HOUSTON — The Houston Astros did something Wednesday night that for any other team would have registered as benign. Juan Soto, the 20-year-old wunderkind who hits cleanup for the Washington Nationals, was due up. With first base open and runners on second and third, the Astros intentionally walked him. For 173 games between the regular season and the playoffs, Houston had not issued a single intentional walk. But this was the top of the seventh inning in Game 2 of the World Series, when nothing made sense.

A guy who entered the night 1-for-23 in October crushed a go-ahead home run off one of the best pitchers of his generation. Three consecutive singles were feathered about the diamond, none leaving the bat fast enough to draw a speeding ticket on the Pickle Parkway. A sacrifice bunt, anachronistic though it is, was laid down. And — hand on heart, this is true — a team went 10 batters without striking out once.

The path to six runs can snake in endless permutations, yet this one — the blitzkrieg that led the Nationals to a 12-3 blowout and a 2-0 series advantage as they return to Washington D.C. for three games — was wild by any standard. Over the course of 33 pitches, the Nationals turned a tense, taut pitchers’ duel between their Stephen Strasburg and the Astros’ Justin Verlander into a blowout. It wasn’t a deluge. It wasn’t some surgical deconstruction of a lesser. It just sort of materialized, not a gift — the Nationals don’t need those — but a perfectly timed stroke of fortune.

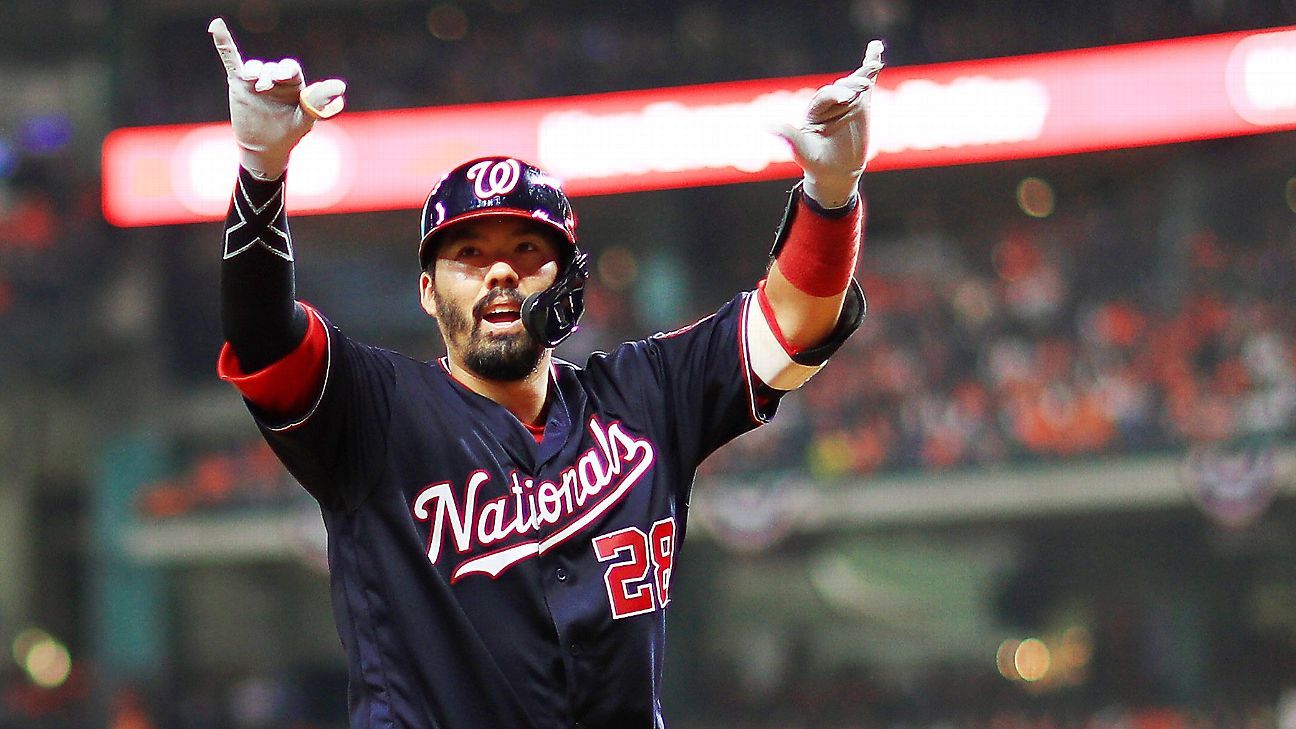

It began with a fastball, 93.5 mph, top of the strike zone, middle of the plate. Verlander, the Astros’ co-ace, had cruised the previous five innings after a shaky first and was trying to maintain a 2-2 score. Kurt Suzuki, the Nationals’ catcher, he of that .043 batting average, took the 100th pitch of Verlander’s night out to left field. The score was no longer tied. One night after beating Gerrit Cole, the other half of Houston’s seemingly unbeatable duo, the Nationals once again had silenced the crowd of nearly 44,000 at Minute Maid Park.

