TALLAHASSEE, Fla. — As players usher in a new era in collegiate sports Thursday with the ability to make money off their name, image and likeness for the first time, Florida State quarterback McKenzie Milton and Miami quarterback D’Eriq King entered the marketplace with a unique business partnership.

Just past midnight, Milton and King signed on as co-founders of Dreamfield, an NIL-based platform focused primarily on booking live events for student-athletes, including autograph signings, meet-and-greets and speaking engagements. Milton and King will be the public faces of Dreamfield and will recruit other athletes to use the platform.

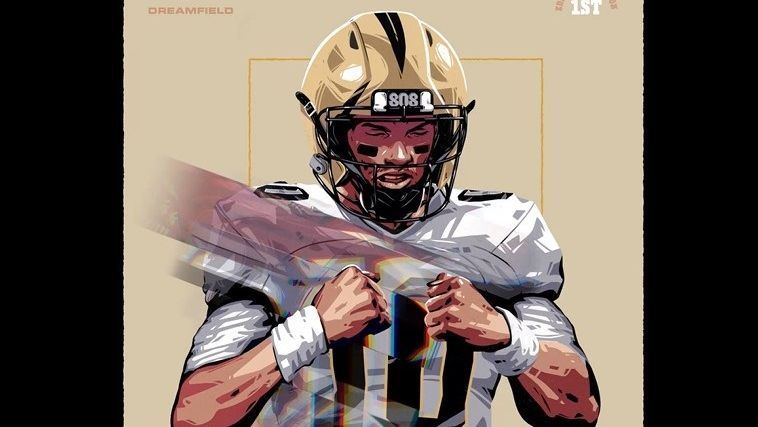

In addition, Dreamfield plans to take on the increasingly popular NFT (non-fungible token) market, with Milton on its first digital card set to go to auction July 6. The Milton NFT is believed to be the first for an active collegiate athlete. Plans are in the works for King to have his own NFT debut in late July.

“This is an opportunity for me to get my foot in the door to start being an entrepreneur, but this is also something that I’m passionate about, helping college athletes monetize off their name, image and likeness,” Milton told ESPN.com. “This should have been something going on for a while, but now it’s here, and it’s a cool opportunity.”

Florida lawmakers were the first group to set a July 1, 2021, start date for allowing college athletes to profit from their NIL. Nearly a dozen states have followed Florida’s lead and will have laws going into effect Thursday. The NCAA waited until Wednesday to officially adopt rule changes that open similar opportunities for all college athletes. The association offered only very loose guidelines to schools in states without a law, leaving many athletic departments scrambling to come up with their own policies for how to regulate and monitor their athletes’ deals.

Student-athletes in states with legislation have at least been given a framework based on the law, and more time to prepare and begin thinking about how to make money. This new era has led to the formation of multiple platforms for student-athletes to use to begin profiting off their NIL. While players must still adhere to NCAA compliance rules that prohibit direct pay-for-play arrangements, most of the focus on profitability has centered on autograph sessions, camps, local appearances, social media influencer status and possibilities for endorsement deals from a range of companies and businesses.

Where Dreamfield wants to stand apart is in the NFT arena. In this emerging tech market, an NFT is essentially a unique form of digital art that cannot be replicated and is purchased using cryptocurrency. Topps offers NFT baseball cards now. Patrick Mahomes and Rob Gronkowski released highly popular NFT cards in March. The Gronkowski set generated more than $1 million. In April, shortly after his college career ended, Iowa’s Luka Garza created his own NFT that sold for $41,141 at auction.

The illustrator of the Gronkowski series, Black Madre, partnered with Dreamfield to make Milton’s NFT.

“NFT creates a new way of looking at sports collectibles,” Black Madre told ESPN.com. “It’s an exciting moment. We were very fortunate that our first NFT project was a huge success and that opened so many doors for us. McKenzie Milton’s NFT card was a very special one. During the process of creating this card, we’ve learned a lot about him. He is truly an inspiration, and it was an honor to play a small part in telling his story.”

Milton provides a unique story. After leading UCF to an undefeated season in 2017, Milton suffered a devastating knee injury in 2018 that nearly forced the amputation of his right leg. The quarterback has worked the past three years to try to play again, transferring to Florida State in January in the hopes of winning the starting job.

The NFT card shows his transformation, starting with a still image of Milton wearing black and gold, and then morphing into a graphic of Milton wearing garnet and gold. The NFT is also careful of the rules — only the UCF and Florida State team colors are shown. Players in Florida are not allowed to use school logos or other copyright-protected material to make money unless they have permission from the school. To make the NFT even more unique, Dreamfield plans on embedding a video message from players featured on the digital card. Dreamfield is set to auction off 24 limited edition Milton NFTs, each serialized with a unique number in the collection, starting next Tuesday.

“We want to be like the new Topps, or Stadium Club, of digital, because right now, anyone that’s doing NFTs, they’re not doing it under a brand, they’re doing it independently,” said Luis Pardillo, one of the founders of Dreamfield and its CEO. “So I think there’s an opportunity to put it all under an umbrella and really drive it.”

Pardillo, a UCF graduate, met Milton when he was still at UCF and reached out to get his thoughts on NIL before Dreamfield was formed. Pardillo eventually partnered with another UCF grad, Andrew Bledsoe, and Aaron Marz. As they built up their company, they decided it made sense to offer equity to Milton once July 1 rolled around, as a way to show their business had student-athletes’ interests in mind.

Milton brought King onboard. The two have formed a close relationship since their time playing in the American Athletic Conference (King was at Houston before he transferred to Miami). The NFT idea especially appealed to King.

“We are entering a new era of technology that allows sports trading cards to move from the physical realm to the digital one, and I am proud to be on the forefront of this change,” King said in a statement to ESPN.com. “Being one of the first college athletes in history to have a high-quality NFT created in my likeness is a dream come true, and to help other athletes be memorialized in digital art through Dreamfield is a big reason why I helped create this company.”

Though King and Milton now play for rival schools, their quest to help in the fight to make NIL a reality allows them to share common cause.

“We’re trying to do something that’s bigger than us,” Milton said. “That’s advocating on behalf of all these athletes, and it’s bigger than the sport. It’s about creating a platform. It’s about using your name, to be able to help yourself, help your families, help your team. We’ve been handcuffed for so long, but now it’s given us the opportunity to expand our toolbox not just as athletes, but as businessmen, entrepreneurs, and all sorts of things. So I think it’s going to be great for college athletes to continue to explore new things that garner our interest.”