual leader of the Bash Brothers A’s. He finished second in the MVP voting in 1985 (he led the NL with 125 RBIs) and then fifth in 1986, a season in which Baseball-Reference pegs his value at just 0.3 WAR. What? Parker drove in 116 runs that year, 97 in 1987, 97 again in 1989, 92 in 1990, then 39 years old and DHing for the Brewers. That’s 402 RBIs over those four seasons, but with a total value of 0.5 WAR. Parker had mediocre OBPs and no defensive value by then, so his Hall of Fame case has been a battle of old-school stats, reputation and peak value versus modern analytics. I wouldn’t rule out the possibility of Parker getting in, as he might be getting closer: In the 2018 Modern Baseball Era Committee voting, he received fewer than seven votes (specific totals aren’t released), but on the ballot again in 2020, he had climbed to seven.

Hall of Famer: Chuck Klein

Career WAR: 46.6 (30th)

Five-year peak: 32.0 (17th)

68.7% of career value in five best seasons

Klein put up some monster stats with the Phillies from 1929 to 1934, hitting .359/.414/.637 while averaging 36 home runs and 139 RBIs, including an MVP Award in 1932 and a Triple Crown in 1933. Klein’s numbers need to be understood in context. That was a high-scoring era and the Phillies played in the Baker Bowl, where the right-field wall was 280 feet from home plate and right-center just 300 (which helped Klein rack up big assist totals as well). He hit .424 with 122 home runs at home those five seasons and .294 with 58 home runs on the road. Klein topped out at 27% on the BBWAA ballot, but the Veterans Committee elected him in 1980 after a letter-writing campaign by his sister-in-law and a Philadelphia schoolteacher got him reconsidered in 1979.

What might have been: Johnny Callison was another Phillies right fielder, an excellent player from 1962 to 1965, averaging 6.5 WAR, with a high of 8.1 in 1963. He had a powerful throwing arm — he had 90 assists over that span, leading all outfielders each season (he had 26 in 1963, a total since equaled only by Parker in 1977). Callison would have won the 1964 MVP Award if the Phillies hadn’t famously blown a big lead in their final 10 games (he finished second). Then, in 1966, still just 27, his power just kind of evaporated. Callison would blame leg injuries. He tried wearing glasses. He was a guy who worried a lot and lost confidence. It happens.

PITCHER

Non-Hall of Famer: Johan Santana

Career WAR: 51.1 (66th among starting pitchers since 1920)

Five-year peak: 35.6 (29th since 1920)

69.7% of career value in five best seasons

Finally, we get to the impetus of this little exercise: Sandy Koufax. I picked Santana as Koufax’s comp for a few reasons: 1. Both are left-handed; 2. They ended up with similar career totals in WAR (slight edge to Koufax) and innings (Koufax had 299 more, meaning Santana averaged 5.0 WAR per every 200 innings to 4.6 for Koufax); 3. Their five-season peaks came across five consecutive seasons. Those numbers:

Santana, 2004-08: 86-39, 2.82 ERA, 1,146.2 IP, 1,189 SO, 157 ERA+

Koufax, 1962-66: 111-34, 1.95 ERA, 1,377 IP, 1,444 SO, 167 ERA+

Koufax won three Cy Young Awards (when there was just one winner across both leagues). Santana won two but should have won three (he was clearly the best pitcher in 2005 over Bartolo Colon). Obviously, 86-39 is not 111-34, although their adjusted ERAs — Koufax pitched in a low-offense era in a pitcher-friendly home stadium — bring the ERA gap a lot closer. Still, Santana wasn’t quite Koufax, but it’s reasonably close, and Santana did a little more outside of his peak than Koufax did. Koufax made the Hall of Fame on the first ballot while Santana received just 10 votes out of 422 voters, his outstanding peak as the best pitcher in baseball summarily dismissed. He deserved more consideration.

