“POP WANTS TO talk to you.”

The server is speaking to a man named Jeremy Threat — and from the tone in his voice, something is clearly amiss. Threat hustles back to the main dining room of Spataro Restaurant & Bar, an Italian restaurant in Sacramento, California, that has been overrun by the San Antonio Spurs. Players, coaches, management, ownership. All are seated along a handful of long, rectangular tables. The room is pin-drop silent. Some 40 pairs of eyes are trained on Threat, the venue’s 29-year-old general manager and wine director.

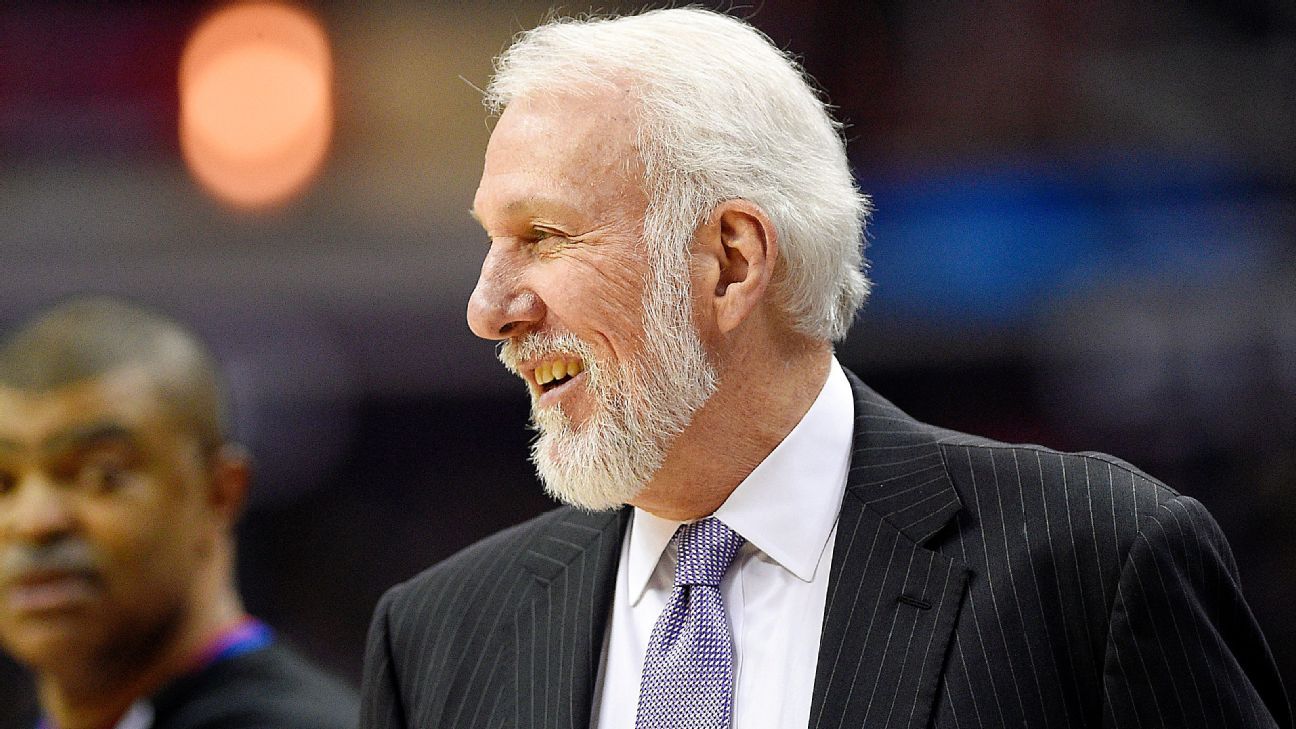

Seated at the head of one of those tables, beside a window that offers a sweeping view of the California state capitol building across the street, is Spurs coach Gregg Popovich.

“Explain this,” Popovich barks to Threat, brandishing the wine list. Threat is perplexed.

“How did you do this?” Popovich asks. “This list has some of my favorite wines. Did you guys just have this? You’ve got to explain yourself.”

