SPECTATORS IN JAM-PACKED Philippe Chatrier stadium at the French Open watched with disbelieving eyes. A hush gradually fell over the customarily buzzing international press workroom as reporters huddled around video monitors. Fans outside Chatrier on this chilly, cloudy day gathered wherever they could to get a glimpse of the live feed from inside a tournament office or hospitality lounge, often standing on tiptoes to see over those in front of them. One young woman sat like a child on her boyfriend’s shoulders.

The once unthinkable was morphing into reality: Rafael Nadal, winner of four straight French Open titles and 31-0 for his career at Roland Garros, was about to lose in the fourth round of the 2009 tournament to Bunyan-esque Swede Robin Soderling.

It was stunning. It was incredible. And the moment after Soderling won the match in four sets, the first thing that popped into the minds of many went something like: “Roger Federer has a chance to complete his career Grand Slam.”

By that point, Federer already had 13 Grand Slam titles — all earned at the three other Grand Slam venues. But Federer’s problem wasn’t clay. It was Nadal. Federer was the second-best player on clay to Nadal by a significant margin over other contenders, but the gap between the two seemed like the distance between Pluto and Jupiter. Nadal had thumped Federer in all four meetings at the French Open, three times in finals.

Now Federer was in with his best shot. Since he was almost five years older than Nadal, it was perhaps the only shot he would get. Everyone, including Federer, knew the pressure was on.

Last Friday in Paris, Federer — back at the Roland Garros terre battue for the first time since 2015 — said of Nadal’s 2009 fourth-round loss: “This is where these expectations started, when the journalists started saying it’s this year or never. From then on, the next nine or 10 days felt like forever. … I knew that instead of the tournament becoming easier, it was going to become more difficult because of the pressure.”

A decade later, the impact on his legacy is unmistakable.

“That could have been the last little ice cube — or glacier — weighing on his shoulders,” Tennis Channel analyst Paul Annacone, who would coach Federer for two years starting in 2010, recently told ESPN.com. “The last little thing keeping him from becoming the Federer he is today.”

NADAL LOST TO Soderling on Sunday, May 31, the eighth day of the tournament. On Monday, June 1, Federer would play his first match in the drastically altered landscape against a quick, electric shot-maker, Germany’s Tommy Haas. In Federer’s two previous matches, a pair of solid clay-courters in Jose Acasuso and Paul-Henri Mathieu had tested him, each winning one set.

Federer, 27 at the time, had beaten 31-year-old Haas nine times in 11 matches. Yet the Swiss icon and the lean German had much in common. Both were mercurial, graceful athletes who played at a brisk pace. Federer was a trifle smoother, Haas a mite more explosive. They had one-handed backhands that made aficionados drool, as well as knockout forehands. Haas had been a semifinalist at the Australian Open and a quarterfinalist at the US Open. The things that held him back had less to do with the X’s and O’s than with injuries and his emotions and moods.

Now the tournament director at the Indian Wells Masters, Haas recently told ESPN.com, “I was feeling physically stronger, coming off an injury at that event. And with Nadal out, everyone was talking ‘window of opportunity.'”

Haas had been getting good results with a new racket and had been as far as the fourth round at Roland Garros in the past, so he had confidence. “I always felt I matched up well with Roger,” Haas said, “even though he had proven many times that in the big moments when it counted more, he was just the more solid player.”

Their midday match was played amid alternating bouts of bright sunshine and shadows — the same conditions Federer had groused about following his previous win. At the start, Federer appeared muted, within himself, the opposite of his peppy opponent. “It was a big deal for me to be out there on Chatrier, in front of all those people once again,” Haas said. “I had the mentality that I had nothing to lose.”

And so it went. Boundlessly energetic, Haas raced, leaped and slid all over Chatrier, repeatedly getting the best of Federer in high-speed, high-risk rallies. Haas won the first-set tiebreaker when Federer slapped a feeble forehand serve return into the net. “He wasn’t taking full command of his opportunities,” Haas remembered. “He was making a few more unforced errors than usual, and his forehand wasn’t firing on all cylinders.”

Haas, meanwhile, was serving well. He felt confident enough in his groundstrokes to play from well back in the court, smacking powerful, penetrating shots and dictating with his forehand at every chance. The strategy earned him the second set as well, 7-5.

