New York Mets owner Steve Cohen is an avid collector of art, his collection of Picasso and Doig and others reportedly worth many hundreds of millions of dollars. But one of his favorite pieces is round: the baseball that rolled between the legs of Bill Buckner to end Game 6 of the 1986 World Series to give the Mets their greatest victory ever.

The ball had been sold repeatedly, and when it became available in 2012, Cohen was told by a business associate that it would probably cost something in the range of $100,000 to $150,000, as he explained last year to SNY. “All right, I’ll do it,” Cohen recalled saying. “It’s a great moment in Met history. ‘Buy it.'”

A deal was struck on Cohen’s behalf, and it wasn’t until afterward that Cohen asked about the final price — $410,000, as it turned out. He remembered not being happy about it at the time.

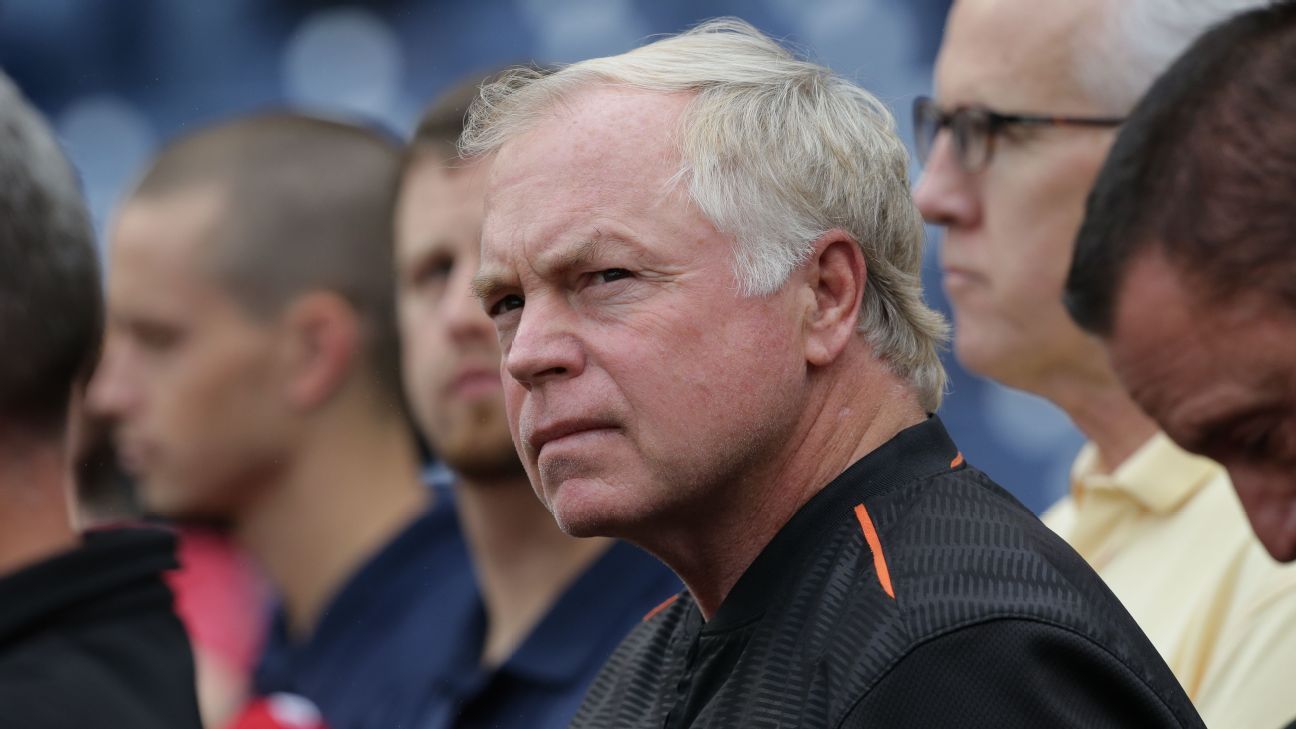

But in the end, Steve Cohen got exactly what he wanted, and an episode that mirrors how he’ll continue to run his baseball team. There was one managerial candidate available who checked every need for the best possible Mets hire — an experienced manager who would have instant credibility with players, was considered an excellent tactician and someone who had worked in New York — and this is how Buck Showalter was hired. A win-now manager for a win-now team operated by a win-now owner.