Threat explains himself. He explains how hours earlier, when he had learned that the Spurs might be coming in, he’d recalled a Wine Spectator magazine feature that had listed many of Pop’s favorite wines. He explains how he’d called a nearby friend who possesses a deep cellar, how his friend had hauled in about 120 bottles worth roughly $50,000 in total, how Threat had built the list that Pop now holds of 54 wines: the legendary 1990 Chateau d’Yquem; the acclaimed Masseto in 1996, 1997, 1999 and 2001 vintages; the iconic 1994 and 1995 Ornellaia.

Popovich is incredulous. “You’ve got to be kidding me. Really?” Then he orders 10 bottles. And when they arrive, the coach transforms into a happy sommelier, bounding about the room, pouring for everyone. “You’ve got to try this!” At the end of the night, he buys another 10 bottles — to go.

By the next morning, Threat’s life has changed forever. He just doesn’t know it yet. All he knows is that the corporate office of the restaurant group is on the line. “I think there’s an error in your computer,” one of the owners tells Threat. “It shows you sold about $15,000 to $20,000 worth of wine at the end of the night, and you’re not even open then. What happened?”

A few days later, Threat’s star begins to rise. Word spreads. He’s interviewed by the local paper. Guests begin pouring in, asking for Popovich’s list. And within a couple years, Threat will go on to work with the acclaimed Thomas Keller Restaurant Group. There, he’ll engage with some of the biggest wine connoisseurs on the planet. But he will never forget the impact of Popovich: “He was as knowledgeable, if not more knowledgeable, than the majority of them.”

IN SUMMER 2013, before an NBA Finals loss to LeBron James and the Miami Heat, Gregg Popovich is asked about his coaching legacy. “What’s my legacy?” he quips. “Food and wine. This is just a job.”

He’s kidding — but he’s not. As much as Popovich knows about hoops, he really knows food and wine. “I don’t know that he doesn’t know more about wine than he does about basketball,” former Spurs assistant coach P.J. Carlesimo says. Popovich scouts restaurants and wine lists as obsessively as he might any opponent. Before games, in his office, he can be found watching the Food Network. Sommeliers and restaurateurs claim to owe their careers to the man.

As absurd as it seems, one of the greatest basketball coaches in history might be more revered in the culinary world.

There’s a restaurant in San Francisco that Cavaliers forward Kevin Love frequents, and when he visits, “Everybody in there is always like, ‘Popovich, Popovich, Popovich,'” Love says.

When former NBA coach Larry Brown visits Sistina or Scalinatella — restaurants in New York — staffers there ask him, “Oh, have you seen Coach?” And he knows exactly who they mean.

“You can’t say enough about the man,” says Rick Minderman, store director of Corti Brothers, a gourmet grocery store and wine shop in Sacramento, where customers directed to the store by Popovich will often come in and say, “What does Coach buy?”

“I’ve never forgotten him,” says Virginia Philip, a master sommelier who served Popovich in the 1990s at Ruth’s Chris Steak House in San Antonio.

Chris Miller, a master sommelier who’s served Popovich in several cities, says, “I can’t possibly express the respect that I have for that man.”

In Phoenix, James Beard award-winning pizza-maker Chris Bianco, who has also served the coach, says: “I’m a huge Gregg Popovich fan.”

Chef Wolfgang Puck says simply: “[Popovich] knows wine.”

Over the past few decades, Popovich has sliced a culinary trail across America — one curated in private, if not in secret. He’s patronized the finest restaurants, spent millions of dollars, left countless five-figure tips, turned himself into a first-order oenophile. He’s forged fast friendships with the nation’s premier gourmands. And all to a singular purpose. As one source close to Popovich says, “It’s a passion for him, but it’s also a tool.”

In the NBA, the Gregg Popovich meal is the dining room where it happens — a roving retreat through which the Spurs have forged a team culture that’s the envy of the league. But for those in the league who’ve not secured the invite, Pop’s legendary dinners remain shrouded in mystery and no small amount of fascination.

