The call came in the middle of dinner. Paul George had been text-messaging throughout the meal — not an uncommon occurrence at this point in late June, as the NBA approached one of its most audacious free-agent signing periods. But when the call came in, he got up from his table at Catch LA, an upscale seafood restaurant, to take it privately.

That’s when his friends knew something was afoot.

“I knew it was something. Something big,” says Alex Jackson, George’s best friend from high school. “Because I can kind of tell with him. He gets quiet, looks around because something is on his mind.”

The caller on the other end of the line was Kawhi Leonard, the soon-to-be free agent who had just won his second NBA Finals MVP award in leading the Toronto Raptors to the title. Now he and George were surreptitiously discussing joining forces on a new team, the LA Clippers, a move that might reshape the balance of power in the NBA for years to come.

It would be an incredible turn of events — nearly inconceivable in its complexity and degree of difficulty. George was under contract to the Thunder for two more years. “It just didn’t seem likely,” George says.

But nothing is impossible in this era of player empowerment in the NBA. Leonard and George had both come into the height of their powers — and leverage — at the exact moment that their hometown team had been positioning itself to take advantage of it.

When he rejoined his two friends, Jackson and Myles Williams, at dinner that night, George tried to keep things to himself. They were the types of friends who knew not to ask.

“But after a little bit,” Jackson says, “he was like, ‘I gotta let it out, man.'”

I think I’m going to come home.

“P definitely keeps that one mood,” Williams says. “But deep down inside, I knew he was excited.”

If George and Leonard could pull this off, the Clippers would become an instant title contender. But it was more than that for George. A lot more than that.

“[People] think it was a basketball move,” George says. “And for a lot of reasons, it was a basketball move. But that’s not where it comes from.

“It was a lot deeper than me coming here for basketball reasons.”

Ramona Shelburne helps tell the story of why Paul George decided to join the Clippers and how close he is with his family. Produced by Mike Farrell; edited by Kevin Burns.

THE BATTLE FOR L.A.’s basketball soul hasn’t really been much of a battle until now. The Lakers have 16 titles and a veritable Mount Rushmore of Hall of Famers. And the Clippers have … also been based in Los Angeles.

But this is a real rivalry now. As soon as the 29-year-old George and 28-year-old Leonard teamed up on the Clippers — the partnership became final on July 6, when Leonard signed with the club and George was traded to it — you knew the Lakers and Clippers would be positioned as the marquee game on Christmas Day.

It is a taut game throughout, with Leonard and George trading haymakers with LeBron James and Anthony Davis. But the Clippers rally in the final minutes to nip their more glamorous rivals 111-106.

George lingers on the Staples Center court long after the game, soaking in the atmosphere.

Fans congregate by the tunnel leading to the Clippers’ locker room, the group swelling as red-coated security guards try to keep them from blocking George’s path.

It could have been uncomfortable, with fans pushing and shoving to get his autograph or capture some other piece of him. But a collective understanding has taken hold of the crowd. Paulette George’s wheelchair is in the tunnel, but she and her husband, Paul George Sr., are still four rows up in the stands.

In full uniform, George goes to his mother, wraps his arm around her, shielding her from the crowd, and helps her walk slowly down the stairs.

No one touches them.

“I think the fans … they get it,” George says. “And they allowed for me to have that moment with my mom.”

George has always been close to his mother. As a kid, he was her “sidekick,” he says, holding her hand as they went on errands around Palmdale, California. She called him “Man” because he was bigger than all the other kids his age, and because, of her three children, he was her only son.

“My mom was everything,” George says. “She made sure the house was organized, made sure our homework was done. She was the enforcer. My dad is more like me, laid-back.”

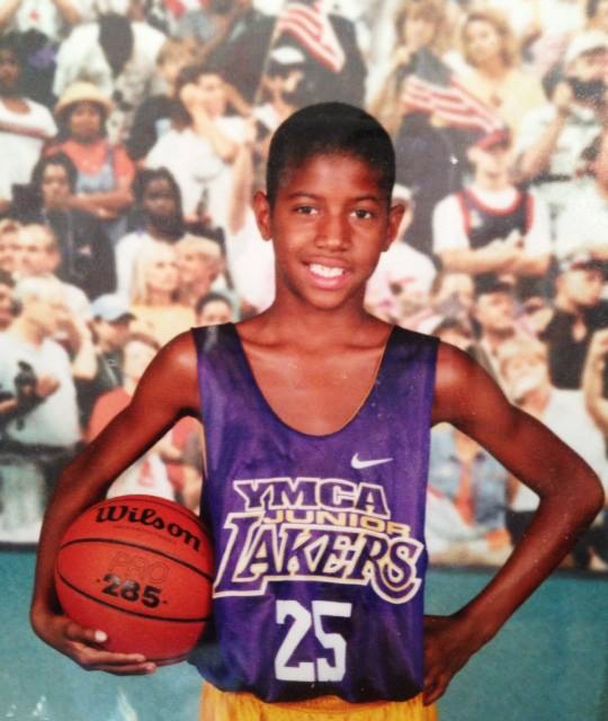

George grew up a Kobe Bryant fan in Southern California, close with his mom (she called him her ‘sidekick’), dad and two sisters. Courtesy George Family

