What James Harden has done to the Utah Jazz through two blowouts goes back to his greatest humiliation — Harden’s meltdown, and Houston’s collective disintegration, against the San Antonio Spurs in the 2017 conference semifinals.

Harden eviscerated the Spurs in Game 1 of that series — a 27-point Rockets win that seemed to announce Houston as the primary threat to Golden State’s Western Conference hegemony. San Antonio won four of the next five games — the last three without Tony Parker, and the clincher without Kawhi Leonard.

The Spurs won that game in Houston by 39 points. Harden finished with 10 points on 2-of-11 shooting and six turnovers before fouling out. For months, he could not discuss the game with his closest confidantes. They would not dare broach the subject.

“It was like when you were a kid and you saw your parents fighting, no one would ever want to bring it up,” says Daryl Morey, Houston’s general manager. “No one could process it.” Gregg Popovich, San Antonio’s coach and president, approached Morey after the game to congratulate him on Houston’s season and express astonishment about what had just unfolded. “I don’t know what happened,” Morey recalls Popovich telling him. “That was strange.”

Houston’s brain trust attributed the collapse to fatigue from Harden’s pursuit of the MVP, abetted by Mike D’Antoni’s famously short rotations.

Harden was surely tired. He tweaked his diet and fitness regimen after that series. But the Spurs also unveiled a template for defending Harden that would spread across the league. It was simple: When Clint Capela set a pick for Harden, Capela’s man was to plant himself near the hoop and lie in wait for Harden.

They would not switch. They would not trap, exposing an easy slip pass to Capela. They would meet Harden at the restricted area and wager they could at least disrupt layups and lob passes. They would foist indecision onto him. They knew Harden would not accept the shots they were giving him; floaters and long 2s were verboten in Houston. It worked.

It was the lowest point in Harden’s career. He transformed it into a turning point — the catalyst for a reinvention that happened so gradually, piece-by-piece, you almost didn’t notice Harden becoming a completely different player.

After that Spurs series, Harden went about adding a floater. If top defenses were going to concede that shot, Harden would have to take it.

This season, he mastered it. Harden has attempted more than twice as many floaters as he did a season ago, and he has hit almost half of them, per Cleaning The Glass — an elite number.

The next step was more radical: eliminate the need for a screen altogether. “We used to talk about the screen as an escort for a double-team,” Morey says. “Why even give the defense the option?”

Harden was already a very good isolation player, but he would have to stretch the math beyond what anyone had dreamed possible to render the pick-and-roll — basketball’s staple play almost since the peach basket — obsolete. Enter the step-back 3 — an isolation worth three points if it goes in, which it has about 40 percent of the time this season.

Harden has drained 240 step-back triples in 2018-19. Stephen Curry led the league in total 3s with between 261 and 286 for three straight seasons from 2012-13 through 2014-15. Just making that many 3-pointers was revolutionary four seasons ago. Making that many step-backs was not a thing that existed in the NBA’s brainspace.

The threat of the step-back forced defenders into pressing Harden 30 feet from the rim. That made them easy pickings for a blow-by.

Harden had warped math, and opened new possibilities for Houston. Instead of having Capela screen around the 3-point arc, the Rockets can now station him at the dunker spot — along the baseline, at the edge of the paint — at the start of possessions. That doesn’t sound important, but in talking to opposing players and coaches, it has changed everything.

The pick-and-roll lob dunk is a dance of intricate timing. The ball handler must wait for his target to rumble into position. That delay gives the defense a chance to catch up. Any hiccup in cadence — any miscommunication — and the window for the lob closes.

Plopping Capela in the dunker spot dispenses with those fraught 30 feet of prelude. He is there already, feet planted, primed to cram.