And so it was that over the past 18 months we talked to dozens of NBA and college coaches, current and former NBA players, team executives, chefs and sommeliers, all to answer a question: Why does Popovich — the NBA’s all-time winningest coach and architect of a two-decades-long basketball dynasty — care so damn much about dinner?

BORIS DIAW STRIDES the sideline after a Spurs practice, armed with a burning question. He approaches Steven Koblik, a friend of Popovich’s since his days coaching Division III Pomona-Pitzer College, where Koblik was the team’s academic adviser.

“Has Coach always been like this?” Diaw asks.

“Boris,” Koblik replies, “he came out of the womb like that.”

The “this” that Diaw is referencing, and the “that” Koblik is confirming, are what could generously be called Popovich’s “legendary intensity” and less generously his “legendary withering disdain.” You’ve seen it unleashed in team huddles, seen sideline commentators cower before its wrath. But for as long as Koblik has known Popovich, he’s known this: Popovich could not be such a famous curmudgeon unless there were another side of him. A side expressed, quite often, through food.

“It is a subtle way of saying, This is also what I’m like,” says Hank Egan, Popovich’s basketball coach at the Air Force Academy.

How Popovich became like that traces back nearly five decades, to Napa, California, circa 1970, a mythical moment in American wine — before President Richard Nixon took a Napa sparkling wine to his 1972 “Toast to Peace” with China’s premier; before the 1976 Judgment of Paris competition, where, for the first time, California wines bested some of the top French wines.

Back then, Napa was a sleepy tourist destination filled with aspiring winemakers. And it was there that Popovich caught the wine bug, with help from Michael Thiessen. Thiessen, a year older than Popovich, had played basketball with Pop at the Air Force Academy and, afterward, migrated to Stanford Law School. A year later, Popovich would also head to California, to be stationed near Sunnyvale, California, two hours south of Napa.

The two weren’t all that close at the academy, but that changed in California. Popovich moved into Thiessen’s apartment, which Michael shared with his wife, Nancy. And in their spare time, in search of cheap fun, they’d visit wineries that would, in a few years, become world-famous: Stony Hill, Mayacamas, Ridge. They’d sip wines now considered some of the finest California has produced; back then, the bottles cost only a few bucks. They spent time at Corti Brothers, which is considered a birthplace of the gourmet food revolution.

“It was a magical time,” Thiessen says.

A few years later, in 1979, the budget was lean when Popovich landed at Pomona-Pitzer, his first head-coaching job. But his players soon found there’d always be an ample team meal awaiting them in the dining hall on game day. And when they’d travel to food destinations like New Orleans or the Bay Area, they’d have at least one memorable meal together as a team. “It was important to him that, obviously, we were fed, but also that we had the opportunity to eat together,” says Tim Dignan, who played at Pomona under Popovich.

They’d all go to Pop’s apartment — in an on-campus dorm — to eat and watch game tape on VHS. On Thanksgiving and Christmas, Popovich and his wife, Erin, would cook meals for the players who’d stayed on campus. “They made us feel like family,” says Aaron Whitham, another of Popovich’s former Pomona players.

Popovich became “obsessed,” says Dan Dargan, another ex-Pomona player, with the 1980s television soap opera “Falcon Crest,” which depicted warring factions of families in the wine industry, set in a fictitious wine region based on Napa Valley. In Popovich’s dorm, he kept a wine rack. At end-of-season banquet dinners, he presented bottles to staffers, explaining why that wine and its characteristics matched that staffer.

Today, those close to him say Popovich’s office at the Spurs’ practice facility looks not unlike a wine cellar: bottles often all over the place, cases stacked up in the hallway. And in Popovich’s home, Thiessen says, resides the very first bottle the two purchased together.

IT’S THE FIRST round of the 2010 playoffs, and the Spurs are getting trounced by the Mavericks in Game 5 in Dallas. Typically, during the postseason, Spurs coaches convene in Popovich’s hotel suite after games — over a meal, of course — to break down film. But during this blowout, Popovich turns to a Spurs official and tells him to call The Capital Grille; the whole team is coming in.

“Hey, we’re together,” Popovich tells his troops after the 103-81 loss. “Let’s eat. That’s basketball. … We’ll get back to work tomorrow.”