When Cohen purchased the Mets, he had suggested that he would win a World Series within three to five years. After Year 1 — the 2021 season — was a complete disaster, Cohen has doubled down, paying a record amount ($130 million over three years) for future Hall of Famer Max Scherzer. The Mets’ clubhouse culture was perceived to be a problem last year, so Cohen’s new general manager paid high prices for Eduardo Escobar and Mark Canha, two players known to strongly influence teammates. The Mets needed a center fielder, so Cohen OK’d the signing of the best available center fielder, Starling Marte, to a staggering four-year, $78 million contract.

Rival executives estimate that hiring Showalter will cost the team between $3 million and $5 million annually, or three to five times what the other candidates, Joe Espada and Matt Quatraro, might have earned as first-time big league managers.

Really, any choice other than Showalter would’ve been fraught with risk, because of the enormous risk that the 2022 Mets will bear. The best chance for Cohen and Eppler to win now was to spend big this winter, but it could all go sideways. Ace Jacob deGrom hasn’t pitched since the middle of last season, and according to team president Sandy Alderson, he suffered a UCL sprain last summer — something that deGrom subsequently denied. Scherzer turns 38 in July, and his chance for injury increases from year to year. Robinson Cano is 39 years old and missed all of last season because of a PED suspension. Marte, Canha and Escobar are all closer to the ends of their respective careers than the beginning.

And if injuries manifest — especially within that extraordinarily talented but perhaps fragile rotation — and the ’22 season turns out to be another mess, it’ll be a lot easier for Cohen and Eppler if they do so with Showalter as their manager. If they had passed on Showalter and picked a newbie, they would have set themselves up for an avalanche of second-guessing and criticism in a bad year.

Now, with Showalter, Eppler doesn’t have to worry about how his manager will handle questions about injuries. He doesn’t have to wonder how Showalter will react to a losing streak, to talk-radio criticism. Rather, Eppler can just focus on team-building in the big leagues, on bolstering the infrastructure of the organization, on stocking a farm system that has effectively been protected by Cohen’s spending this winter, because the Mets haven’t needed to trade prospects to improve.

And there is no mistake about this: Showalter is viewed as an excellent manager. Like Craig Counsell of the Brewers and former Giants manager Bruce Bochy, Showalter generally excels in keeping relievers fresh through disciplined deployment. (Yes, he did make a mistake in not using Zack Britton in a playoff game against the Jays.)

Showalter is 65 years old and first managed in 1992, about a decade before teams began to seriously explore the analytics universe, so he has been stereotyped as Old School, as someone resistant to the numbers generated by front offices. This is not right: When Showalter was at ESPN, anyone who worked alongside him — and I was one of those — knew that he was fascinated by the numbers, but also wanted them presented within proper context. During his time with the Orioles, a young analyst led a conversation about the perceived defensive deficiencies of catcher Matt Wieters, painting a picture of someone who was a bad catcher. Showalter defended Wieters with a series of rhetorical questions, which is how Showalter often makes his point.

Well, how were those ugly pitch-framing numbers weighted down by the fact that Wieters regularly worked with Ubaldo Jimenez, one of the sport’s most erratic pitchers, and Zack Britton, whose sinker moved so dramatically and so hard that it was just about impossible to frame?

What do the metrics say about how Wieters handles a struggling young pitcher, settling him and guiding him through difficult moments?

What do the metrics say about what it means to have a leader in a linchpin defensive position?

His counter argument was, of course, that numbers alone couldn’t fully define the value of any player or decision given all of the variables involved. Showalter’s belief then — and now — is that the most effective use of the numbers as a tool is in helping players understand how they can get better, a practice mastered by franchises like Tampa Bay.

It seems likely that Showalter’s implementation of front-office recommendations will be collaborative, as it is in Cleveland with Terry Francona, who will sometimes ask for time in affecting a change, to identify the smoothest path in presenting the players with the new information, or alteration.

This is a reasonable request coming from a manager with 20 years’ experience in the big leagues, like Showalter. It would probably be more difficult for a rookie manager to push back, to meld.

Espada and Quatraro are so highly regarded that it’s probably inevitable that each will manage in the majors. But in this moment, Cohen recognized the artifact of managerial history he had, no matter the alternatives, cost be damned.