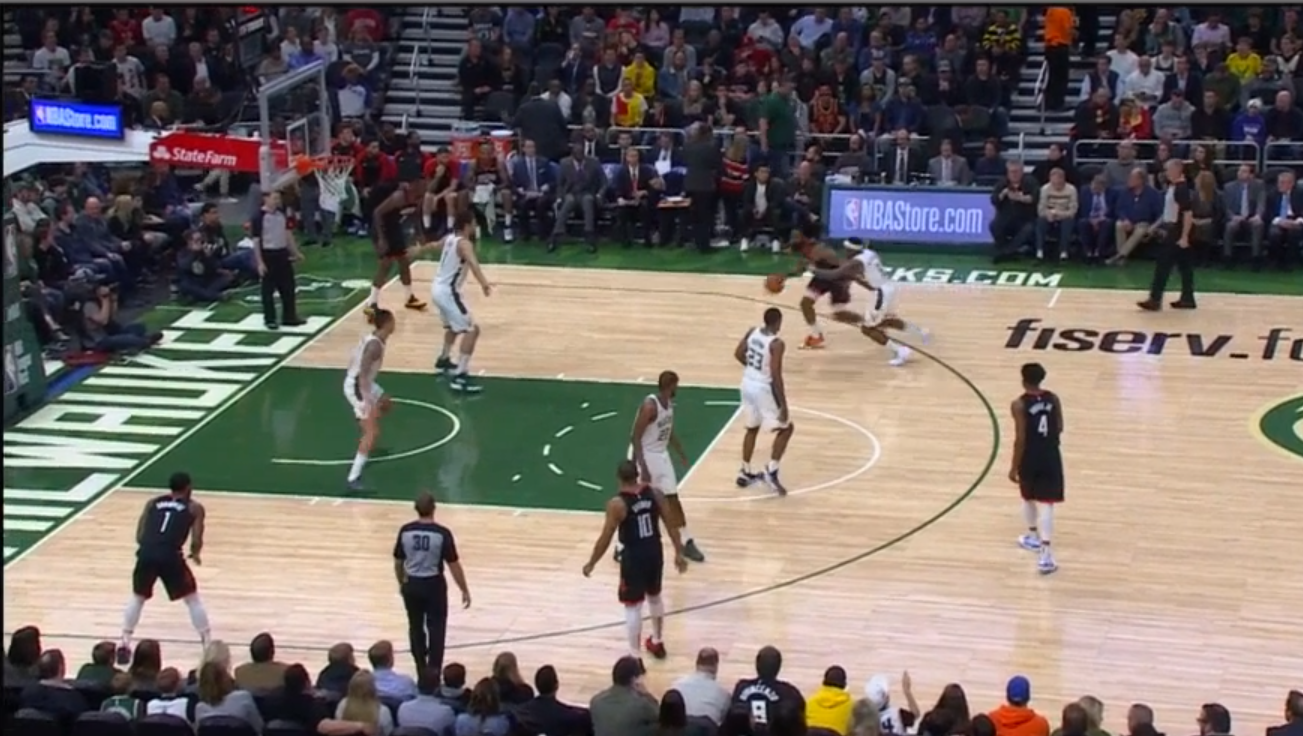

Opponents have grappled with this strange new geometry. The Bucks, as our Tim MacMahon detailed, fared best with an exaggerated variant of the Spurs’ method several teams — including Utah in this series — have imitated: climb atop Harden’s left shoulder to take away the step-back and force him right, slot Capela’s man in front of the rim, and hope to coax Harden into floaters — or deflect any lob pass.

Note all three Houston shooters set up to Harden’s left. In one sense, that makes life hard for Brook Lopez; if he steps away from Capela to barricade the rim, there is no teammate behind him to take Capela.

But the Bucks probably didn’t mind this alignment. Driving with his right hand and then passing across to the left side is one of the trickiest passes for Harden — as it would be for lots of lefties. It requires a less natural throwing motion — almost a backhand. Harden doesn’t get as much pace on those passes, or throw them with his usual accuracy:

It is the one pass Harden is a little reluctant to make. He will see it, and opt for something else. Look how open Chris Paul is on the left side on this possession from Houston’s Game 2 win:

There is zero chance Harden doesn’t see Paul. He tries a floater instead, and even with the massive improvement he has made, that shot is still the best-case scenario for any team defending Harden in this (and probably any) style.

Houston has its players aligned on this possession in a way that almost guarantees that pass to Paul will be the only easy one available. Capela is in the left dunker spot; Paul is the only shooter on that side. It is the responsibility of Paul’s defender — Ricky Rubio — to block Harden’s pass to Capela as Derrick Favors steps into Harden’s path. The defenders on the right side of the floor can stay home.

Favors does a nice job sticking close to the rim, and staying down until the last possible second. He reveals nothing. He forces the decision onto Harden.