The Spurs close out the series in the next game.

Before Game 6 of the 2013 Finals, Popovich prepares a title-clinching celebration at a favorite Miami restaurant, Il Gabbiano. But then Heat guard Ray Allen buries a miracle corner 3-pointer to send the game to overtime — and the Spurs lose. “I had never seen our team so broken,” Spurs guard Tony Parker says later.

“Pop’s response was, ‘Family!'” Brett Brown, then a Spurs assistant, later tells ESPN. “‘Everybody to the restaurant. Straight there.'”

Popovich is already on his way, making a mad dash in a private car to the waterfront eatery. Tables are rearranged — the team will sit in the center, coaches nearby, a ring of family around them. Popovich orders food. He orders the wine. He sits at the head of a table, takes a sip of wine and gathers himself. As the team bus arrives, he greets every Spur who passes through the door.

Over the next few hours, Popovich works the dining room — talking to players, rubbing their shoulders. “In terms of just trying to just hook everybody up to life support and resuscitate everybody, it was the most amazing display of leadership,” former Spurs assistant coach Chad Forcier says. And though the Spurs didn’t win that series, losing to the Heat in Game 7, they would destroy Miami the following June, in five games.

Some investments, like wines, take time to mature.

“Dinners help us have a better understanding of each individual person, which brings us closer to each other — and, on the court, understand each other better,” former Spurs guard Danny Green says. On the road, whenever possible, the Spurs tend to stay over and fly out the next morning. “So we can have that time together,” former San Antonio center Pau Gasol says. “I haven’t been a part of that anywhere else. And players know the importance of it as well — and how important it is to Pop.”

Says one former player: “I was friends with every single teammate I ever had in my [time] with the Spurs. That might sound far-fetched, but it’s true. And those team meals were one of the biggest reasons why. To take the time to slow down and truly dine with someone in this day and age — I’m talking a two- or three-hour dinner — you naturally connect on a different level than just on the court or in the locker room. It seems like a pretty obvious way to build team chemistry, but the tricky part is getting everyone to buy in and actually want to go. You combine amazing restaurants with an interesting group of teammates from a bunch of different countries and the result is some of the best memories I have from my career.”

THE CALL COMES in the afternoon: Pop needs the private dining room tonight. “Anything for Pop” is the mandate at Cured, a restaurant in San Antonio’s Pearl District. Such a call isn’t rare, but even after all of Popovich’s visits, Cured’s owner and chef, Steve McHugh, says it’s still sweat-inducing: “You know how you don’t want to let your parents down? He’s someone you don’t want to let down.”

On this day, in spring 2015, Popovich is entertaining a group of Spanish basketball officials. An hour before dinner begins, he arrives at the restaurant, a gastropub in a rustic, century-old building, toting Spanish wines from his cellar. Popovich heads to the end of the eight-seat bar and asks the general manager for the wine list, seeking reinforcements.

After much deliberation, he selects a white to pair with the charcuterie and appetizers, then asks that the reds be opened so they’re ready for the main dishes. Standing behind the bar, McHugh, who emerges from the kitchen to greet the coach, marvels at how Popovich orchestrates every element.

“Why all the effort?” McHugh askes.

“You know, the NBA makes us do these kind of tours,” Popovich replies, belly-up to the bar. “Your typical NBA team hands this task off to some assistant coach or to some front-office guy, ‘Hey, take this group around, do a photo with the coach.'”

Popovich, though, believes in hosting these affairs personally.

Then he tells McHugh a story about how many years ago, he had a group in from Argentina and, “I blew ’em away, and we wined ’em, we dined ’em. We gave them photo ops. We gave ’em everything they wanted.” And how years later, when a kid named Manu Ginobili came onto the scene, “that’s how we found out about Manu, when nobody else knew about him.”

THERE ARE INGREDIENTS, if you will, for Pop’s dinner recipe — from how many sit at his table, to what bottles will be present, to what time he’ll arrive. Popovich, who declined to comment for this article, triangulates his research, examining the wine list and menu before a reservation is made weeks, if not months, in advance. The ambiance, lighting, music — all are elements to be factored in. And when it comes to the choice of restaurant, in the NBA, his word carries as much weight as Michelin stars.