DOWN TWO SETS, Federer knew he was in trouble. He was searching for his game like a person who had mislaid his reading glasses. His attempts to find it were thwarted by Haas’ unrelenting aggression. Haas gave Federer no chance to pry open the match as the games rolled on to 3-all in the third set. The stress and strain on Federer had been steady, eroding his game until he found himself down break point at 3-4 — not quite a match point, but the next-best thing.

“I’d be lying if I said I didn’t think, at that point, ‘Hey, if I win this point I’m going to win this match,'” Haas said. “I’m going to serve him out.”

Federer missed his first serve; the tension mounted. The wildly pro-Federer crowd, taken out of the match early by Haas, fell silent. Head bowed, Federer bounced the ball a few times and began an elastic motion that produced a precisely placed kick-serve to Haas’ backhand. The spin and high bounce allowed Haas to wind up and crack the return crosscourt, deep to Federer’s backhand.

Cat-quick, Federer got a jump on the return. He was positioned to try one of the patented inside-out forehands that had let him down so often earlier in the day. He did not miss this time. Federer powdered the ball, his explosive strike lifting both feet from the ground. He knew on contact that the ball would fall good.

“Voila!” Federer grunted to himself in borrowed French.

“I feel proud that I was able to manage the pressure.”

Roger Federer

“I thought almost that it was my first good shot of the match,” Federer said after the match. “I knew I was going to look back on that shot. I knew if I come out of that game, I can create some opportunities later. That [shot] saved me on that day.”

“[Federer] took such a big cut that he landed with both his feet in [actually, behind] the doubles alley,” Haas said. “It looked like the ball could go out, but it caught the line — half an inch, an inch in.”

Haas added: “He was missing his forehand all day. The next thing you know, he makes that almost impossible first shot off the return. It kind of takes your breath away for a second.”

The shot ended up being the stick of dynamite that blew the door into the match off its hinges. Federer exclaimed and pumped his fist — for the first time that day, Haas thought. Also for the first time, Haas was aware of the din made by the passionate crowd.

Federer went on to hold, leaving Haas to serve at 4-all. Haas fought hard in that game, fending off one break point, but he was distracted. “I was kind of playing with my mind,” Haas said. “Thinking, ‘Wow, that ball should have gone out, I could be serving for the match.’ I knew I shouldn’t be thinking about that.”

Federer broke and held to win the set 6-4.

“I obviously had a little mental breakdown,” Haas said. “But now the crowd really got into it, and Roger was catching another gear. He went off in that fourth set.”

Federer won the fourth set 6-0. Haas regrouped briefly, holding to 2-2 in the final set. But deep down, he sensed his own doom. “When I was broken at 2-all in the fifth, I thought, ‘I’m not going to recover from this.’ I certainly didn’t,” Haas said. “It’s so tough when it’s slipping away, but that’s tennis. It stings; it stings a lot. “

Federer went on to win it, 6-7 (4), 5-7, 6-4, 6-0, 6-2. Despite the legendary fightback, he continued to feel an uncomfortable degree of pressure the rest of the tournament. He played well against Gael Monfils in the quarterfinals, but then became embroiled in an agonizing semifinal match with Juan Martin del Potro, finally winning it 6-4 in the fifth.