The Jazz are betting Harden won’t make that pass, or that he will throw it softly enough for the defense to recover.

Houston can unlock a more comfortable left-to-right laser for Harden by sliding Capela across the paint to the right dunker spot:

Rudy Gobert shifts away from Capela to snuff Harden, and the closest help defender to crack down on Capela is naturally on that right side. Harden whips it to PJ Tucker, who is 6-of-12 on corner 3s in this series.

Houston has two shooters on the help side of the floor instead of one. That should make Utah’s assignments a little less stressful: Jae Crowder slides off Tucker, and Donovan Mitchell shifts down in between Tucker and Eric Gordon — “zoning up.” Once Harden makes his pass, Mitchell should probably sprint to Tucker, force him to drive or toss an extra pass to Gordon, and hope a fellow Jazz man rotates behind him.

Instead, Mitchell just sticks to Gordon. This is a common theme: Mitchell has been awful on the help side. He fails to zone up when he should, and hangs in no man’s land when he needs to scramble to an open guy.

Even scarier: Houston appears to have landed on a basic method of triggering Harden’s preferred passes and springing wide-open shooters.

That’s just mean. Capela is in the right dunker spot, with only one shooter on that side. The guy guarding that lone shooter has to help on Capela, and there is no one to help him.

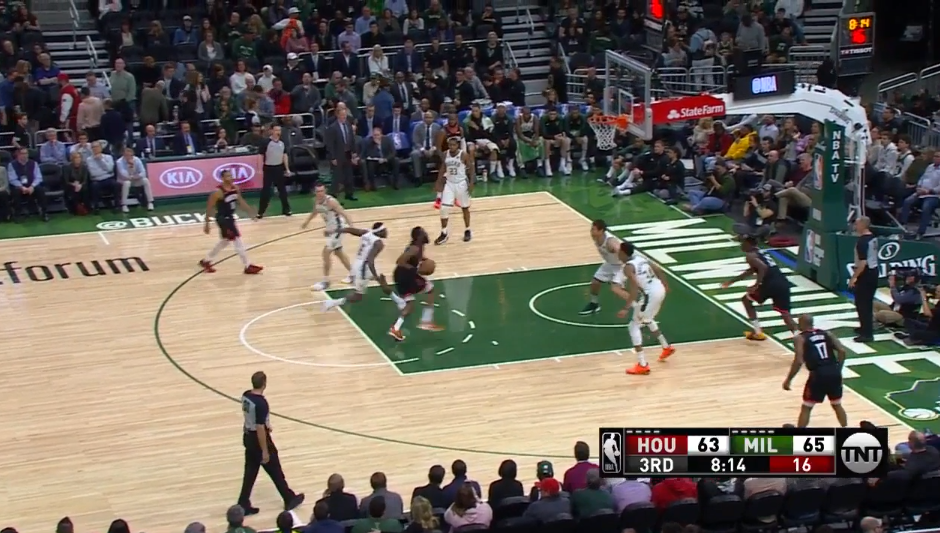

Houston didn’t just discover this alignment in the Utah series. Here it is from the Rockets’ game in Milwaukee last month:

Milwaukee managed this much better than Utah has. Look where Lopez is as Harden rises: in the center of the block/charge circle, in range to both bother Harden’s layup and get a fingertip on any lob to Capela.

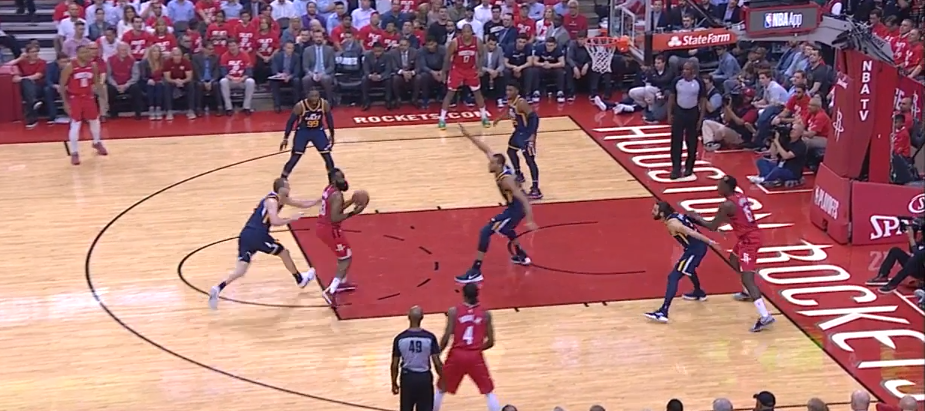

Look how far out Gobert is when Harden has barely crossed the foul line:

Gobert panicking compels Rubio into an earlier and more urgent rotation — leaving him miles from Danuel House Jr. when Harden slingshots the ball there.