“If Pop recommends a restaurant, you go to it,” ex-Cavaliers general manager David Griffin says.

Take Seven Hills, a hole-in-the-wall Italian restaurant in San Francisco’s Nob Hill. It has 16 tables and seats 40 guests. When the Cavaliers were in the 2015 Finals against the Warriors, a group of front-office staffers wanted a place to dine. One Cavs assistant had spent three seasons as a video coordinator with the Spurs and recommended Seven Hills, saying Popovich had taken the team there and loved it. Done. The staff went, and loved it. A second group went later that week.

Then word got out. “We told so many people about it at the Finals, it was slammed with NBA folks throughout,” Griffin says. That, of course, was the first of four consecutive Finals between the Cavs and Warriors. Now, Griffin says, “You can’t get [a table there] during an NBA event.”

“Dinners help us have a better understanding of each individual person, which brings us closer to each other — and, on the court, understand each other better.”

former Spurs (and current Raptors) guard Danny Green

But the work is not done yet. Once an establishment is chosen, decisions about wine are made. Popovich prefers buying whites from the restaurant and likes them chilled. As for reds, he’ll pull bottles from his cellar and assign them, individually, to his assistants.

“Bring this one to dinner tonight,” he’ll say, handing a bottle to a staffer.

“This one’s for dinner in New York,” he’ll say to another.

“This one’s for D.C.,” he’ll say to another.

“Bring this one to Philly,” he’ll say to another.

The responsibility is on each staffer to care for that bottle as if it were their own child. Don’t lose it, don’t break it, don’t store it improperly.

At some point each night, instructions are shared about dinner — the time and place. But it’s all but impossible to arrive before Popovich, who shows up well in advance to make sure everything’s in order. As staffers arrive, Pop will be at the head of the table, arms out, palms in the air, a smile on his face, the Godfather himself.

There are typically five other chairs at Popovich’s table — a point of emphasis, former Spur Steve Kerr says. Six guests at a table, Pop believes, fosters diversity of conversation without folks breaking off into separate chats. Not too many, not too few — just right.

For members of his staff, invites are a given. For others, invites are coveted — perhaps the most coveted dinner invites in the NBA. “When I get invited, I don’t pass up the opportunity,” former Spurs small forward Sean Elliott says. Says former Spurs executive and former Pelicans GM Dell Demps: “You know, people would pay for this.”

The value of the golden ticket is, in many ways, incalculable: Nuggets coach Mike Malone says he owes his entire NBA head-coaching career to a 2005 Basketball Without Borders trip, when he says he spent a “week-and-a-half in Argentina drinking wine with [Popovich].” Afterward, Popovich made a call on Malone’s behalf, helping him earn an NBA coaching gig.

Invaluable? Yes, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t a price to be paid: As one source close to Popovich says: “Sometimes, you just want to get a Shake Shack burger and go to the room. But there’s peer pressure. It truly is his passion. It’s not everyone’s passion.”

Then there’s what’s known in Spurs circles as the “double meal.” These evenings, some say, can be a bit much, two full, back-to-back, sit-down feasts. Dennis Lindsey, a former Spurs executive and the current Jazz GM, recalls one such evening when he and another staffer, full from the first meal, plotted to subtly skip a few courses during the second. “Don’t think I didn’t notice that you guys were skipping courses,” Popovich told them later in the evening.

Says Lindsey: “I think I made one double meal. It was all I could handle.”

ONE NIGHT SEVEN years ago, at Michael Mina’s flagship San Francisco restaurant, which bears his name, the Michelin star-winning chef, who oversees an empire of restaurants, watches Popovich talk to his team. Mina has long admired Popovich from afar, admired how consistent his Spurs were, night after night, year after year. He wonders what Popovich’s secret is.

“I honestly thought he was just this really hard-nosed, bust-your-ass coach, and that’s how he got them to do it,” Mina says. But now, watching Popovich with his players in the dining room, Mina realizes “how gentle he was, and how it was about educating in a much different way.”