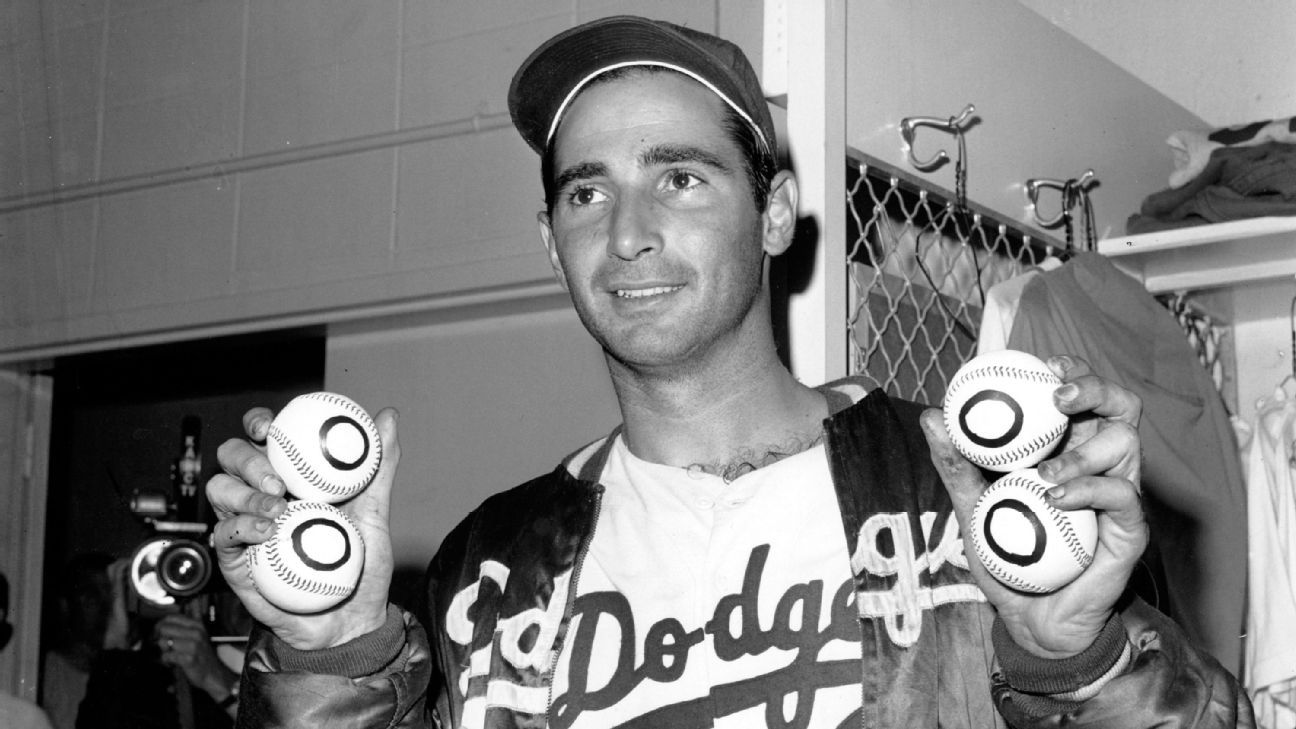

Hall of Famer: Sandy Koufax

Career WAR: 53.1 (57th since 1920)

Five-year peak: 42.1 (10th since 1920)

79.3% of career value in five best seasons

I counted peak value only since 1920, bypassing dead-ball-era and 19th-century pitchers who pitched ungodly numbers of innings. So who rates ahead of Koufax? The top 10:

Lefty Grove, 51.3

Roger Clemens, 49.2

Randy Johnson, 46.9

Pedro Martinez, 45.8

Bob Gibson, 43.9

Tom Seaver, 42.6

Robin Roberts, 42.6

Greg Maddux, 42.3

Bob Feller, 42.3

Koufax, 42.1

Of note, Koufax’s rival Juan Marichal is close behind at 41.3 WAR, and while Koufax had seasons where he went 27-9, 26-8 and 25-5, Marichal went 26-9, 25-6 and 25-8. Marichal, however, came in at No. 74 on our list, while Koufax was No. 32. Why does Koufax’s legacy still loom so large?

–The World Series. He beat the Yankees twice in the 1963 World Series, including a then-record 15-strikeout game (Gibson later topped him with 17), and then shut out the Twins in Game 5 and Game 7 (on two days of rest) in 1965.

–The no-hitters. Koufax’s four no-hitters were the most until Nolan Ryan’s.

–Koufax was a power pitcher, Marichal more of a finesse hurler. Koufax’s 382 strikeouts in 1965 set a modern record (since broken by Ryan with 383).

–Koufax retired as king of the mountain, forever at the top of his game.

What might have been: Frank Tanana won 240 games, but there is still a “what if” question to his career. As a young fireballer with the Angels from 1975 to 1977, he went 50-28 with a 2.53 ERA (23.1 WAR). Teammate Nolan Ryan went 50-46 with a 3.16 ERA (13.9 WAR). Tanana hurt his arm and hung on forever as a junkballing lefty, but, oh, what might have been.