In 2006, less than an hour after Tony La Russa had won his first World Series as the manager of the St. Louis Cardinals, he was greeted in the hallway at Busch Stadium by an iconic figure.

“Bob Gibson just shook my hand,” said La Russa, who had won a World Series in Oakland, and won nearly 2,500 games by that time, yet he was glowing, in awe of what had just happened. “I just got welcomed to the club by Bob Gibson.”

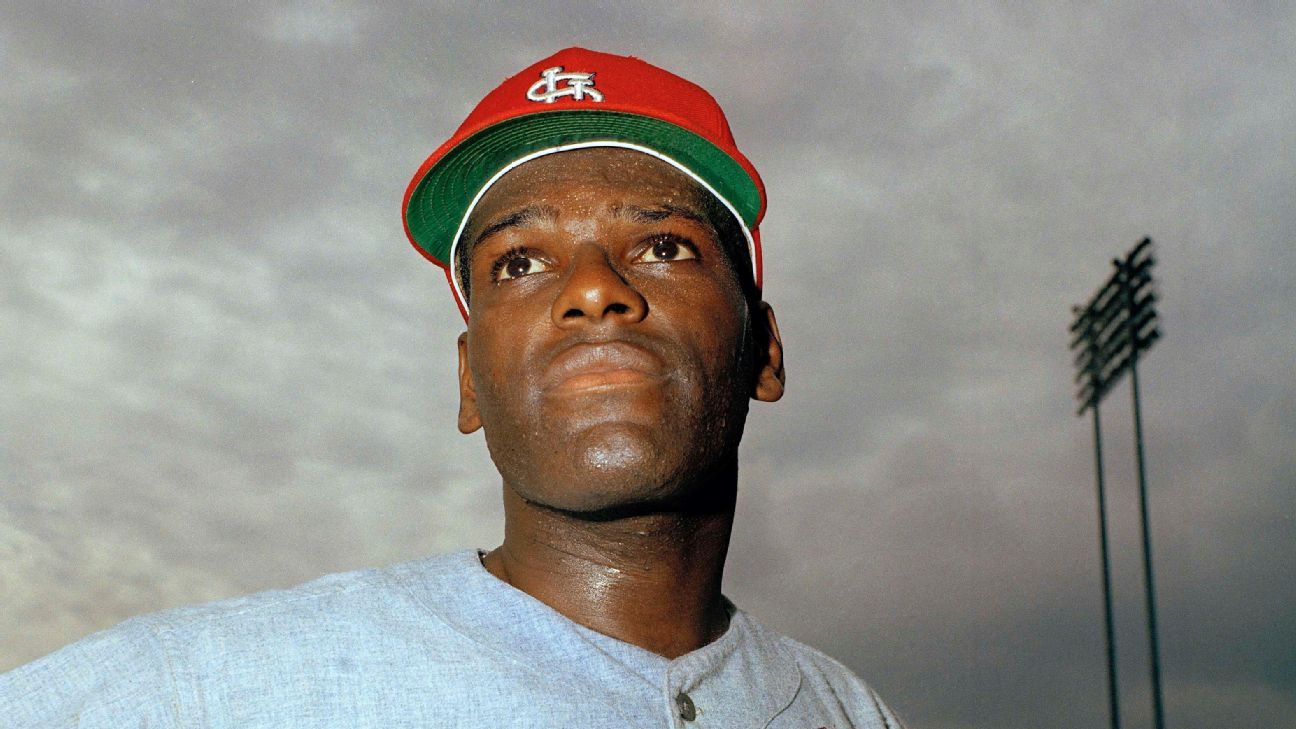

That’s the reverence paid to Bob Gibson, not just in St. Louis, but across major league baseball: something, or someone, becomes official when endorsed by Bob Gibson. He was one of the greatest pitchers of all time, he was arguably the greatest athlete ever to pitch in the big leagues, and when it came to competing, no one was more ferocious than Gibson.

Gibson, who announced in July 2019 that he had pancreatic cancer, died Friday at age 84.

“I loved facing him because he wanted to win so much,” said Frank Robinson, a fellow Hall of Famer. “If I won the battle against him, I knew that I had beaten the absolute best.”