Then one night she got a bad headache, and everything changed. A blood clot had traveled up from her calf, cutting off oxygen to her brain and causing a stroke. She was 36 years old. Paul was 6. He was outside playing basketball when the ambulance pulled up and carried his mom out on a stretcher. He was terrified.

“She was almost at, like, a vegetative state,” George recalls of the early days in the hospital. “She was unrecognizable, she couldn’t communicate, she couldn’t talk, she was going blind.”

Paulette could hear everything happening around her but couldn’t talk or move. Eventually, she learned how to communicate in other ways.

“She would put her hand up, and the doctors would tell her to squeeze it, squeeze her hand,” George says. “That was enough for me. I knew she was aware. She was still with us.”

It took years of constant therapy to relearn how to walk and talk. During one of her stays in a rehabilitation facility, she developed a high fever caused by pneumonia and nearly died.

“My mom is all about defying odds, because odds was stacked up against her,” George says. “They said my mom wouldn’t walk again. They said my mom wouldn’t talk again. They said she would be completely paralyzed, that her vision wouldn’t come back. And she defied all of that.”

Paul Sr. worked two jobs to provide for the family while his wife recovered. Older sisters Portala and Teiosha stepped up to help raise their brother. By the time Paul was a freshman at Knight High in Palmdale, his mother was able to attend his games. Knight High equipment manager Jimmy Segura put a special chair on the court for her, where she’d sit with Paul Sr.

“They came to every high school game,” Segura says.

It was still difficult for Paulette to move around. But her children gave her motivation to push herself. The way to regain her independence and abilities was to keep trying to do as much as she could. Walk up a few stairs, even if it took 10 minutes. Have Paul Sr. park the car a little farther away. Walk rather than use the wheelchair. Cut every article written about Paul out of the newspaper, then put them into a scrapbook.

Simple tasks, taken away by her stroke. But so precious once she regained them.

When Paul went to Fresno State for college, his parents moved from Palmdale to Fresno — about three hours north — so they could keep going to his games. But when Paul was drafted by the Indiana Pacers in 2010, traveling to his games got considerably harder.

“My mom doesn’t complain,” George says. “But having conversations with her, it’s hard for her to get on planes and travel.

“For me to be able to come to her and make it a lot easier for the travel on her and my dad, that was one of the biggest reasons I wanted to come back and play at home.”

AFTER THE NEWS conference when the Clippers introduced George and Leonard, coach Doc Rivers walked with George through the audience, and a theme quickly emerged.

“It was funny,” Rivers says. “One George, two George, three George. Holy cow! His sister, sister’s husband, his dad, his mom … and they’re at every event we’ve had. They’re all there.”

There are even Georges around Paul George who aren’t related to him. There’s his security guard, Vincent George, whom he met in Oklahoma City. “He calls me Unc,” Vincent George jokes. There’s “Coach George,” the assistant coach from Knight High in Palmdale, who taught him to dunk by jumping over trash cans. “My name is actually J-O-R-G-E Swayne,” the coach says with a laugh. “But he just calls me Coach George.”

It’s a lot. And to some — including George’s coach — it would be a distraction.

“Like, I love Chicago,” Rivers says of his hometown. “But I have no interest in playing there. No way — all the people, the ticket requests.”

But George prefers it this way.

“[He] actually wanted to come home and to dive into the distractions instead of running away from them,” Rivers says.

In Indiana, George had a house right on Geist Reservoir, where his friends and family stayed, fishing while he was at practice, then frying up whatever was caught for dinner. George kept in touch with friends via text message and nightly video game sessions.

But those visits and virtual hangouts aren’t the same as living in the same city. And after nearly a decade away from home, George’s friends could sense him yearning for that support.

“We didn’t get to see him a whole lot,” says Dallas Rutherford, one of George’s closest friends. “We’d go fly out there, but obviously we’re all older and have our own lives. So it’s not like we can be out there 24/7.”

Now, in Los Angeles, George has about 70 relatives who regularly come to events, games or family gatherings. There is an even larger group of friends who are now able to show up and support him too.

“I think he’s at that point in life where he was like, ‘I know who my friends are. I know who came to visit me in Indiana. I know who came to visit me in Oklahoma,'” Williams says.

“Like, ‘These are my people.'”