This has become customary. The Nationals last lost a game on Oct. 6. They had won four consecutive road playoff games heading into Wednesday. Improbable things happen in October, which means, sure, Kurt Suzuki — a 36-year-old catcher in the twilight of his career — can launch a home run off Justin Verlander.

“I can’t remember the last time I barreled a ball up like that,” Suzuki said. “It felt great. It felt like months ago — probably was months ago. It felt great.”

Fine. It can end there, with one odd event. But then Verlander issued a seven-pitch walk to Victor Robles. Now, Robles, a rookie center fielder, is a good player and should be great. He does many things well. But walking is not one of them. In 617 plate appearances this season, he walked 35 times. He was hit by a pitch almost as many times (25) as he walked. Until the seventh inning, he had come to the plate 22 times this postseason and not drawn a single walk.

“It’s very difficult to hit after a solo home run. Especially in a big game,” Nationals right fielder Adam Eaton said. “Sometimes you want to do too much, you want to hit another homer, that type of deal, keep things going. To walk there — for me, that’s the play of the game.”

Robles’ walk chased Verlander. In came Ryan Pressly, who took leadoff hitter Trea Turner to a full count before walking him. Eaton laid down a bunt to advance the runners, which was on brand — he led the National League with nine sacrifices this season — but completely foreign to 2019 baseball. Position players totaled 342 sacrifices all season — one every seven or so games.

Nationals manager Dave Martinez called for the bunt because he wanted to scratch across an insurance run, especially with Strasburg finished after six innings and the Nationals’ bullpen ill-equipped to register nine high-leverage outs. Anthony Rendon, their star third baseman, flew out to shallow center field, setting the stage for Astros manager AJ Hinch to call for the intentional walk. Hinch weighed Pressly’s reverse platoon — he held left-handed hitters this year to a .124/.165/.196 line during the regular season — and chose to have him face Howie Kendrick.

1:10

Kurt Suzuki breaks the tie with a solo homer, and the Nationals push across six runs in the top of the seventh inning.

“I felt it was our best chance to limit their scoring,” Hinch said, “and instead it poured gasoline onto a fire that was already burning.”

The embers were on first, second and third. Kendrick yanked a second-pitch slider from Pressly to the perfect place, right on the lip of third baseman Alex Bregman‘s glove. Bregman couldn’t corral the ball, then missed when he stabbed at it with his throwing hand. There was the insurance. That, Rendon said, was the biggest at-bat of the inning. “If he gets out right there,” he said, “we don’t get those runs.”

Actually, according to Robles, the biggest at-bat of the inning was the next one, which belonged to Asdrubal Cabrera. He joined the Nationals on Aug. 6, long past their dreadful start that nearly resigned them to sitting out the postseason. He started Game 2 with three consecutive strikeouts against Verlander. Against Pressly, he hung with a low-and-inside slider and guided it into center field, with the ball leaving the bat at 75.7 mph. Two more runs scored. It was 6-2.

Hinch stayed with Pressly. He worked ahead of Ryan Zimmerman, then lost a breaking ball in the dirt that moved the runners up to second and third. Zimmerman stared at another ball to bring the count full before tapping a curveball down the third-base line. The exit velocity: 62.8 mph, paltry and meek. “You need the soft-hit ones to be outs,” Verlander said.

They weren’t in Game 2. Bregman barehanded the roller, attempted to throw to first and sailed the ball up the line. That allowed two runs to score, extended the deficit to 8-2 and brought the order all the way back to Suzuki, who faced reliever Josh James and grounded out to end the inning.

“Luck’s gonna happen when it happens,” Kendrick said.

There was luck. He isn’t wrong. There also was skill. The Astros might have been the best contact-hitting team in the major leagues this season, but the Nationals weren’t far behind. Their swinging-strike percentage ranked third. In those 33 pitches among Verlander, Pressly and James, Washington hitters swung and missed just three times — a touch less than their 9.5% swinging-strike rate during the season and well under the 12.1% average across MLB. Three strikeout pitchers didn’t register a single K.

“Any time you make contact is a good thing,” Kendrick said, “because when you put the ball in play, anything can happen.”

It wasn’t just anything that happened. Everything happened. The improbable home run and the just-as-improbable walk and the obsolescent bunt and the unlikely intentional walk and the dink and the dunk and the bleeder. It was the wild, stupid, beautiful seventh inning in which nothing made sense, which was perfectly OK by the Washington Nationals.