Later, when Mina grills Popovich about team-building, Popovich says the key is to take people out of their element, have them experience new things, and learn from it together. Consider one meal in fall 2016, part of the Spurs’ annual preseason coaches retreat — held, naturally, in Napa Valley. During retreats, it’s long days watching game film in conference rooms. At night, they feast. And on this night in mid-September, with training camp days away, they head to nearby Yountville, to one of the most prestigious restaurants in the world.

Meals at The French Laundry routinely run well north of $300 per person. Reservations are often required months in advance. It’s a three-Michelin-star destination, the highest honor, one bestowed upon only 15 restaurants in the country. The late Anthony Bourdain once called The French Laundry “the best restaurant in the world, period.” It’s also a personal favorite for Popovich. The legendary chef there, Thomas Keller, has become a close friend of his. And on this night, in the 62-seat haven, Popovich and his colleagues are tended to by a staff that moves with synchronicity, delivering 12 courses of French-inspired American fare from the chef’s tasting menu. Throughout the meal, Popovich — who often frequents chef’s tables, the private nooks from where diners can view the kitchen floor — is effusive, talking to his charges about everything happening around them, expressing awe for the precision and teamwork required to run a restaurant of this caliber.

Says Michael Minnillo, general manager of The French Laundry: “He’s always teaching.”

BY NOW, YOU’RE perhaps wondering something along the lines of: Who the hell pays for all this? How much does it cost? And how can I jump on this gravy train?

If so, know this: At the end of the night, Popovich picks up the tab — always — including for former Spurs who happen to be in the same restaurant, even if they’re not in his group. It’s a generous bylaw, and it has more than once created a cat-and-mouse game where former Spurs try to glean — through the hotel concierge or friends in Pop’s circle — where he’s dining that night. Then, like clockwork, they just so happen to arrive at the same restaurant for a free meal. (Two primary culprits in this scam, sources say, are Kerr and Danny Ferry. Popovich has been known to sometimes try to trick offenders by alluding to certain places, but they often find out anyway, much to his delight.)

Then comes the tip, and for this, Popovich is renowned. In 2017, he reportedly left a $5,000 tip on a bill of $815.73 at a restaurant in Memphis, Tennessee, but one restaurant owner who’s served Popovich many times reports that he’ll often tip $10,000 on a “nothing meal,” order bottles of wine for the kitchen staff and, upon leaving the restaurant, pull out a thick wad of cash and ask that it be delivered directly to said staff.

“I haven’t been a part of that anywhere else. And players know the importance of it as well — and how it important it is to Pop.”

former Spurs (and current Bucks) center Pau Gasol

An official at one well-known Italian restaurant in Manhattan — host to numerous big-name celebrities — reports that some of its most successful nights are when Popovich comes through the door. And though NBA players on the road might give game tickets to family or friends, Popovich often gifts his to a waiter or sommelier from a restaurant he visited the night before. He’ll write handwritten notes to restaurant staffers, as he did after a dinner at three-Michelin-star Saison in San Francisco. Then, for good measure, he’ll mail to them some of his wine — yes, his wine, from his own private label.

Says Larry Brown of Popovich, who hails from the industrial town of Merrillville, Indiana: “He didn’t have diddly squat, and I think he knows how blessed he is.”

How much, in all, does Popovich spend annually on food and wine? That’s hard to say. But he reportedly earns $11 million a year, the highest salary in the league for a head coach. Considering the offerings from his private wine label and that he holds thousands of bottles in his cellar, plots out dozens of high-end dinners per year at some of the country’s most high-end restaurants, drops $20,000 on wine alone at some dinners, and routinely leaves exorbitant tips — well, it’s not a stretch to suggest that Popovich might ultimately drop a seven-figure annual investment on food and wine. “He’s spent more on wine and dinners than my whole [NBA] salary,” former NBA coach Don Nelson says. But in San Antonio — where Popovich has won more with his team than any NBA coach has with a single team in history — the investment, apparently, has been worth it.