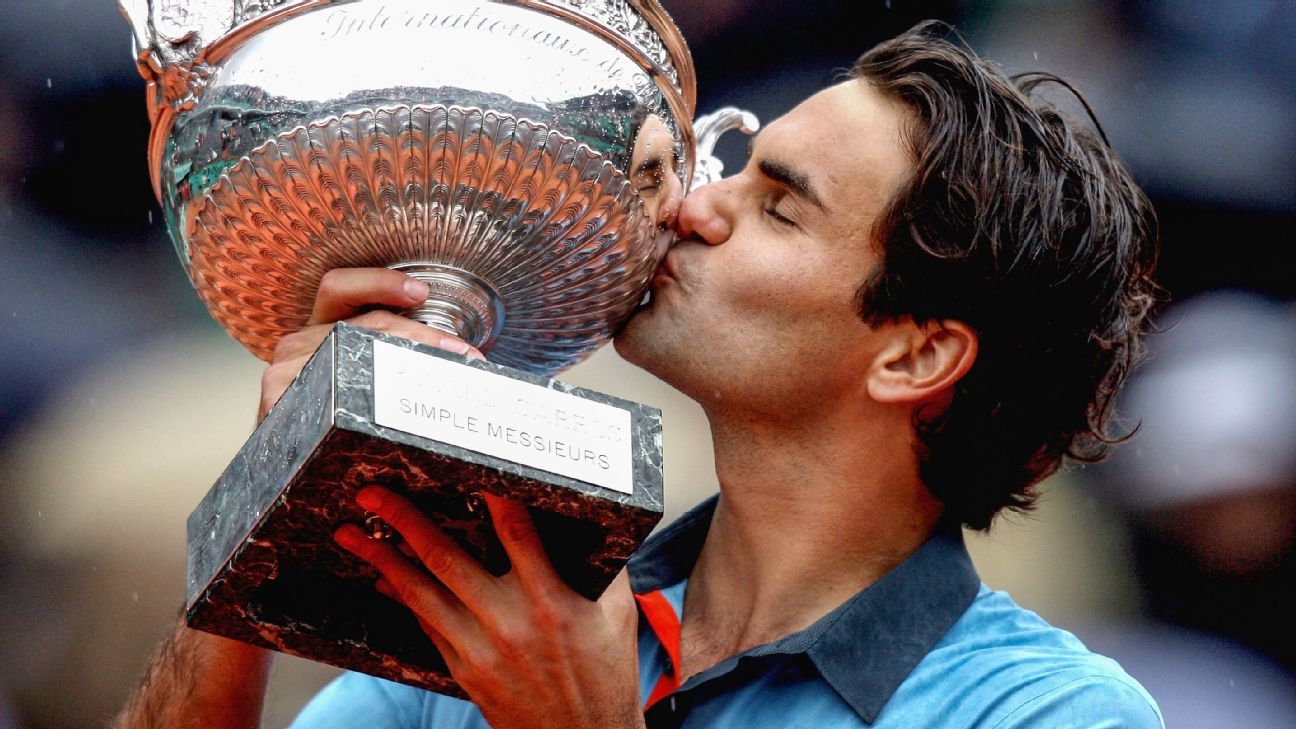

Soderling, the aggressive Swede who had jolted Nadal a week earlier, wasn’t able to impose that big game on Federer in the final. Better in every department if not quite as powerful, Federer cruised, 6-1, 7-6 (1), 6-4.

It was finally over for Federer. The anxiety was dispelled, the strain relieved, the mission — a French Open title and completion of a career Grand Slam — accomplished.

FEDERER’S 2009 WIN in Paris — 10 years later still his only title at Roland Garros — plays an outsized role in the current, lively GOAT debate. As ESPN analyst Pam Shriver said, “It’s a different conversation if he doesn’t win that one. But you also sensed there was no way he was going to play his career and not win the French.”

True, but when Nadal returned in 2010, he won the title five years running. Federer had one more chance to win the French without having to deal with Nadal. In 2015, Nadal was beaten in the quarterfinals by Novak Djokovic, ending a 39-match win streak that began immediately after his 2009 loss to Soderling. But Federer also lost in the 2015 quarterfinals, falling to eventual champ and countryman Stan Wawrinka.

It’s hard to say which was greater after the 2009 final in Paris — the pride Federer took in his achievement or his feeling of relief.

“This one was hard,” Federer said of his triumph a few weeks later, at Wimbledon. “I was mentally drained because I felt like I had to play like four finals at the end of Paris because of the pressure.”

“He played with a lot of nerves,” Haas said. “After, when we shook hands, I could see how much it meant to him. You could see how relieved he was, after having to dig so deep.

“That shot, he just decided when he had the opportunity he would line it up and just kind of go for it, which is what he did,” Haas added. “And you kind of go, ‘That killer instinct, that’s the mentality of a champion — not to play it safe but to trust yourself to do something special.'”

As dazzling and crucial as that bold inside-out forehand was, Federer cherishes the 2009 triumph mostly for what it said about his steel as a competitor. On Friday, contemplating this year as the 10th anniversary of his French Open title, Federer said: “I feel proud that I was able to manage the pressure.”

Federer is still at it, dealing with pressure in its myriad guises. If they both continue to play well at this year’s French Open, Nadal looms in the semifinals. Federer wouldn’t have it any other way.