Gibson went 251-174 with a 2.91 ERA for the Cardinals from 1959 to 1975, making him, without a doubt, the greatest pitcher in Cardinals history, and after Stan Musial, the greatest player in Cardinals history. Gibson won two Cy Young Awards, in 1968 and 1970, the first Cardinal to win the Cy Young, the only Cardinal to win the award twice.

In his 1968 season, he posted a 1.12 ERA, the lowest by any pitcher in the live ball era (since 1920), and the second lowest to the Cubs’ Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown (1.04 in 1906) in the modern era (since 1900). That season, Gibson threw 47 consecutive scoreless innings, which, at the time, was the third-longest streak in history. He completed 28 out of 36 games, and he was removed for a pinch hitter eight times: meaning, he was not replaced on the mound, in mid-inning, by another pitcher all season. He threw 13 shutouts, he had 56 in his career, nearly as many as Greg Maddux and Tom Glavine had combined.

Gibson made nine All-Star teams.

“I hated the All-Star Game,” Gibson said years after retirement. “I hated having to talk to guys that I spent the rest of the season trying to kick their ass. They were the enemy to me.”

“Gibby was no fun at the All-Star Game,” Willie Mays said, smiling. “He didn’t talk to anyone.”

“No pitcher I faced competed like Gibson,” Hank Aaron said. “He hated you when he pitched.”

Gibson especially hated hitters, it seems, in the postseason. He made nine starts, all in the World Series, and completed eight, went 7-2 with a 1.89 ERA. In 81 innings, he gave up 55 hits, walked 19 and struck out 92.

In Game 7 of the 1964 World Series, he beat the Yankees 3-0.

In 1967 against the Red Sox, Gibson won Games 1, 4 and 7, making him the first pitcher to record a complete-game victory in a Game 7 of two World Series. In Game 1 of the 1968 Series against the Tigers, Gibson struck out 17, which remains a postseason record.

“We had no chance,” former Tiger Norm Cash said. “That was the best stuff I had ever seen.”

Gibson was the second pitcher — joining the great Walter Johnson — in major league history to reach 3,000 strikeouts, a distinction Gibson held at the time of his retirement in 1975. The Cardinals retired Gibson’s uniform No. 45 before his final season had even ended.

“The best I ever played with,” ex-teammate Mike Shannon said. “There was no one like Gibby.”

Gibson was perhaps as good an athlete as has ever pitched in the major leagues. He was a great hitter with 24 home runs, a mark only seven pitchers surpassed in the game’s history. In 1970, he joined a select group of pitchers who won 20 games in a season in which he batted .300. Gibson was also one of the best fielding pitchers of all time, winning nine Gold Gloves.

Gibson was an all-state basketball player in high school in Omaha, Nebraska, then averaged 22 points a game his junior year at Creighton University. He signed with the Cardinals in 1957 but delayed his baseball career so he could play a year for the Harlem Globetrotters.

“Playing basketball made me a better baseball player,” Gibson said. “It helped with my footwork, my hand-eye coordination, my stamina. I loved basketball just like I loved baseball.”

And he showed that love by competing, by overpowering hitters, by intimidating hitters.

“If you showed him up in any way on the field,” Robinson said, “you were going down.”

“I was told by Hank Aaron never to mess with Bob Gibson,” Nationals manager Dusty Baker said. “I was told never to stare at him, or talk to him, or smile at him. And if he hit you with a pitch, I was told never to charge the mound because he would beat your ass.”

Tim McCarver caught Gibson for many years, becoming close friends with him. And yet, when McCarver went to the mound to talk to Gibson, he wasn’t always welcomed kindly. McCarver famously said that Gibson was particularly ornery during one trip to the mound, and said to McCarver, “The only thing you know about pitching is you can’t hit it.”

Gibson retired after the 1975 season in part because a knee injury took away his greatness, and he wasn’t about to pitch to an ERA above 5.00. In his final seasons, Gibson had a brief confrontation with Pirates third baseman Richie Hebner, but Gibson never got to finish it on the field. In retirement, he saw Hebner on an elevator, and only half-joking, went after him.

That was Bob Gibson, a fighter, a ferocious competitor, to the end.