With Lopez tethered to the hoop, Giannis Antetokounmpo can stay between Capela and Tucker. He covers that distance back to Tucker in one stride.

Houston has leaned on this setup — Capela on the right, one shooter flanking him — more against Utah. Harden manipulates the geometry to produce almost whatever shot he wants. Watch him at the very start of this clip point for Tucker to sidle up from the corner. Harden knows Thabo Sefolosha will follow Tucker, clearing the way for a lob to Capela; only a sensational read by Sefolosha saves Utah:

If the Jazz are going to continue forcing Harden to his right, Gobert has to do a better job holding the line — and holding close to the basket — until Harden is about to release the ball.

Utah has only a few other options. They could send help from the left side of the floor, but that seems impractical. They have another plan, and they already flashed it in Game 2. Watch that House 3-pointer again, but pay attention to Rubio — guarding House at first — just as Harden starts his drive:

He is pointing to House. Specifically, he is pointing for Joe Ingles to veer off of Harden and take House. Ingles does so too late. Here is Rubio pulling the same switch — also too late:

Ingles and Mitchell nearly execute it here, with Game 2 already out of hand:

Utah might try that gambit again. Also: Look at Ingles and Gobert bark at each other after Harden’s put-back. If I had to guess, I would say Ingles is miffed at Gobert for bolting the restricted area and leaping at Harden’s floater — leaving the glass naked. Gobert replies by mimicking Harden’s floater motion: What am I supposed to do? Let him shoot unchallenged?

Harden has the Jazz shook. He had them shook before the series even started. Rubio said after Game 2 that some players “haven’t been buying in 100 percent” to Quin Snyder’s strategy for defending Harden. Perhaps he was thinking about plays like the one in which Ingles failed to peel away from Harden, and onto House.

But every Jazz player has screwed up parts of Utah’s revamped scheme. That can happen when you defend in one style for 82 games, and overhaul it for a single playoff series.

Utah’s players now find themselves in unfamiliar positions, with unfamiliar responsibilities. Houston compounds the confusion by shifting the chess pieces around. They won’t overuse this Capela-on-the-right setup. They’ll toggle everything — Capela’s position, the location of their three shooters, where Harden starts his drive.

It is tempting to say Utah should abandon the “force Harden right” gimmick and defend him straight up. Both Rubio and Sefolosha showed glimpses of this in Game 2. But what does “straight up” even mean with Harden anymore? It would typically signify some sort of normal adjustment to pick-and-roll schemes — a trap, or a hard hedge.

But what is the adjustment when there is no pick? Maybe it is just playing Harden head-on, chest-to-chest. Will that accomplish anything? Will it make it any easier to stay in front of him? Probably not.

What do you do when he gets by the first line of defense? Some scouts suggest staying home on shooters and “letting Harden get his” — the same remedy you hear pitched for Antetokounmpo. But Antetokounmpo is a shaky shooter. You can play off of him. You can’t do that with Harden. He will be at the rim almost every time.

Perhaps Utah can play him straight up at first, make him expend energy dancing with the ball, and then shade him right late in the shot clock. Hooray?

You need incredible one-on-one defenders to play Harden straight up without yielding a parade of step-back 3s and layups: wings who are long, quick, and smart. Houston’s likely opponent in the next round has a few of those. Face a team like that, and Houston can revert back to a more screen-heavy attack — including rapid-fire double screens D’Antoni loves.

In the meantime, Utah should make Harden work more on defense; the Jazz can get him isolated against Mitchell whenever they want. If they get lucky, maybe they’ll lure Harden into foul trouble.

Utah might not find a solution. The Spurs created a blueprint for the league two seasons ago. Harden tore it up.