IT’S A DECADE ago, and Spurs assistant coach Chip Engelland walks into the video staff’s editing room and announces they have a new task. “Hey guys,” Engelland says, “this is important.”

At a Spurs team dinner prior to that, several dishes in and many bottles deep, someone at the table had spoken up: “We should do something to remember these dinners by.” And with that, a nightmare duty was born.

They had begun by collecting menus, photos of those present, and most of the bottles. Now their mission is to compile mementos from the dinners and arrange them chronologically. To do that, they first have to remove the labels from the bottles without damaging the labels themselves — and have you ever tried removing a label from a wine bottle? Now imagine doing it for a bottle that might cost thousands of dollars. And now imagine doing that while knowing that it’s for Popovich, a man of precise detail who treasures these dinners as much as, if not more than, the game itself.

“It’s a stressful situation,” former Spurs video coordinator Mo Dakhil says. Painstaking, slow, careful. It takes time, in between, you know, their actual day jobs and scouting assignments.

Sometimes, after a long road trip, a dozen empty bottles arrive — and that might take two hours, maybe three, for a staff of four.

They must also keep track of which bottle goes with which dinner, what was on that menu and on what date it took place. Then, incrementally, every keepsake is delivered to a professional scrapbooker, who assembles the material into a leather-bound book, several inches thick, with thick, parchment-paper pages, expensive (in the four-figure range, a source says), but, according to the franchise, worth every penny.

And every Jan. 28, on Gregg Popovich’s birthday, another year of conspicuous consumption goes in the books.

“LOOK, POPOVICH IS coming in tonight. And he’s really into wine — like, really into wine. This is your only focus tonight.”

Jienna Basaldu looks at her boss and nods. She’s grown up watching the NBA, especially her hometown Kings, and, of course, knows about Popovich, but what she mostly knows — aside from the notion that he’s good at his job — is the steely stare that’s chilled the spine of many a sideline reporter. And now she, a 29-year-old sommelier who passed the exam to earn that title a few months prior, will be taking care of him.

She’s nervous to begin with. And that’s before Popovich strolls into Ella Dining Room and Bar with five staffers, like a scene from “Reservoir Dogs.” But immediately, he’s kind, courteous. He explains that they’d like to do side-by-side comparisons of Old World wines vs. New World wines: a white Burgundy from France versus a chardonnay from California, a French red Burgundy against a California pinot noir.

Basaldu loves the idea. It’s a wine geek’s delight. Throughout, Popovich turns to Basaldu, asking her to explain elements of each — the region, producer, vineyard, why it’s best served in this type of wine glass. “Oh, repeat that,” he says, gesturing toward his staff. “Tell everyone at the table.” Basaldu feels empowered. So much of what he orders happen to be wines that she’s studied for her recent exam. She catches a rhythm, like a shooter who can’t miss. And toward the meal’s end, Popovich says, “Oh, save all the bottles. Give them all to my assistant. They’re going to scrapbook them. We need to make sure we have everything.”

As Popovich prepares to leave, Basaldu stands near the door. He stops and turns to her. “You’re too good for this place,” he says. “You’re going to do big things.”

Pop isn’t knocking Sacramento, or the restaurant where she’s worked for 2 ½ years, a place he’s visited many times. He’s referencing her promise.

“You’re so young, and you’re so well-spoken, and you’re so knowledgeable. It’s clear that you love this. When you love something like this, you hold onto it. You hear me?” “Yes, sir, Mr. Popovich,” she tells him.

Deep down, she’s always dreamed of going to San Francisco, among the biggest stages in her industry, but the leap from Sacramento has felt huge. She figures she might just stay in Sacramento forever. But his words resonate: “I will see you again. It will be somewhere else.”

Being a young woman in a male-dominated industry is daunting. Still, she tells herself, “Gregg Popovich sees something in me.”

Four years later, when Basaldu makes the leap and lands at The Morris, an acclaimed eatery in San Francisco’s Potrero Flats neighborhood, she looks back on that night with Popovich. And her voice will crack, recalling the time when this famous coach, known for his gruff exterior, gave her the push she needed — how he walked into her restaurant, recognized her game and helped change the course of her life.